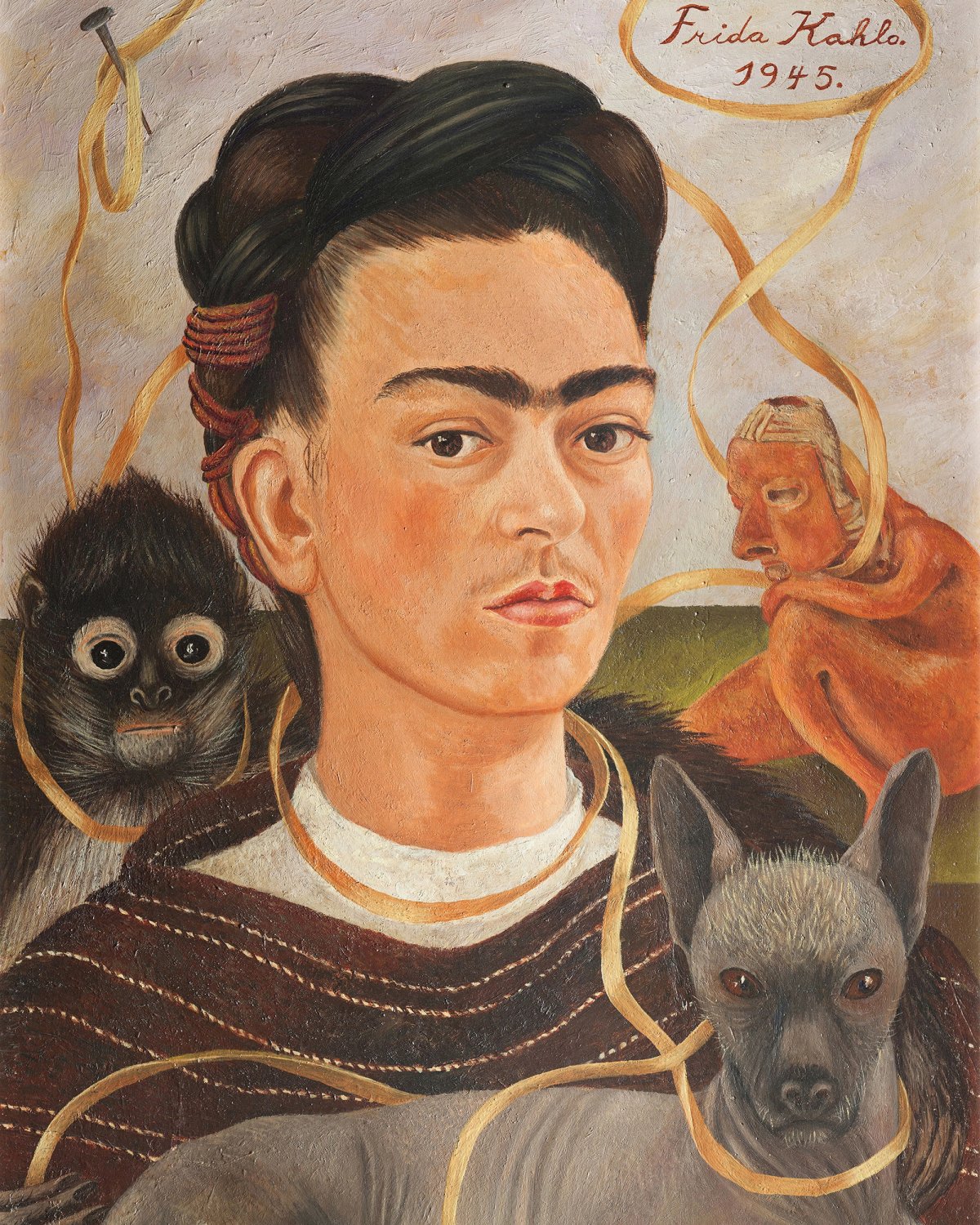

Like many institutions, the Cleve Carney Museum of Art at the College of DuPage in Glen Ellyn, Illinois—a suburb west of Chicago—had to rework its exhibition calendar when the pandemic hit. Most importantly, its landmark exhibition Frida Kahlo 2020, featuring 26 paintings and works on paper on loan from the Museo Dolores Olmedo in Mexico City and originally scheduled for last June, was postponed for a year and renamed Frida Kahlo: Timeless. Now, leading up to the new opening planned for this June—health precautions permitting—the museum is hosting a rich schedule of virtual programming starting in February.

“These were all speakers and events we had planned to coincide with the exhibition,” says the museum's director and curator Justin Witte. Rather than reschedule the talks, Witte and his colleague Diana Martinez, the director of the college's McAninch Arts Center, which co-organised the show, decided to move forward. “We can’t be static and we can’t stand still,” Witte says. An added benefit of going online is that the programme can now reach a much larger and broader audience. “It has also provided community,” Witte adds, for scholars and admirers of Kahlo’s work.

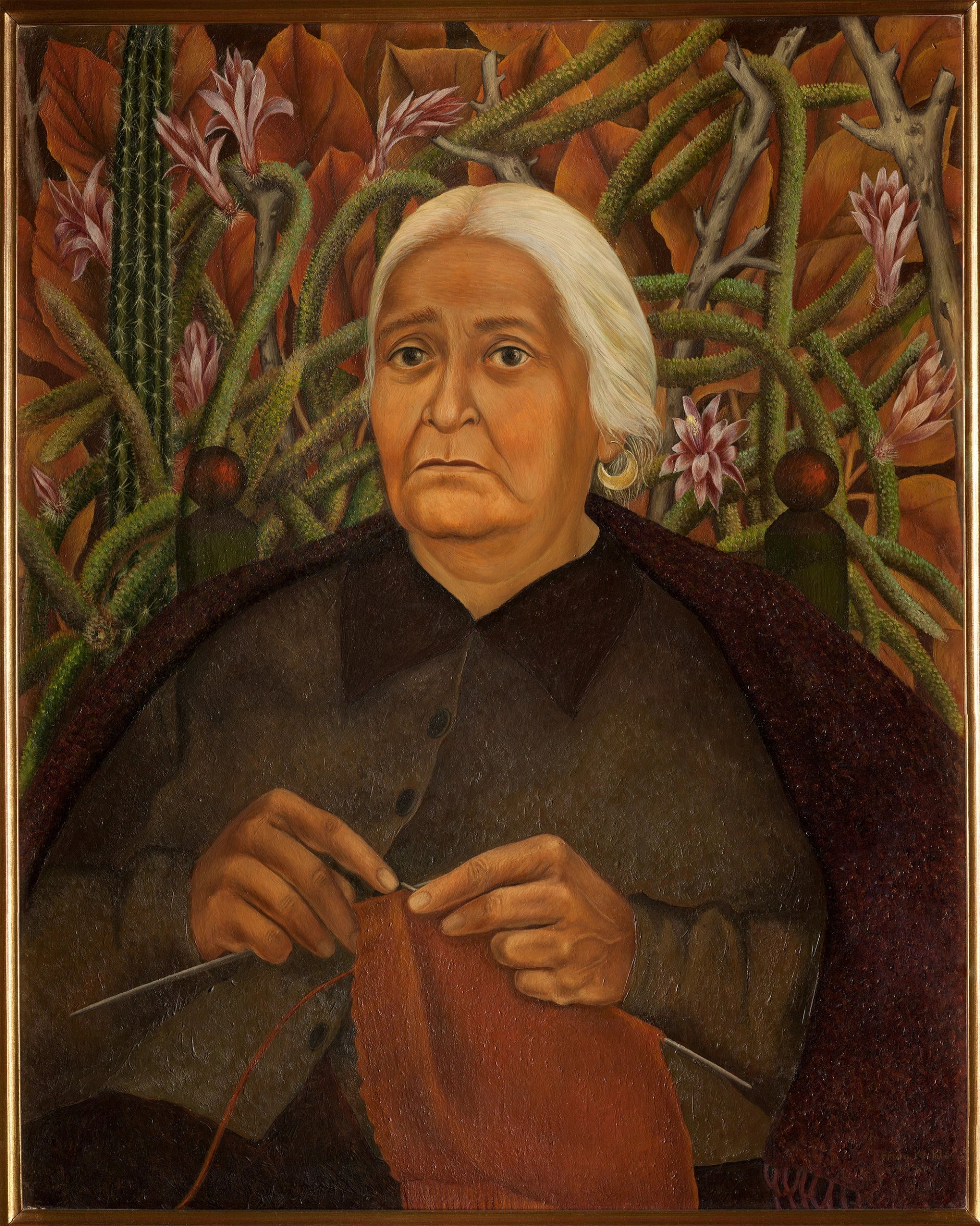

Frida Kahlo, Portrait of Doña Rosita Morillo (1944), oil on masonite Collection Museo Dolores Olmedo, Xochimilco, Mexico © 2020 Banco de México Diego Rivera Frida Kahlo Museums Trust, Mexico, D.F. / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Included in the event lineup are art historian Adriana Zavalla, who curated the Frida exhibition at the New York Botanical Garden in 2015, and the Mexico City based writer and historian Karen Cordero. Julie Rodrigues Widholm, the director of the Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive in California, will present a talk on February 21, “Contemporary Art after Frida Kahlo,” that is based on an exhibition she curated at the MCA Chicago in 2014 titled "Unbound: Contemporary Art after Frida Kahlo."

Widholm’s goal for that exhibition was to reframe the narrative around Kahlo's work and focus on the radical nature of her paintings. Kahlo’s own image had become so hyper-commercialised at that point, Wildhom says, that she felt it had caused many curators and art historians to dismiss the work. “One of the world's most famous artists is a queer Mexican disabled woman and we need to let that sink in and not gloss over it,” she says.

Frida Kahlo, The Broken Column (1944), oil on canvas Collection Museo Dolores Olmedo, Xochimilco, Mexico © 2020 Banco de México Diego Rivera Frida Kahlo Museums Trust, Mexico, D.F. / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

“It's been interesting to witness such a shift since the MCA show with a huge proliferation of exhibitions about aspects of Kahlo's life and work,” Widholm adds. “What makes the College of DuPage show so wonderful is the sheer number of her paintings that are included that are rarely seen in the US.”

The loan was made possible by the personal connection of the museum’s donor Alan Peterson to the Olmedo family, a boon that no doubt helped when it came to rescheduling the exhibition. Moving the date ahead one year also allowed the museum, which underwent a 1,000sq ft expansion ahead of the show, to create a new layout to accommodate for social distancing and traffic flow. “I had time to sit with it and think about how we can present these ideas better,” Witte says.

In the early days of planning, Witte and his colleagues were struck with the relevance of the societal themes in Kahlo’s work, “whether dealing with illness, disability, sexual identity, a turbulent political period,” said Witte. “We had no idea how far it would go.” Now with the added context of the pandemic, Kahlo’s health issues and ensuing periods of isolation is a reality that many people today are experiencing. No matter the difficulties that Kahlo faced—and there were plenty, Witte points out—“she rose above it”.