As Covid-19 shuttered physical art spaces, many museums, fairs and galleries quickly focused their energies to translate art viewing onto digital platforms. Yet some artists have turned to a decidedly low-tech alternative to the internet—the US Postal Service (USPS)—engaging with the history of mail art, sharing physical artworks and creating connections, even in isolation. And, as the USPS has become a target of the Trump administration as it looks to cut federal costs, the act of mailing art in a crisis has taken on a new urgency.

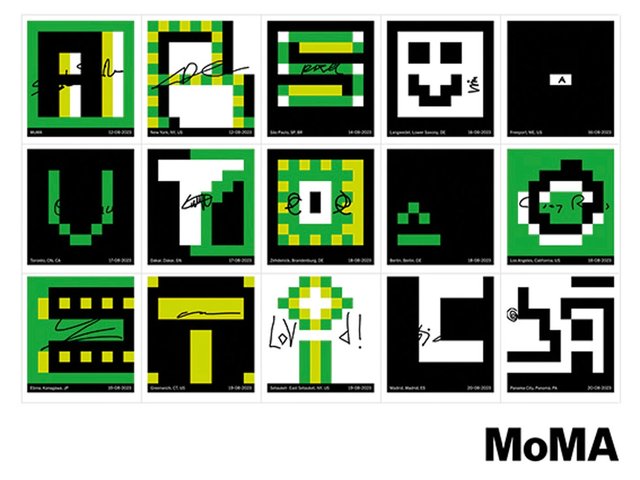

The New York-based nonprofit Printed Matter is using the USPS as a means to engage with the public via an open call for mail art submissions. “It’s an important moment to feel connected,” spokeswoman Johanna Rietveld says. “Both correspondence art and artist-run publishing aim to democratise the art world.” Printed Matter will accept submissions until 18 May and plans to produce a publication from selected contributions.

It’s an important moment to feel connected

Northern Michigan University, Marquette, US Photo by Alex Perz on Unsplash

Dream Farm Commons, an artist-run exhibition space in Oakland, California, has put out its own call for mail art. When the gallery was forced to postpone its summer exhibitions, “that felt tragic to me”, says Ann Schnake, one of the artist-founders. In response, the organisers asked communities to send art. Submissions, whether by post or dropped in the gallery’s mail slot, will be displayed in the gallery’s storefront windows, and included in a digital catalogue.

Professors have also turned to mail as a teaching tool. After the University of Idaho transitioned to digital classes, Mike Sonnichsen, an assistant professor of art and design, asked his printmaking students to create mail art and send it to “someone who might need something thoughtful and tangible” in their mailbox. “For me, there was something analogous between making prints and making mail art, which isn’t really finished until it is mailed and received by someone,” Sonnichsen explains.

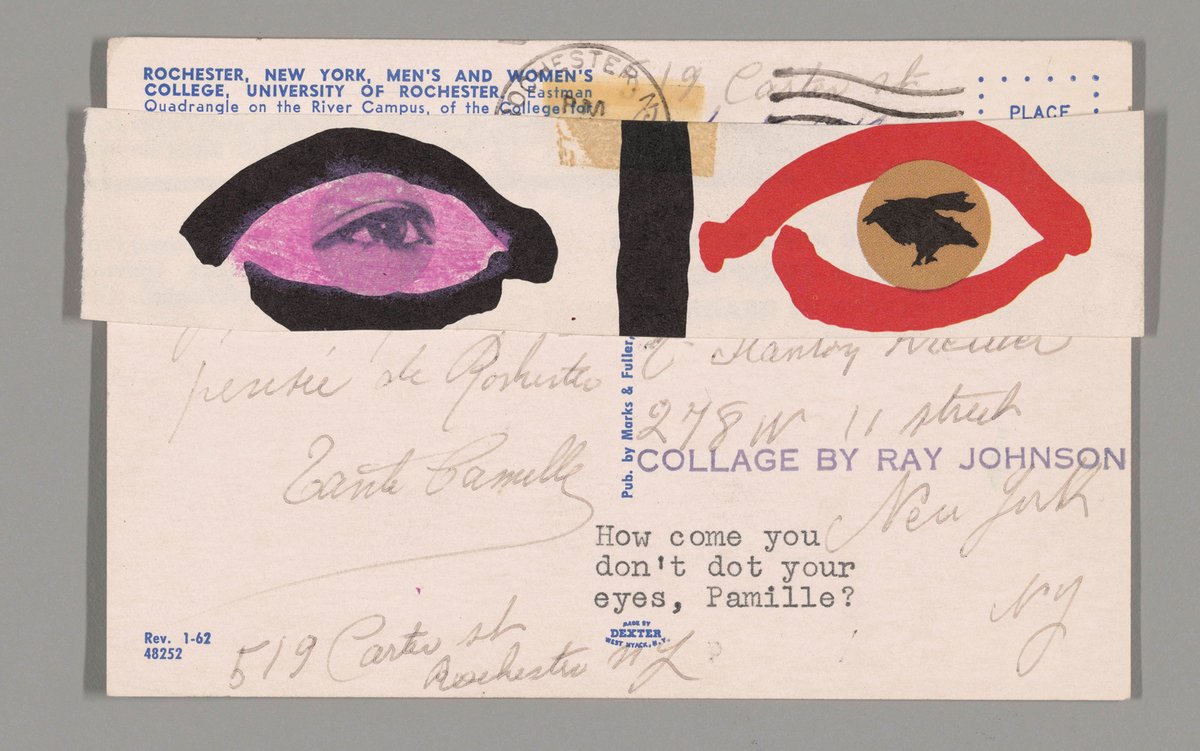

Artists have used the post as a distribution channel for decades. Chuck Welch, known to his correspondents as CrackerJack Kid, has sent art through the mail since the late 1970s, as has artist Mark Bloch. Today, both are also active historians of mail art. Correspondence art networks often trace their roots back to Ray Johnson, an artist who sent countless missives to addressees across the world and declared his activities a “school” around 1962. These postal communities merged with experiments by members of Fluxus, such as George Brecht and conceptual artists such as On Kawara. Global networks formed throughout the 1970s, allowing artists from Japan, Latin America, Europe, the US and elsewhere to exchange ideas and images well before the availability of email and social media.

Ironically, Covid-19 closures have affected numerous exhibitions celebrating these histories. Bloch curated a show of his archives at NYU’s Fales Library, slated to open 26 March and now postponed. The Brattleboro Museum and Art Center in Vermont had to shut its doors just days after the opening of a show, curated by Welch, that celebrates 40 years of mail art by Stuart Copans.

Shortened exhibition timelines also impacted a younger generation of mail artists. Mitsuko Brooks, a New York artist who started out in the 1990s zine scene, was included in an annual postcard exhibition, “Fe*Mail*Art,” at A.I.R. Gallery in Brooklyn. The gallery shut in response to Covid-19 on 13 March, two days before a scheduled closing reception and postcard sale. “Historically, those final days are a critical time for the artists,” says Nicole Kaack, the gallery’s associate director.

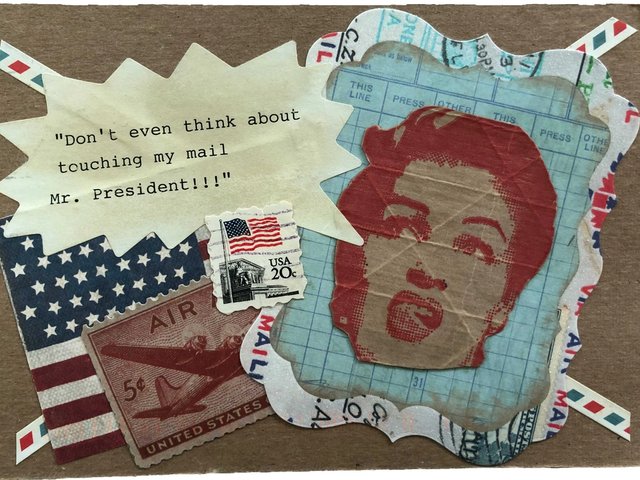

Bloch has used his exhibition’s postponement as a catalyst to crowdsource images of historical postal art, contributed on social media under the heading “Early Mail Art” by other artists. Brooks has seen increased requests for her mailed work and interest from new correspondents. “The gift of receiving an artwork that also exists as a letter during these quiet, tough times, seems all the more relevant,” Brooks says.

Indeed, the precedent of mail art has inspired other artists to experiment with it. Barbara Fisher, an artist in Asheville, North Carolina, distributed 66 small paintings on synthetic paper to artists, collectors, and friends. “I started thinking how nice it would be to send something out into this crazy world to hopefully bring some joy and mystery to people,” she says.

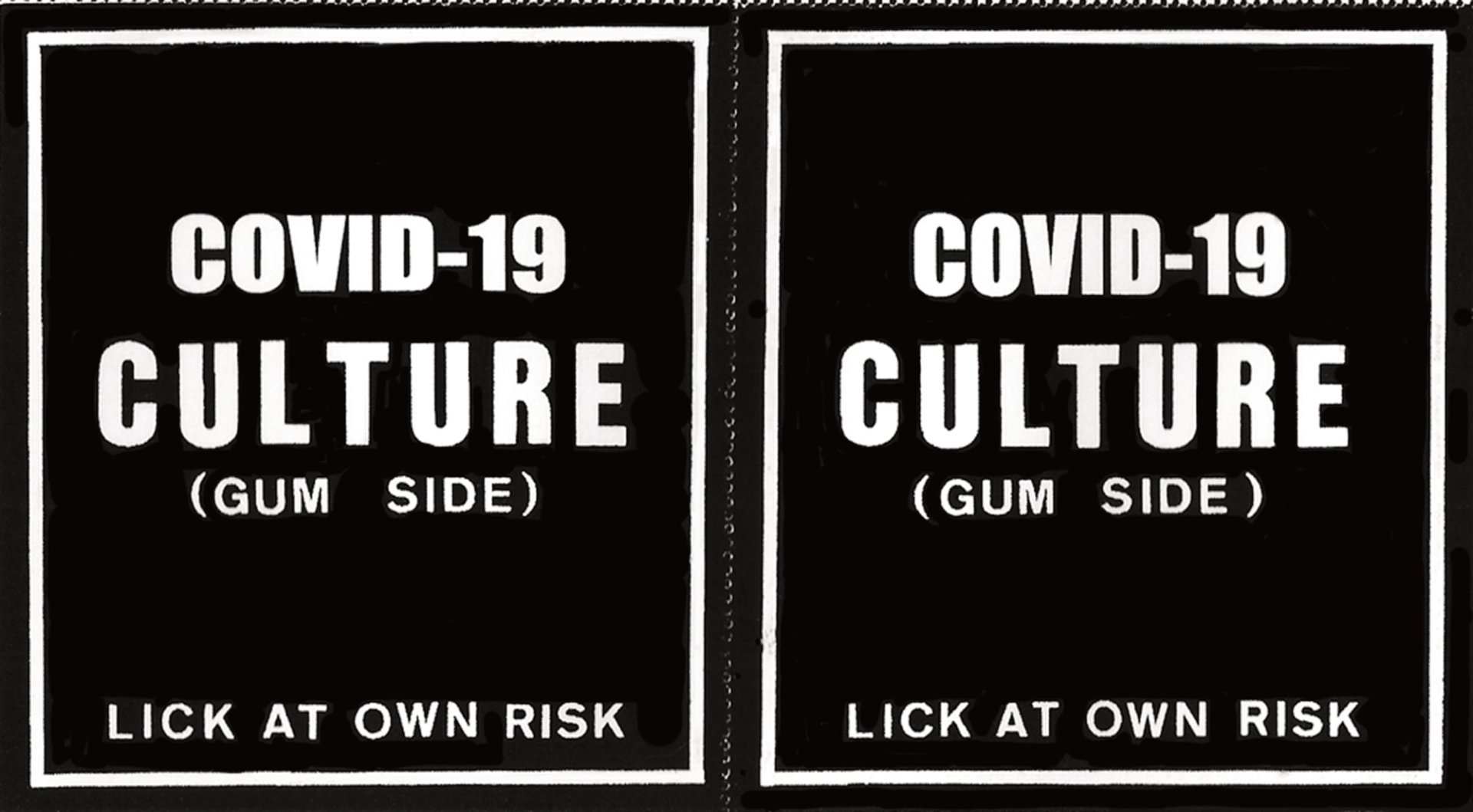

COVID-19 Test Stamps - COIL by Chuck Welch. "I created the stamps out anger and frustration when my daughter called from NYC to say she had the coronavirus and couldn't get tested," the artist says Courtesy of the artist, Chuck Welch

Handling mail during a pandemic has its drawbacks, however, something the organisers of these initiatives take seriously. For reasons of health, and of time, many of these projects also have an online presence and will accept digital submissions. “We’ve received a good amount via mail and even more via email,” Rietveld explains about Printed Matter’s project. “We wouldn’t want anybody to put themselves or their surroundings in danger by going to the postal services if they shouldn’t.”

The risks for delivery workers and services became apparent as the virus spread. The USPS has been hit particularly hard, seeing mail volumes and resulting revenues decline precipitously, even as some workers contract the virus. As Republican Senate leadership and the White House rebuff calls to include the USPS in new stimulus packages, the funding outlook for the service, active since 1775, appears uncertain.

On 13 March, the day Trump declared a national emergency, Welch created a set of black stamps that read Covid-19 Culture Fake Test, a commentary on the federal government’s inability to provide adequate tests to help control the spread of the virus. Licking the stamp tells you just as much about your health as the non-existent tests—nothing. They also highlight the intimate connection that mail art requires: the sender attaching a stamp, postal workers handling the mail, the recipient experiencing a new touch.

“What I fear is President Trump’s desire to shut down the USPS with legislation that outsources mail through commercial carriers,” Welch explains. “There is a real threat that this kind of legislation may pass if the economy doesn’t recover.”