In a recent report on the destruction of Uyghur cultural heritage by the Chinese state in the Xinjiang region, the Australian Strategic Policy Institute (ASPI) released some devastating numbers. Drawing on satellite imagery, data analysis and on-the-ground reporting, the think tank estimated that, since 2017, 65% of the region’s mosques and 58% of its important Islamic sites—including shrines (mazars) and cemeteries—have been either destroyed or damaged.

This is one prong of a systematic and intentional campaign of cultural erasure. It goes hand in hand with the displacement and breakup of the Uyghur nuclear family, the criminalisation of community gatherings and festivals, the disappearance en masse of academics and cultural figures, and the eradication of the Uyghur language from the public sphere. “People are putting their books into rivers,” says the photographer Lisa Ross, who has documented the region since the early 2000s. “They used to bury them, but now they’re afraid to even do that.” Observers increasingly choose to call this forced assimilation strategy a cultural genocide.

The ASPI relied on statistical sampling to gauge the extent of the destruction. China itself lists upwards of 24,000 mosques in Xinjiang, which makes confirming the status of each difficult. Many are on governmental heritage lists; the government, however, denies allegations that it is destroying its own monuments. The inventoried mosques include formal edifices, traditional structures and contemporary buildings. The latter were built, or rebuilt, in the years of relative openness and religious revival that followed the end of the Cultural Revolution in 1976. Official antagonism has intensified since Xi Jinping became China’s leader in 2012; in Kashgar alone, 70% of the mosques have been demolished since 2016. Ethnomusicologist and Uyghur specialist Rachel Harris suggests that the ASPI has underestimated the problem: she puts the number of mosques imperilled region-wide at 80%.

In his 1998 survey of the built Uyghur heritage, the French architect and anthropologist Jean-Paul Loubes noted how the culture’s ancient formal architecture combines both Persian and Mongolian influences, as evidenced particularly by the pishtaq—the symmetrical arched entrance portal framed by minarets. “We’re really in Turkic territory here,” he says, “and not at all in China.”

The Grand Mosque of Kargilik still stands but its ancillary buildings, including its impressive gatehouse, were demolished to make room for a mall CPA Media Pte Ltd

From mosque to shopping mall

Before turning mosques into shops or bars, or resorting to outright demolition, the state’s strategy has been to sinicise—to make Chinese—the buildings. Ostentatiously Islamic signifiers (minarets, domes, Arabic calligraphy) are excised. The Grand Mosque of Kargilik, built in 1540, has seen its gatehouse razed and rebuilt in miniature, with the entire site shrunk to make space for a shopping mall. The multicoloured mosaic work, which included an inscription of the Shahada (the Islamic creed) above the entrance, has given way to shoddy brickwork and blank white panels.

Kashgar’s 15th-century Id Kah Mosque, meanwhile—Xinjiang’s grandest—has lost the star-and-crescent structures that crowned its roofs, the multicoloured scriptural plaque that adorned its entrance (it was moved inside) and its congregation. The entire old city in which the mosque was ensconced was demolished, the inhabitants displaced and a vast plaza created, replete with shiny modern shops. Loubes describes this reframing of Id Kah as a prime example of the older Uyghur space being substituted with Chinese urban space.

The Id Kah plaza remains empty on Fridays, too. People no longer pray in public and the state has sent officials into family homes to root out private devotion. This divorcing of the community from the heritage it created is at the heart of Xi’s policies. The aim, an official explained on state media in 2018, is to “break [people’s] lineage, break their roots, break their connections and break their origins.”

And even more than the mosques, it is in the mazars, that this strategy is most devastating. Shrines erected at holy Islamic sites and burial grounds, the mazars memorialise historical Uyghur figures. Visiting them is as much a religious duty as a history lesson. They range from the sumptuous Afaq Khoja mausoleum in Kashgar (now museumified and inaccessible to pilgrims) to simple, unmarked mudbrick structures, to lone trees or natural springs in the Taklamakan desert.

The damage these places have sustained is multi-levelled. First, in outlawing all group gatherings, the state attacked the communities that keep them alive. Pilgrims would bathe in their sands and swallow fragments of mortar from their walls, believing in their healing powers. They would hang handmade flags from mounds of wooden poles at the foot of the tombs—ephemeral installations that bore witness, says the historian Rian Thum, “to how many other people share your belief that this place is powerful”. Yet the mazar closures, beginning in 1997 with the shutdown of the 10th-century Ordam Padishah, led to the end of all shrine festivals throughout Xinjiang by 2015.

Then there are the more recent material losses. The mazar honouring Imam Je’firi Sadiq, near Niya, has been demolished, as has the entire complex of Ordam. Of Imam Asim, near Khotan, all that is left is the mudbrick building around the actual tomb of the saint: a mosque has been levelled, and all wooden structures destroyed. Thum keeps a checklist of others he worries about; every two weeks he checks Google Earth for changes to their appearance.

Lost treasures

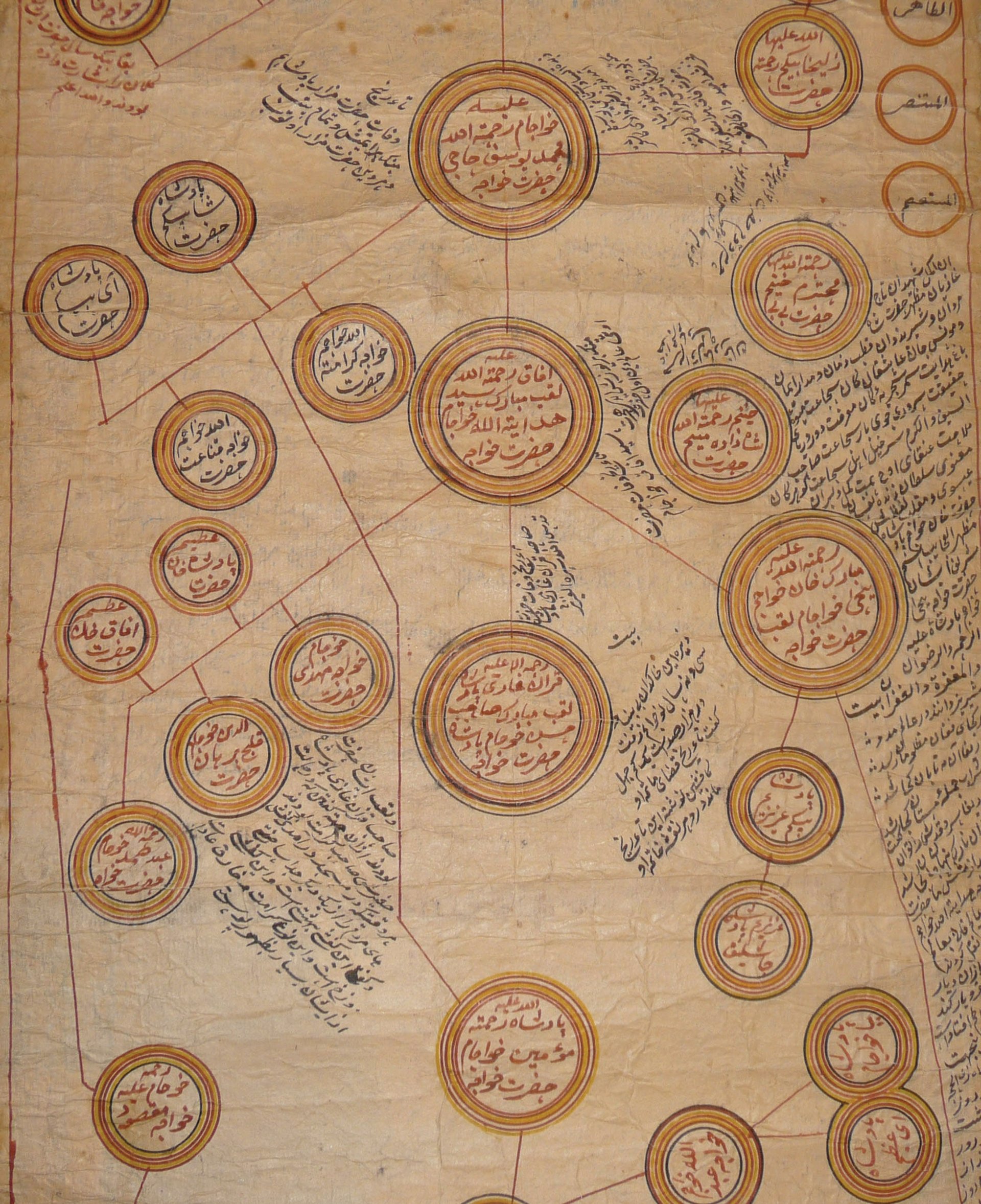

Third is the loss—feared, when not confirmed—of artefacts held within the mazar complexes: the gigantic historic cooking pots at Ordam used for communal meals for visitors; the 17th-century reliquary recorded at the Abdurakhman Wang mazar in Yarkand by Rahile Dawut, the pre-eminent Uyghur mazar specialist who disappeared in 2017. Another scholar, who spoke on condition of anonymity, supplied photographs of an 18th-century scroll from a shrine in southern Xinjiang, which featured a genealogy of Sufi leaders, including a former ruler of the Uyghur region. The status of these treasures remains unclear.

Lastly, the loss transcends the Uyghur civilisation. Aurel Stein, the Hungarian-born British archaeologist and the most famous to have studied the region, believed Imam Je’firi Sadiq and most of the desert shrines more broadly to be situated on or near pre-Islamic Buddhist holy sites. “This is important archaeological heritage that just cannot be replaced,” Thum says. “There are questions which will not be answerable anymore once they bulldoze these places.” As with the destruction of the old city of Kashgar most famously, but also of old Uyghur neighbourhoods in Khotan, Yarkand, Karghalik and Keriya, summary demolition precludes any opportunity for scholarship in a field that historically has received scant attention.

A scholar supplied The Art Newspaper with photographs of an 18th-century scroll that traces the genealogy of Sufi leaders from the Afaqi line of the Naqshbandi order, including a former ruler of the Uyghur region

Beyond the obliteration of the fabled tombs of the mazar is the loss of ordinary people’s own resting places. Aziz Isa Ëlkün, a London-based poet who grew up in the Uyghur countryside, says: “What I remember is the village mosque, the school, the graveyard. The connection to the latter is a spiritual one but, more than that, it is proof that we are the owners of that territory.”

Ëlkün’s father died in 2017, and it was in looking for his grave on Google Earth last year that he found the cemetery had been flattened (along with a reported 100 others), and the remains of his father forcibly moved. “Razing that is like killing someone’s spirit,” he says. “It is unforgivable.”