The Warburg Institute in London is embarking on an ambitious £14.5m development to raise its profile and ward off the stark challenges posed by Brexit. “We have the opportunities—architectural, financial and intellectual—not just to preserve the Warburg as an international beacon for interdisciplinary scholarship but to give it a more public role for the future,” says its director Bill Sherman, the former head of research and collections at the Victoria and Albert Museum.

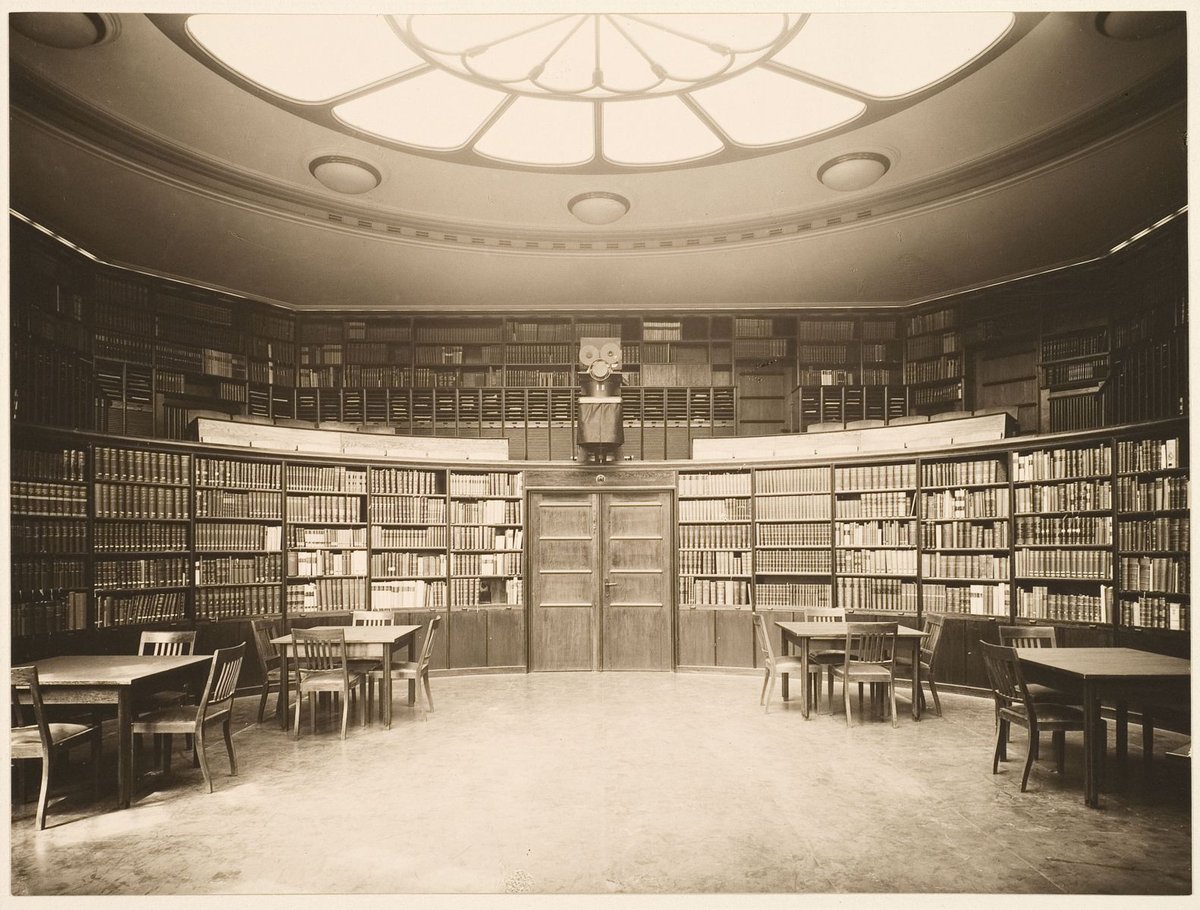

A research institute with 45 master’s and doctoral students, and 3,000 reader’s ticket holders, the Warburg is devoted to the study of cultural memory through the interactions between images and society over time. Its collection of more than 450,000 images and at least 350,000 books is based on the unique library amassed by the German Jewish art historian and banking scion Aby Warburg (1866-1929). Established in his Hamburg home in 1909, it was smuggled out of Nazi Germany to London in 1933. The institute became part of the University of London in 1944, moving into its current building, designed by Charles Holden, in 1957.

The Warburg Institute Courtesy of the Warburg Institute

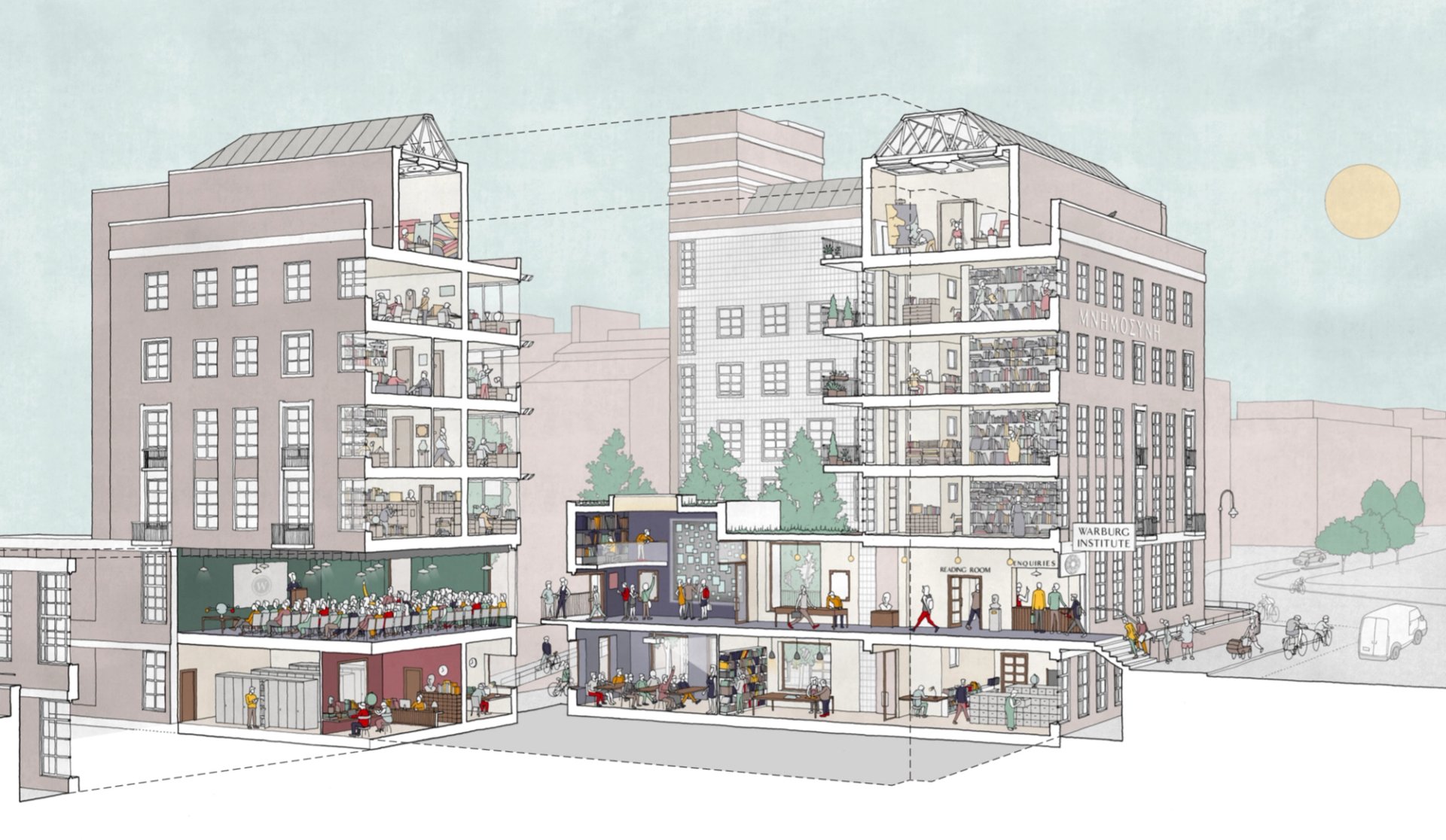

The new development by Haworth Tompkins architects, dubbed the Warburg Renaissance, is due to be completed by September 2022. Aside from expanding the institute’s research and collection spaces, the project aims to revive the original spirit of discovery and debate of Aby Warburg’s “science of culture”. Among the new public facilities planned are an exhibition gallery, a digital laboratory and a bigger lecture hall in the central courtyard, offering talks with curators, artists and scholars. The University of London is providing core funding of £9.5m, leaving £4m still to be raised.

Sherman also has hopes for a Viennese-style café, like the Neue Galerie’s Café Sabarski in New York. “The Sabarski is as close to Vienna as you get outside of Vienna,” he says. “It would be good to invoke the cafe culture of Central Europe, and these were the kinds of places where some of the best conversations happened and that generated institutes like this”.

An impression of the Haworth Tompkins-designed extension scheduled to open in 2022 Courtesy of the Warburg Institute

But the Warburg faces a significant threat from Brexit, Sherman believes. The institute risks losing vital research and student funding from the European Union (around €2m a year), from the German government, which last June pledged €6.3m over five years, and from individual donors across Europe. Sherman is also concerned that fees for European students, who currently pay the same as UK nationals, could rise by two or three times after Brexit. At present, half the student body and a third of staff come from overseas.

While Sherman pursues outreach in China, South America and the US to attract more international students beyond Europe, the institute is celebrating a major boost to the redevelopment campaign. Earlier this month, it announced a £1m lead gift from the Hamburg-based Hermann Reemtsma Stiftung and the launch of the Warburg Family Circle, attended by 26 family members from six countries. “Aby Warburg’s legacy is much more than memory,” says the foundation’s chairman, Bernhard Reemtsma. “It is vitally alive and we can still learn from his ideas. The Warburg Institute connects Warburg’s intuitive cognition to our present and future.”