The extent of the gender pay gap was exposed last month after UK companies with more than 250 employees were compelled by the government to submit pay data—and auction houses, as the largest employers in an industry where most businesses are too small to meet the reporting threshold, are now on record.

The largest divide is at Bonhams, where women earn 37% less than men. At Christie’s the gap is 25% and at Sotheby’s it is 22%. The pattern extends to bonus pay, too: at Bonhams, women’s bonuses are 44.8% less than men’s, at Christie’s the difference is 40.3%, while at Sotheby’s it is 16.7%. The median pay gap across all industries is 9.7%.

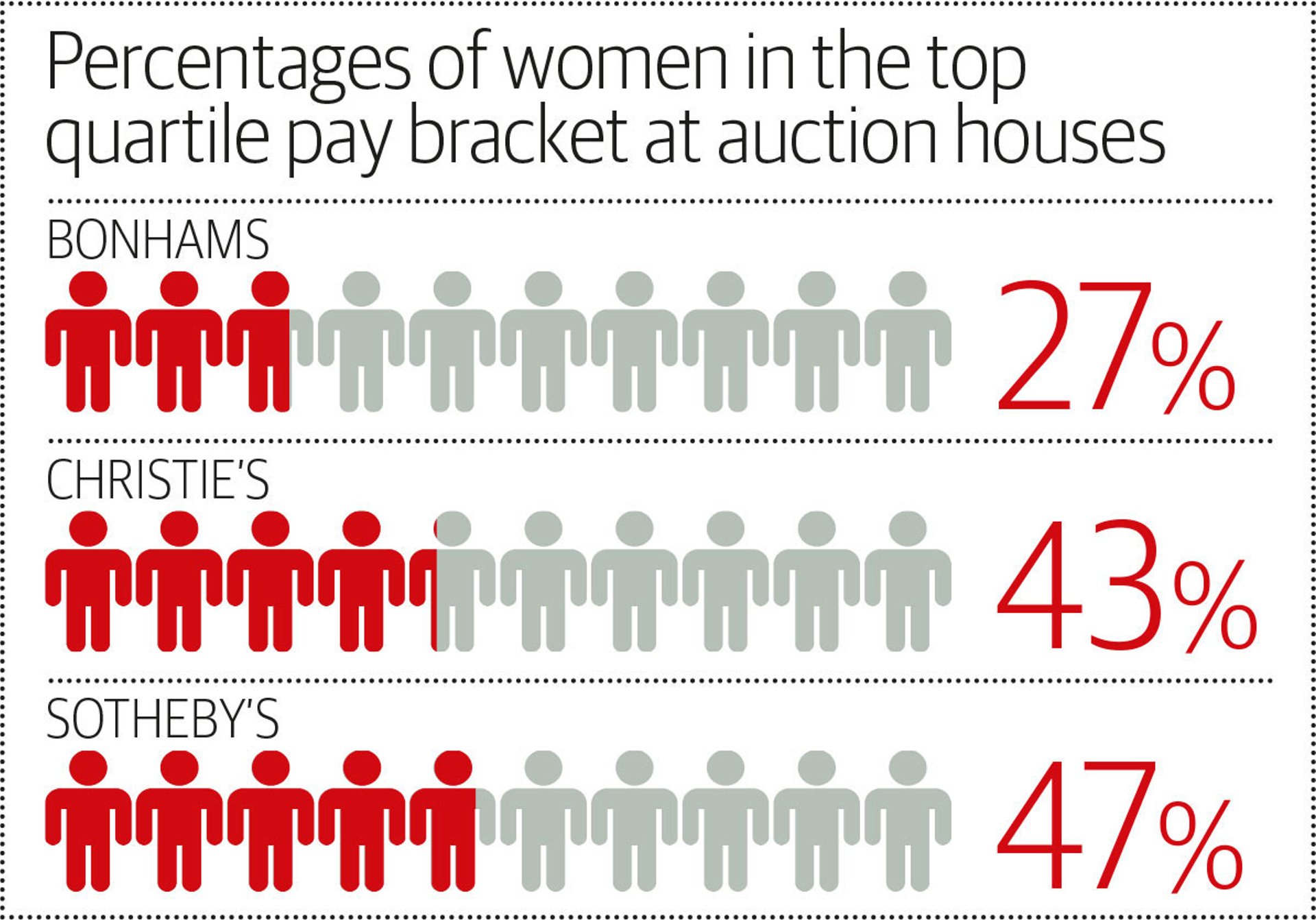

The companies must also report the proportions of top earners: at Bonhams, only 27% of the top quartile earners are women, at Sotheby’s 48% are female and at Christie’s 43%. The figures pertain only to UK operations, and are based on median hourly earnings. They include part-time workers, of which more are female than male.

There are no equivalent statistics for offices in the US or Asia, where more women hold key roles, nor would the auction houses provide a breakdown of their top 10% of earners, but women are also a minority at board level. At Bonhams, three of its 15-strong international board are women; Christie’s executive management group of 16 people includes five women; Sotheby’s executive leadership team consists of 10 women and 13 men. The exception is Phillips, which has an executive committee comprising nine members, five of whom are female. (As a smaller organisation, it is exempt from gender pay gap reporting requirements).

Lucinda Bredin, Bonhams’ global director of communications, says: “We fully recognise that we have work to do to address this issue, which is a reflection of the fact that Bonhams has more men than women in the senior, more highly remunerated roles.” All of the auction house’s high-earning automobile specialists are men, which could throw the overall figures. Bredin adds the company is establishing a “task force to look at ways of ensuring that more women have the opportunity to move into these senior positions. This will cover mentoring, career path transparency and work-life balance.”

A spokeswoman for Sotheby’s says that, while its statistics are “skewed by the fact there are more women in junior and administrative roles”, Sotheby’s “is committed to addressing the issue”.

‘A reflection of the past’

Guillaume Cerutti, the chief executive of Christie’s, says the imbalance at the top of the firm “is a reflection of the company’s past”, but stresses he is taking steps to redress the imbalance. Within two years, he aims for Christie’s executive management group to be an even split.

However, for many employees, past and present, the figures are illustrative of a culture of sexism that dates back decades. Some say historic pay inequalities—different from the gender pay gap, when men and women in the same roles are paid different amounts—have been just as harmful. Rachel Kaminsky, who joined Christie’s New York as a secretary in 1983 aged 22, and rose through the ranks to become the first female Old Master head of department in the firm’s history, recalls a climate where women were “simply treated differently”.

After her senior director and mentor Ian Kennedy left Christie’s in 1993, Kaminsky continued to manage the Old Master department on her own. “I had been head of Old Masters for almost five years and had been running the department on my own for about a year. We were doing very well, as proven by the results,” she says. “But [previously] my department was run from London and they were not keen on a woman department head, Old Masters being an almost exclusively male field.”

Kaminsky says she agreed to train a new senior director “with zero art market experience” on condition she was promoted to senior vice-president, on a par with two male colleagues of a similar age and seniority. She was not given the promotion, but she was offered a pay rise in line with the two men. “I knew then for a fact they were making around 35% more than me,” she says.

The situation nearly came to a head in the 1990s when, according to one former employee, several female department heads at one auction house considered legal action, at a time when some firms forbade women from wearing trousers. “[But] everyone was basically told the same thing: discrimination is very hard to prove, and do you plan to continue working in this industry?” she says.

There are some more recent allegations of pay inequality. One woman, who worked as a cataloguer in the paintings department at Bonhams between 2005 and 2011, left shortly after learning that two male colleagues were being paid 25% more than her £18,500 salary: “Like me, they had each started their careers at Bonhams, had the same job titles, but had joined after me and spent less time in their comparable roles.” However, when she appealed to management, she was told that the two men worked in different departments to her. She says she lacked the confidence and funds to take matters further, so decided to leave the company.

In response, Bredin says: “Bonhams has always been an equal opportunities employer. As in most organisations, our salaries are structured in bands, within which we pay individuals–whoever they are–according to experience, levels of responsibility, personal performance and the needs of the business in a competitive jobs market. The one factor that plays no part at all in this is gender, and it is quite wrong to suggest otherwise.

Ongoing effects

Maternity benefits and childcare are other areas where auction houses have historically lagged behind. “Ten years ago, in the UK, we were losing 55% of women after their first child and around 70% after their second,” says Catherine Manson, the global head of communications and corporate affairs at Christie’s. The firm established a taskforce to improve employee retention, and Manson says the percentage of women not returning after childbirth has now dropped to single digits. “We have become a much more family-friendly company in the past ten years,” she says.

While things have improved, with pensions linked to earned income, the past will have an effect for years to come. As one employee who left the auction business in the 1980s noted: “This is the gift that keeps on giving. When we women get our pension and Social Security cheques, we will once again be receiving less than our male counterparts.”

Percentages of women in the top quartile pay bracket at auction houses

The Art Newspaper