“I can’t think why people have previously been satisfied with inferior pictures,” Margaret Thatcher wrote from Downing Street in 1981. On the eve of the royal wedding of Prince Charles to Diana, the prime minister wanted something better on the walls to impress foreign dignitaries who would be visiting London. She had taken a dislike to the fusty decoration at Number 10, describing one room as resembling “a down-at-heel Pall Mall club, with heavy and worn leather furniture”.

Thatcher’s particular concern was the state dining room, designed by John Soane in 1827, with oak panelling and a high vaulted ceiling. She wanted “British heroes who had contributed to its greatness”, recalls Wendy Baron, the director of the Government Art Collection at the time.

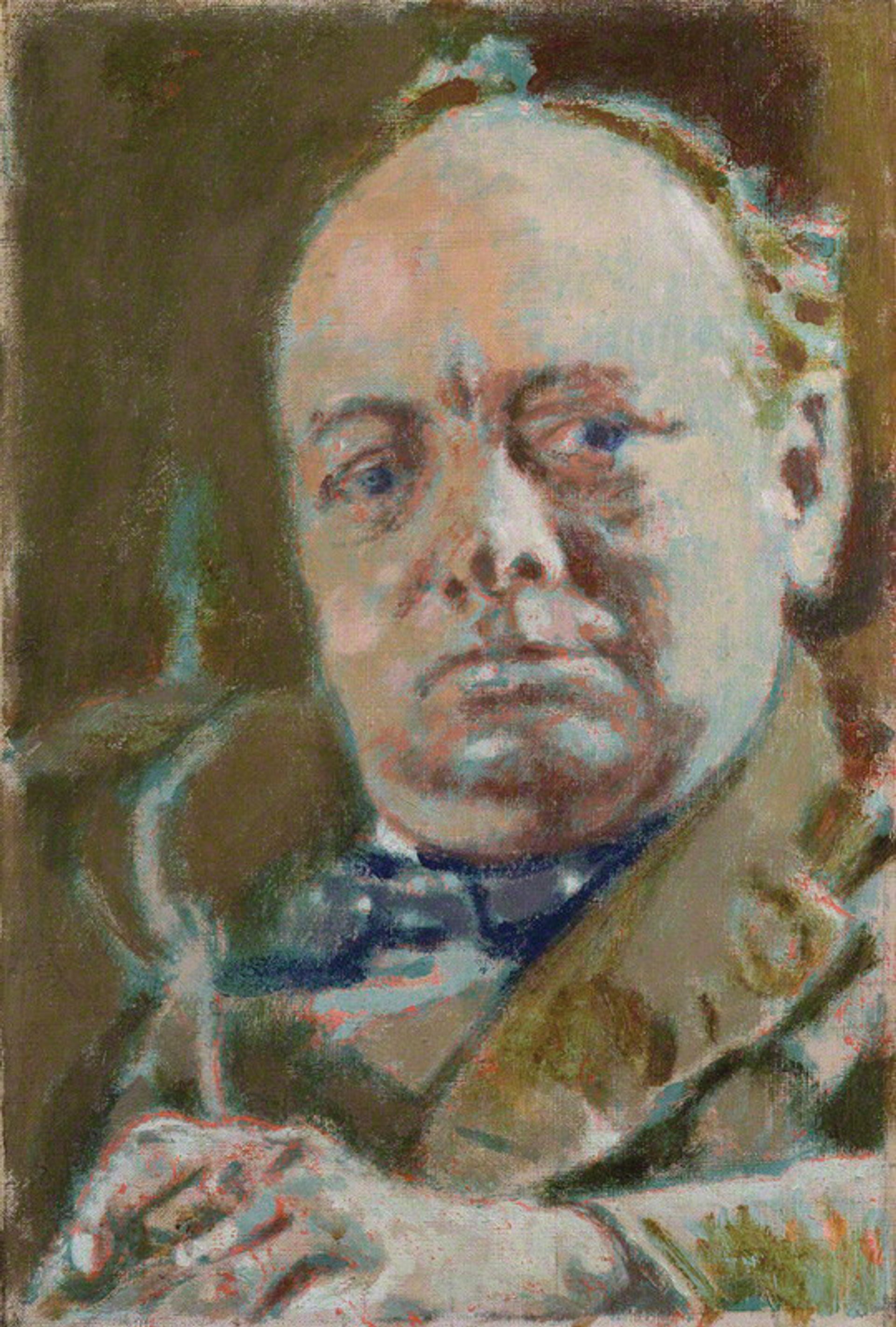

Thatcher initially wanted to borrow Walter Sickert’s depiction of Churchill with his cigar, calling the portrait in the National Portrait Gallery “marvellous”. It was done in 1927 when Sickert was teaching Churchill how to paint. But although a great admirer of Churchill, she ultimately decided that the Sickert “was not stylistically appropriate” for the room.

She expounded her forthright views in a letter to James Hanson, a wealthy friend dubbed “Lord Moneybags” by the press. The letter, dated 8 July 1981, is among Thatcher’s papers at the Churchill Archives Centre in Cambridge, which went online in June. Hanson had no formal role in advising the prime minister, and no art historical qualifications, but the swashbuckling entrepreneur was a key confidant.

When Thatcher arrived in Downing Street in May 1979, she had found the dining room decorated with four 1910 copies of late 18th- and early 19th-century portraits: of William Pitt (after John Hoppner), Nelson (after Hoppner), Wellington (after Thomas Lawrence), and Charles Fox by Walter Urwick (after Reynolds). Number 10 official R.H. Stone described them in a memo as “very inadequate paintings... rather poor copies”.

Thatcher first appealed to national museums for loans, but initially did not receive much in the way of offers. The National Gallery, the National Portrait Gallery and the Tate, said Stone, “professed themselves unable to help”.

The Victoria and Albert Museum proved more responsive, although with advice rather than loans. Roy Strong, its director, recommended introducing mirrors to the dining room, “as a means of bringing the room to life by reflecting, as they will, the light, silver and glass”. The government’s Property Services Agency offered two elegant tall mirrors, which Thatcher said “will be in keeping with the panelling and should look well on the long wall facing the windows”.

Nelson meets Wellington Thatcher, with her usual decisive approach, said: “For the central position over the mantelpiece I want to hang the Shackleton portrait of King George II in the Government Art Collection, because he was the sovereign who first presented Number 10 to the First Lord of the Treasury.”

She chose a “magnificent” William Beechey portrait of Nelson (1800), which belonged to the London-based dealer Hugh Leggatt. The picture was then on loan to the National Portrait Gallery, but it was agreed that it could go to Number 10. Leggatt often joked that he would withdraw the loan if the prime minister of the day ever did something he disapproved of.

Thatcher also borrowed an oil sketch of the Duke of Wellington; the records suggest that this was probably by David Wilkie. This loan came from the Fine Art Society, a London dealer. For the long wall, between the pair of mirrors, Thatcher chose James Northcote’s portrait of the admiral Thomas Graves (1801) from the Government Art Collection.

The portraits that Thatcher chose arrived in Downing Street just in time for the royal wedding a fortnight later. The pair of mirrors and Shackleton’s George II remain in the dining room, nearly 35 years (and four prime ministers) later. The other portraits she picked have gone, and are currently replaced by a single painting, Thomas Murray’s Three Naval Officers (1692-93).

Disraeli, Gladstone and Hastings rejected Margaret Thatcher ruled out several works in the National Portrait Gallery for the state dining room. She described two portraits of Disraeli and Gladstone as “rather sombre” for the wood-panelled room. She considered Joshua Reynolds’s portrait of Warren Hastings (1766-68), the first Governor-General of Bengal, but concluded: “There are some difficulties about having Warren Hastings here, remembering what happened to him!” When Hastings returned from India he was impeached by the House of Commons for alleged crimes in India, although he was ultimately acquitted by the House of Lords. Another Reynolds was rejected for the more practical reason that his 1773 portrait of the Earl of Bute, prime minister a decade earlier, was a little too large.