A near forgotten exhibition that took place at the Royal Academy of Arts at the height of the Second World War in 1944 is being partially recreated at the Sala Brasil, the exhibition space of the Embassy of Brazil. In 1944 a group of 70 Brazilian artists offered their works to help with the war effort—shipped across the Atlantic, the works were shown at the Royal Academy and the Whitechapel Gallery in London, before touring the UK, with profits made from the sales going to the RAF Benelovent Fund. Now, 24 works that were dispersed and held in public collections around the UK have been reunited for the first time since they were exhibited more than a half a century ago. Among the paintings on show in The Art of Diplomacy: Brazilian Modernism Painted for War (6 April-22 June) are pieces by some of Brazil’s best known Modernist artists, including Roberto Burle Marx, Candido Portinari and Oswald de Andrade, who pioneered the Antropofágico movement along with its greatest proponent—his wife, Tarsila do Amaral.

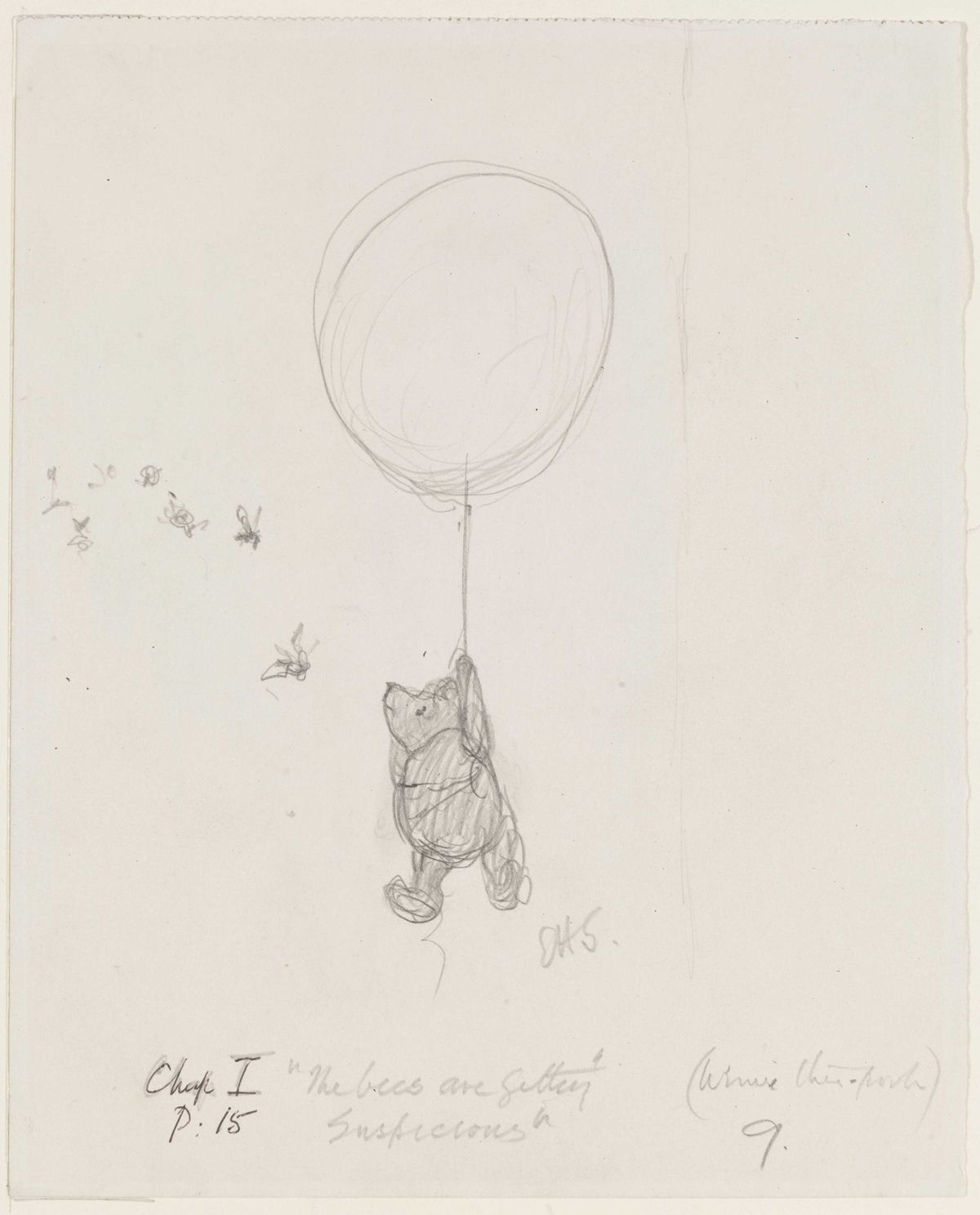

It is the last chance for Pooh fans large and small to see the Victoria and Albert Museum’s Winnie-the-Pooh: Exploring a Classic (until 8 April). The exhibition looks at the real people and inspirations behind the much-loved books written by A.A. Milne and illustrated by E. H. Shepard. The museum is home to the largest collection of Shepard’s Winnie-the-Pooh pencil drawings, and it will be the first time many have gone on show in nearly four decades. There are also a number of immersive sections, recreating some of the best-loved sets from the books, such as Poohsticks Bridge and Eeyore’s house. The museum’s director, Tristram Hunt, said in a statement before the opening, that the museum looked “forward to welcoming another generation into A.A. Milne's magical, intimate, joyous world”.

One of the most celebrated painters of the Spanish Golden Age, Bartolomé Esteban Murillo is now famous for his devotional works and paintings of ragamuffins. This cabinet exhibition at the National Gallery, marking the 400th anniversary of his birth, brings Murillo’s hitherto overlooked work as a portraitist to the fore. Of his 16 securely attributed portraits, six are on display in Murillo: the Self Portraits (until 21 May). The title is slightly misleading as there are only two extant self-portraits; these are the show’s star attractions. Shown together for the first time in centuries are the self-portrait of around 1650-55, the artist as a young man, on loan from the Frick Collection, New York, and that of around 1670, Murillo in his maturity, from the National Gallery’s own collection. Murillo was held in high esteem from his lifetime until the early 20th century when his star waned. Only in recent years has his work, along with other Spanish Old Masters, come back to the fore. This exhibition is a twice-in-a-lifetime chance (it travels to the Frick) to see how the Sevillian master captured the human face.