“Hollywood is a place where they pay you a thousand dollars for a kiss and 50 cents for your soul,” Marilyn Monroe once said. As Frieze launches its first Los Angeles edition, many dealers in the city are weighing up whether the fair group is puckering up or selling out.

For its third location, adding to London and New York, the fair’s trademark white tents will blanket the Paramount Studios compound from 15 to 17 February in an attempt to woo the city’s long misunderstood art market. It will not be easy; other LA fairs have routinely flopped in the past. Yet the clout of the fair’s invitation-only roster of 68 blue-chip exhibitors and star-studded host committee—including the actors Tobey Maguire and Salma Hayek, as well as Hayek’s husband, François-Henri Pinault, who sits on the board of Christie’s—have many Angeleno dealers feeling cautiously optimistic about the future of an LA-based fair.

“We’re not interested in supporting fairs; we’re only interested in fairs that support us,” says Peter Goulds, the founding director of the inveterate Venice Beach gallery, LA Louver, which opened in 1975. Gould says the gallery has participated in only 29 fairs in 44 years—none of them Frieze events. Nevertheless, he sees the British fair group’s arrival on the LA scene as timely.

“London was stimulating in the 1970s-80s because there were a lot of under-recognised artists there,” Goulds says. “Then it was New York in the 90s and 2000s. Now the critical mass is here, not just in terms of artists but young museums still building their collections and new collectors moving into the area.”

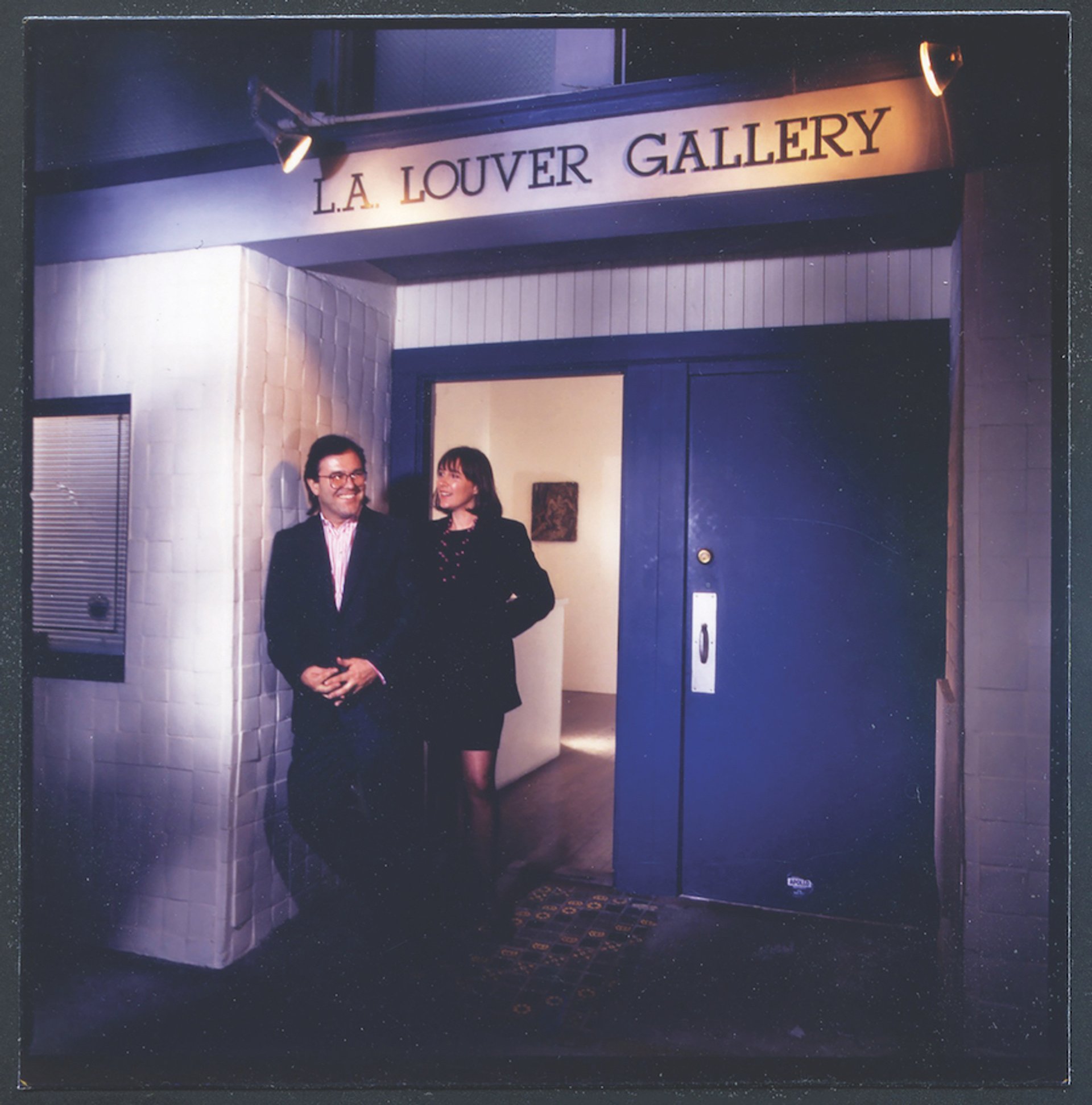

Veteran LA dealer Peter Goulds (pictured in 1983) has never exhibited with Frieze before Photo by Shelley Gazin and courtesy of LA Louver

Whether the market has grown enough to accommodate a fair of Frieze’s stature is one of the most pressing questions facing the launch of the LA edition. “Other fairs here have struggled to gain national and international attention because they could not attract enough galleries of international stature. And the local audience, the West Coast, hasn’t been big enough to attract the galleries and outside collectors required for a successful venture,” says Michael Kohn of Hollywood’s Kohn Gallery, which, despite participating in London and New York editions of Frieze over the years, is not doing the inaugural LA version.

Although Kurt Mueller, a director at David Kordansky Gallery, which has taken part in numerous Frieze fairs since 2006, says the expansion of the local market since the gallery opened in 2003 is “significant”, thanks in part to digital technology and communication. “Los Angeles, which used to be an edge, a periphery of the US art world, plays a more central role [now],” he says. “Especially in regard to Asia, the city has the potential to be a hub and crossroads.”

Whether Asian collectors will make the journey, especially in light of recent economic downturns, remains to be seen. Indeed, one of the largest drawbacks of an LA-based fair has been its lack of geographic proximity to other art-world nexuses—it takes more than 12 hours to fly in from both Asia and Europe. The city’s sprawling landscape and heavy traffic are also problematic.

“LA provides a certain set of challenges to an international art fair, the biggest one being the spread-out nature of the city and the difficulty to get from one place to another,” says Susanne Vielmetter, a long-time Frieze exhibitor, who started her eponymous Culver City gallery 30 years ago. “Simply managing traffic and parking [have been] the most difficult aspects over which past fairs have failed.”

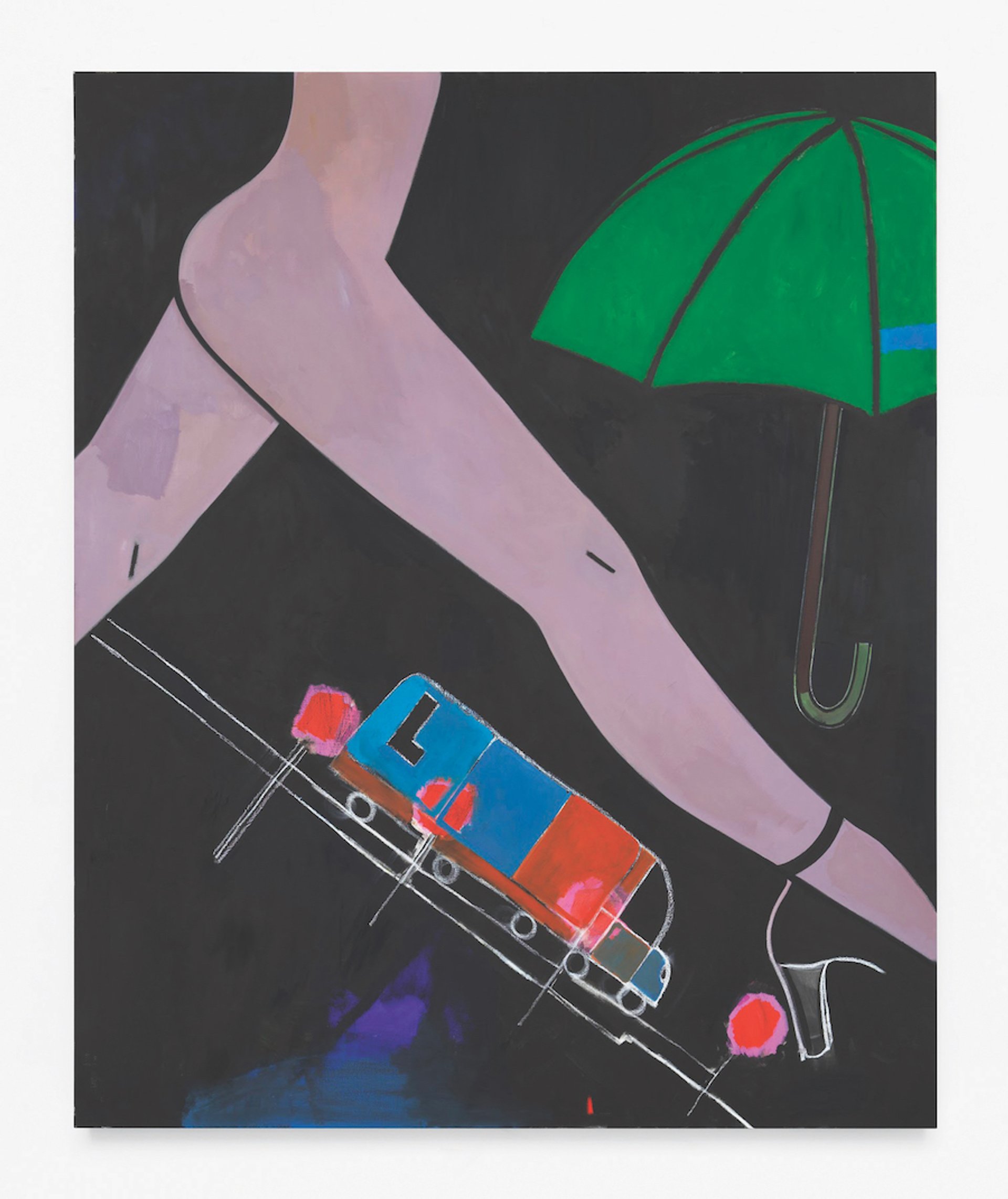

Susanne Vielmetter Gallery has participated in Frieze regularly and will show work by Ellen Berkenblit for the first LA edition Photo by Matt Grubb

Indeed, other international fairs that have attempted to tap into Tinseltown’s collector base, such as Fiac Los Angeles and Paris Photo LA, fizzled out faster than an on-set celebrity romance, while homegrown fairs such as Art Los Angeles Contemporary and the LA Art Show struggle to attract attention. Frieze, too, has had its own recent setbacks, including lacklustre New York editions and the long shadow cast by the revelation that the Hollywood entertainment group Endeavor, a major shareholder, is attempting to get out of a $400m Saudi investment following the murder of the journalist Jamal Khashoggi.

These factors are not overly concerning, according to Mueller. “Frieze is not just a fair, but a brand with marketing know-how, presence and reach,” he says. It has the potential to galvanise popular local interest and desire—otherwise committed to other forms of culture, entertainment and commerce—for contemporary art.”

Maggie Kayne of the neighbouring Mid-Wilshire gallery Kayne Griffin Corcoran thinks that, compared to other major cities, there is more “flexibility and opportunity to think outside the box in LA”. She believes New York and London have become “prohibitive, financially and reputationally, for artists and galleries to take risks—and risk-taking is so fundamental to this business”.

Most local dealers are keeping their expectations firmly in check. With a glut of fairs cropping up globally, a dose of scepticism is healthy, especially in a city where appearance so often triumphs over substance.

“What are we defining as the metrics for success? Sales? Beloved by artists? Able to draw a crowd?” asks Alex Freedman of the Paris- and LA-based gallery Freedman Fitzpatrick. “Los Angeles is an entertainment town, with Silicon Valley closing in. Ari Emanuel [the co-chief executive of Endeavor] is a savvy man and will do his damnedest to make sure the former rallies around Frieze, while Frieze’s team will maximise its own network. The question is, will the audience acquire works from a broad enough range of galleries to breed confidence?”