In the final episode of A brush with..., we sat down with the US artist Rashid Johnson to speak about his cultural experiences and their effect on his life and work. Johnson shares his admiration of Richard Tuttle and Parliament-Funkadelic and discusses how sobriety helped him to complete a recent series of work on anxiety and toxic masculinity.

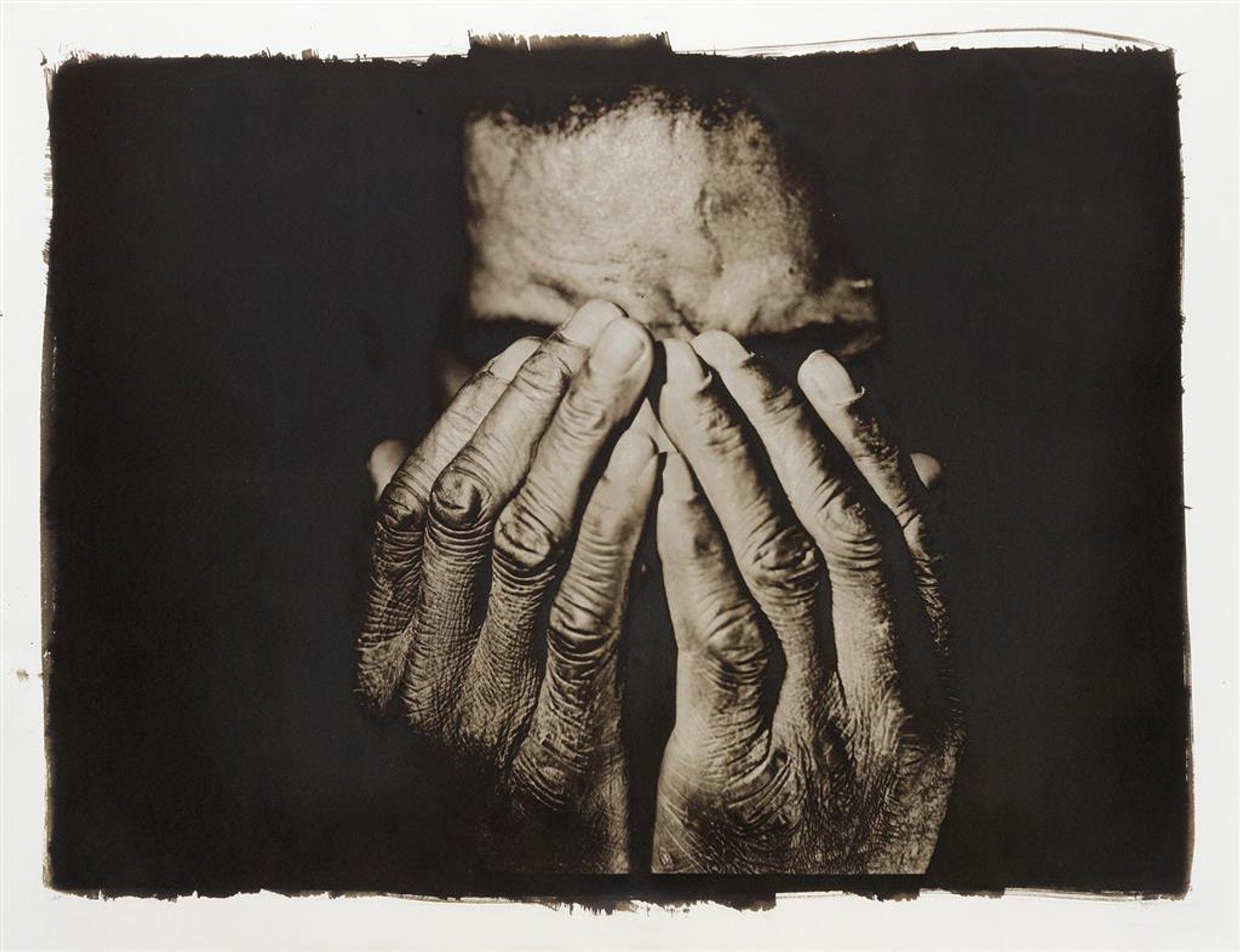

Born in Illinois, Johnson makes paintings amid a much broader range of media, having studied photography at Columbia College in Chicago before later moving to the Art Institute of Chicago. Johnson first rose to prominence aged just 24 when he showed a series of photographs of African American homeless people using techniques that evoked the grandeur of 19th-century photographic portraiture.

“Jonathan with Hands” (1997) by Rashid Johnson © Rashid Johnson

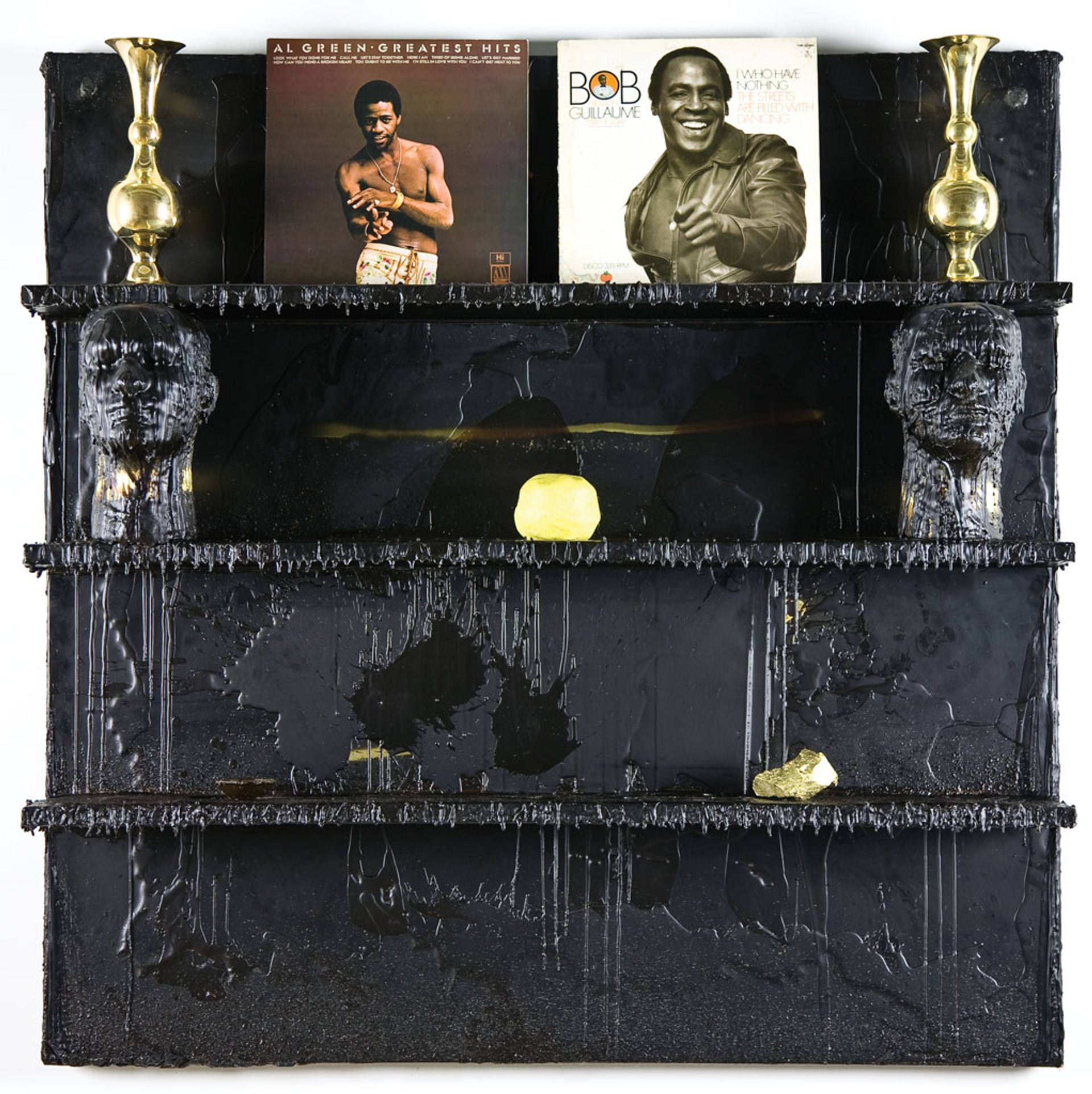

Since then, he has moved from installation to sculpture, and indeed to painting, all the time reflecting his deeply subjective response to the world alongside the cultural and social experiences of the wider Black community. Both sets of experiences are also writ large in the materials that he uses, such as paint made from black soap and wax and sculpture formed from shea butter—all of which are intimately connected with the Black body.

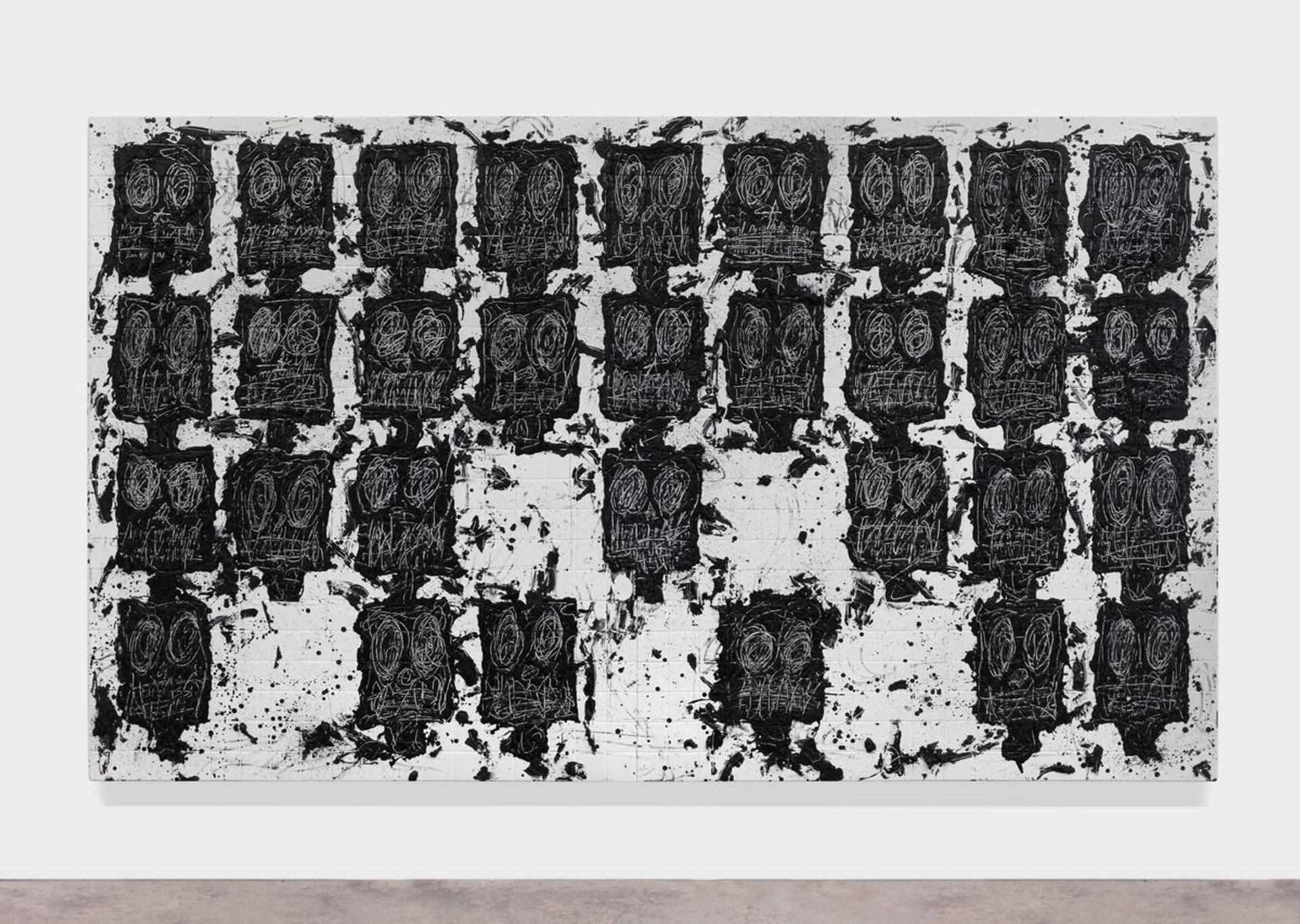

Among the most powerful bodies of work that Johnson has created in recent years is a series called Anxious Men, which he began in 2015. The series, which he initially termed a "self-portrait", evolved into paintings of groups of tormented and anguished figures that examine the fractured—and often toxic—state of contemporary masculinity. Frequently using spray paint and oil sticks on varied surfaces which include ceramic and mirrored tiles, Johnson constantly pushes the territory of painting into new and unexpected directions. A solo show, Rashid Johnson: Waves, opens across both of Hauser & Wirth's London galleries on 6 October and runs until 23 December 2020.

A brush with... comes out every Wednesday in the month of August. You can download and subscribe to the podcast here. This episode is sponsored by Cork Street Galleries.

Richard Tuttle's Tenth Cloth Octagonal (1967) Art Institute of Chicago

Rashid Johnson on... Richard Tuttle

"I often tell a story about being at the Art Institute of Chicago and coming across a work of the artist Richard Tuttle, which was a piece of cloth that was just pinned to the wall in a few different spots. I was maybe 19 at the time, and I thought to myself: 'My God, I did not know this was an option.' [...] I think some people would come to a work like that at a young age and say, 'this is not good. I am a skilled practitioner, I have higher expectations'. I came to it and was like 'this is genius'. I love it. I love the questions that it asks."

Detail of Rashid Johnson’s Monument, 2018. Rashid Johnson. Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth.

... using books in his work

"I grew up with my mother having a pretty extensive library in the basement. I remember just looking at the library [...] I love that the books are our delivery systems, but I also just love the objectness of them. I often use them in multiplicity. I will include 100 copies of the same book in one work. And in that sense, it's an opportunity to say, 'no, I didn't find this'. I'm not interested in the found object. I'm interested in the searched-for object. It performs the role of creating intentionality. Here's this book 100 times I meant for this book to be here."

Rashid Johnson, ‘Untitled Anxious Audience’, 2016. © Rashid Johnson. Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth.

... "bearing witness"

"'Bearing witness' to something is somehow more active than just standing in front of it and looking [...] our expectation for witnessing is higher than it is for looking because witnesses are expected to recall. We're supposed to be able to go to a witness and say, 'what is it that you saw?' and have them describe it to us. So I like to think of myself as a witness when I go see an exhibition in any space. It's how I often talk to my son when we go see exhibitions. Now he's eight years old and still struggles to have the patience, but I make him consciously bear witness, I say: 'What did you see? What was it? And what did it make you feel?'"

Rashid Johnson I Who Have Nothing, (2008), made from wax, soap and shea butter © Rashid Johnson

... how we're taught to approach art

"Something that we have planted in young folks is this expectation that everything that you see has some sort of meaning that you're not seeing; that there's always some sort of iconography or metaphor, that the artist has some sort of hidden agenda which you have to somehow discover or imagine that you're not privy to. I think that's dangerous, because it makes people feel like they don't understand what it is they're looking at. And a lot of times they do. You have the sophistication. You don't need a tremendous amount of antecedent knowledge to come to an art object, bear witness, explore it, and then say what that object is and how it performs in the world and feel confidence in that description. And I think that people need to feel that kind of agency."

Rashid Johnson's The Ritual (2015) Rashid Johnson. Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth.

...Sun Ra and Afrofuturism

"I listened to Sun Ra quite often and I love the message, some aspects of it I like more than when I was a little bit younger. The escapist aspects of his work are some of the things that continue to be really present in my work. Sun Ra believed himself to actually be from Mars. He had become, for whatever reason, so disillusioned by the world that we inhabit here and its limitations that he created a parallel universe for himself. That Afrofuturist narrative is conceptually fascinating to me."

Rashid Johnson's Untitled Anxious Red Drawing (2020) © Rashid Johnson. Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth.

... his use of "anxious red"

"The antecedent that I use is the work of Felix Gonzalez-Torres, which was born of a conversation around the Aids crisis. But it is also the kind of work that is able to embrace any kind of critical moment [...] I happened to have a body of work that I thought [had the potential to be] as nimble as that [...] but I needed to make a small change. And that change in this particular body of work, Anxious Men, was to give it a colour that spoke to the urgency that I thought we are all facing. And that was red."

Rashid Johnson's The Broken Five (2018) Rashid Johnson. Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth.

... Broken Men and getting sober

"I had gotten sober in 2014 and I started making [the Broken Men series] in 2015 as a response to living in a world that I didn't know how to live in without drugs and alcohol. That was paralleled by the killing of Mike Brown, Donald Trump running for president and the global refugee crisis [...] I felt like my eyes had just opened [...] A lot of my work is dealing with historical narratives and the autobiographic: What's my story? How does it fit into these historical narratives? I was making a project that was quite timeless in a sense. But the work, upon me becoming sober, started to look at the world that we were living in at the time. It was really kind of a shock. There was no more buffer. I had no escape tool, I didn't have the fluid that I had used to perform my escape. And so the work started showing a different urgency by speaking to time in a way that it hadn't so much prior. "