In a ruling that cited but did not impose “a just and fair solution” on a restitution dispute in court for 15 years, a three-judge panel from the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals in California said the Thyssen-Bornemisza Collection Foundation is the legal owner of a painting by Camille Pissarro that a Jewish family seeking to leave Germany under duress, handed to a Nazi official in 1939.

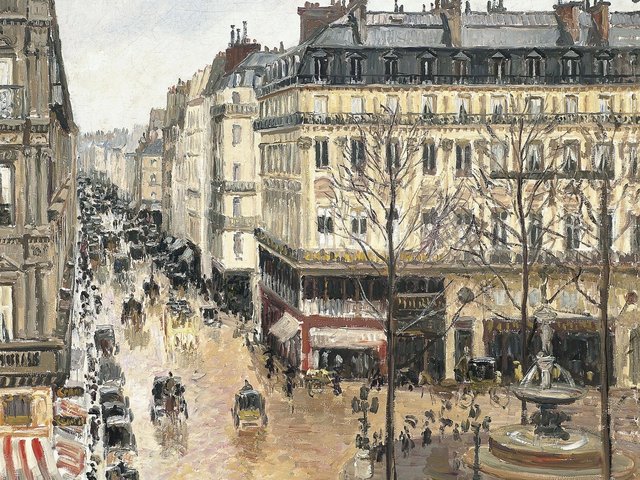

The claim on Rue Saint–Honoré, après-midi, effect de pluie (1892) was made in 2005 by Claude Cassirer, the grandson and sole heir of Lilly Cassirer Neubauer. Neubauer left the work in 1939 with a Nazi appraiser of her property, who paid around $360 into a blocked account that she could not access. Claude died in 2010, and his son, David Cassirer, has continued the suit.

Throughout the trial in California, lawyers for the Spanish foundation argued that Baron Hans-Heinrich Thyssen Bornemisza, who bought the picture from a New York dealer in 1976, did not know that it was Nazi loot. Nor, they said, was the painting’s history known to the Spanish government, which acquired the baron’s collection for the Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum in Madrid in 1993 for $350m. The collection had already been on loan in Madrid for five years.

Thaddeus Stauber, who represented the foundation, noted that the German government compensated Lilly Cassirer Neubauer for the painting at its market value in 1958. Claude found the painting at the Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum in 2000.

Stauber called the case “significant” because it proceeded through trial and appeal stages, and for the thoroughness of its provenance research. “This is the first trial on the merits, particularly involving a foreign sovereign, based on the historical record, not on a statute of limitations,” he said. His client did not dispute that the Pissarro was looted.

In the end, the court found that, under Spanish law, the foundation owned the painting.

In their ruling, however, the judges noted that Spain signed the Washington Principles of 1998 (among other agreements), in which 44 countries called for applying moral standards to Nazi-Era art disputes. Calling those principles unenforceable, the opinion states: “It is perhaps unfortunate that a country and a government can preen as moralistic in its declarations, yet not be bound by those declarations. But that is the state of the law.”

For the restitution lawyer E. Randol Schoenberg, “if there is a bright spot in the opinion, it is the recognition that Spain isn’t living up to the public image it wants to project. Like the Cranachs in the Norton Simon Museum [California], the Pissarro is a painting stolen from a Jewish family that was never returned. Period. End of story.”