There was a time, not so long ago, when the word “estate” in an art market context referred to the collection left behind by an august patron of the arts, to be battled for and divvied up across an auction house’s bargaining table. These days, however, an estate battle is more likely to be waged among high-powered dealers for the works left behind when an artist dies.

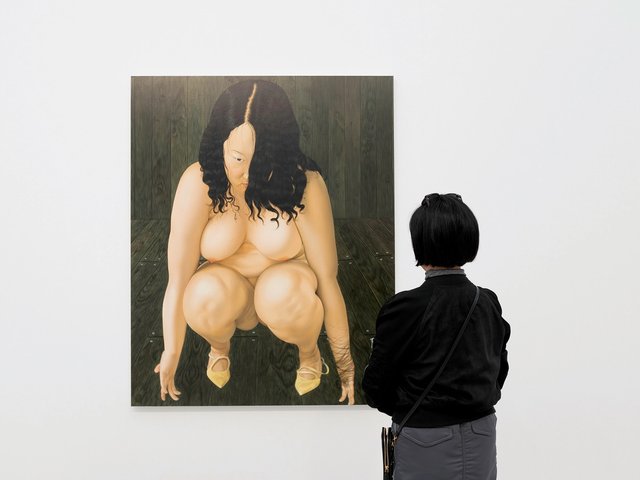

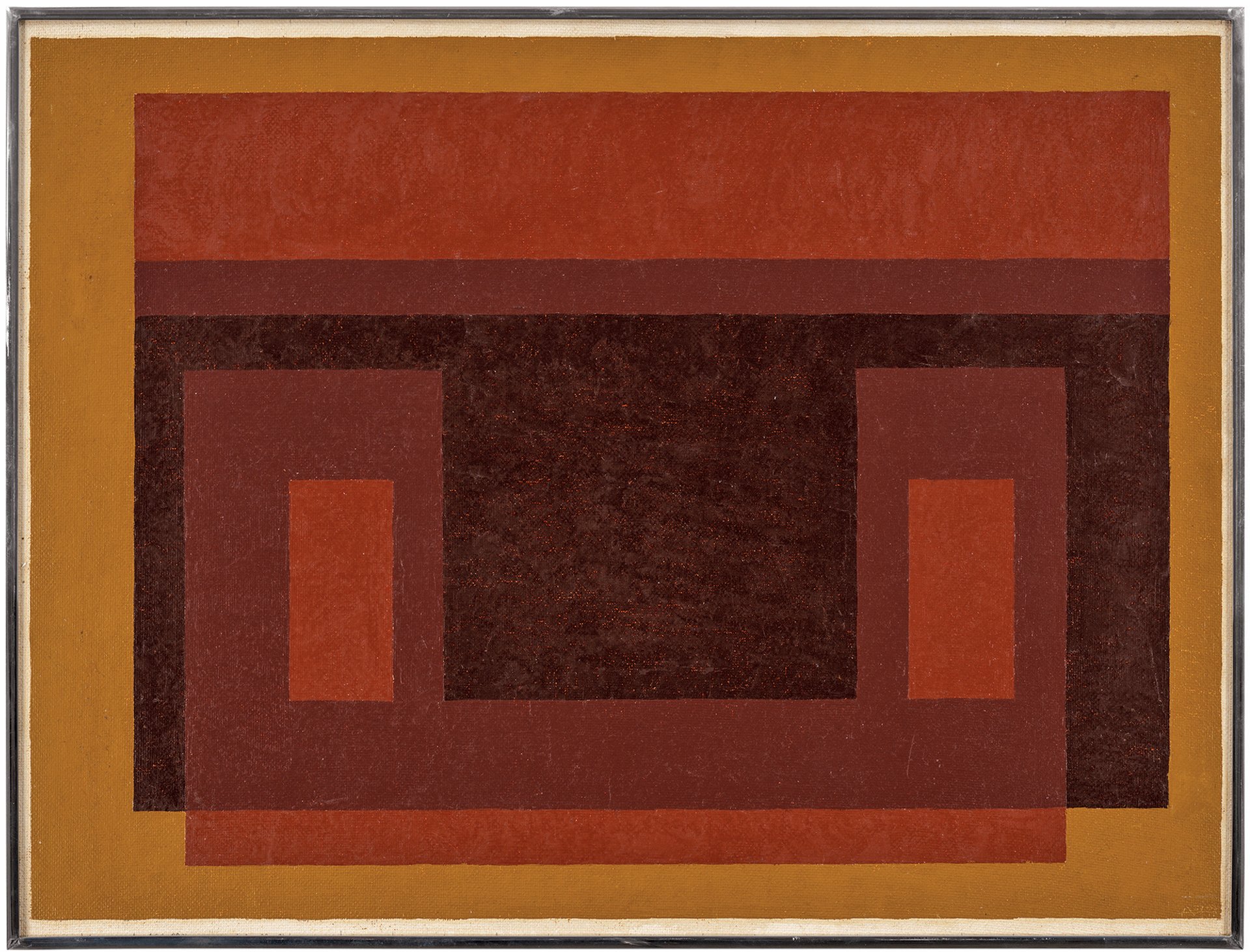

In the past 18 months, galleries have signed dozens of estates, giving them the often-exclusive right to represent the artist’s heirs or foundation in the marketplace: Milton Avery by Victoria Miro; Ruth Asawa, Josef and Anni Albers and Felix Gonzalez-Torres by David Zwirner; Arakawa and Tom Wesselmann by Gagosian; and Lee Krasner by Paul Kasmin. The clamour is not limited to blue-chip names either, with dealers locking in deals to represent less well known names such as Roy Colmer (Lisson Gallery), Carol Rama (Lévy Gorvy), and Lee Mullican (James Cohan). Marc Payot, a partner at Hauser & Wirth, which has recently signed Lygia Pape, Philip Guston, August Sander and Arshile Gorky, says that the ratio of deceased to living artists who have recently joined the gallery is “about one to one”.

Most dealers profess only an interest in bringing the artist’s work to greater renown, but the potential payoff is significant. Artists’ estates are often art rich but cash poor, and may have a strong motivation to sell to defray tax bills or to raise funds to endow a foundation. The works have likely never been on the market; in the best-case scenarios, the artist has hung on to a few prime pieces. For galleries enlisted to handle the sale of estate-held works, the upside can run into the millions of dollars. And the cachet of representing a 20th-century master? Priceless.

Insiders say the contest is stiff. Andrea Danese, chief executive of Athena Art Finance, a boutique lender that provides loans to galleries against their inventory as collateral, has seen an uptick in those seeking to raise lump sums specifically to purchase estates. “Sometimes those transactions are large and they need funding for it. More and more dealers are approaching us around that topic.”

Bidding wars “There’s a real competition among galleries for the top-tier estates,” confirms Loretta Würtenberger, who co-founded the advisory Institute for Artists’ Estates in Berlin last year, spurred by her experiences co-managing the Hans Arp, Sophie Taeuber-Arp and Keith Arnatt estates. “I can definitely say yes, there are bidding wars.” As Payot puts it: “If you have the opportunity to work with a great estate, you need to make up your mind. If you say no, it obviously goes to a competitor.”

“What we’ve got is a perfect storm that I believe has been brewing for some time,” says Adam Sheffer, sales director of Cheim & Read and president of the Art Dealers Association of America. Due to revisionist scholarship around the canon, unaffordable prices for 20th-century titans and an overheated market for emerging talents, Sheffer says, collectors and dealers began looking for works with art historical merit that had not reached their full market potential.

Prior to the boom, he says, estates mostly existed “in a plateaued stage”, where works would be sold off gradually to promote the artist’s legacy in perpetuity. But since estates have been discovered as a new source of material for the primary market, he says, “it went from zero to 60 in no time flat. Things that had been lying fallow for decades all of a sudden had an intense interest around them.”

“I think it’s also something more philosophical,” says Würtenberger. “We do really live in a kind of memory boom. People have an urge to reconnect with their roots. You can see it on a political level, but I think also in reaching out to where we come from culturally, and artists’ estates are custodians of cultural heritage.”

Heirs get wise After the messy execution of major estates such as those of Picasso and Clyfford Still, there is a growing awareness among heirs around the importance of gallery support. “The higher level of professionalism is not just true for galleries, it’s also true for estates and their foundations,” says Payot. “They want partners who support their efforts.” Frank Lord, of the law firm Herrick Feinstein, says: “Artists are becoming much more careful and want to see some kind of order in the way that their estate is handled and ensure that their legacy is carried out.” Further indication of the industry’s focus is the hire by Sotheby’s last autumn of the former Rauschenberg Foundation chief executive Christy MacLear to advise on estate planning for living artists.

A strong estate is in the position to solicit detailed plans and promises from potential dealers. That is just what Nicholas Fox Weber, the executive director of the Josef and Anni Albers Foundation, did when he decided to contract with a gallery, by writing a letter to five dealers under consideration—all copied in with one another—enumerating his desires for the relationship.

Beyond a partner that shared the foundation’s long-term goals and values, Fox Weber “wanted to work with a gallery that understood that it is our commercial arm”, he says. “Success for the Albers was having their work seen and appreciated, and having a larger audience benefit from what they had done. I actually put in the letter, ‘I do not want to have to attend dinner parties and sit next to rich art collectors… If there’s selling to be done, you do it. Don’t expect me to.’” He ultimately chose the David Zwirner gallery.

As usual, the devil is in the detail, and each estate must have a clear idea for what it needs in order to find the best fit. “Representation” can mean very different things, from a non-exclusive consignment relationship with commissions ranging from 20% to 50%, to the gallery buying the estate’s inventory in part or in full, or management of the estate alone or in partnership with other executors. And, as Barbara Lawrence, also of Herrick Feinstein, says: “If you have a taxable estate where the family members are the beneficiaries, as compared to a non-taxable estate where it’s going to a foundation or charity, you have very different goals”.

Harder than it looks A cynical answer to “why estates?” is that by controlling the supply of material, one controls the market—an attractive proposition when primary dealers are feeling pressurised to provide ever more material for fairs. But gallery directors say the reality is not so simple, nor always lucrative.

Like living artists, heirs and executors vary widely in goals and needs. Beyond the grieving process, tax burdens, strong opinions about how to guard a legacy or honour an artist’s wishes, and contentious relations among stakeholders can magnify the usual difficulties. Nicholas Olney, a director at Paul Kasmin Gallery in New York, which represents several estates, including those of Max Ernst, Simon Hantaï, and Robert Motherwell, says: “With an estate, you often have more decision-makers involved. There’s a lot of consensus-building, which can sometimes make things slower.”

There is the matter of how much work remains in the estate—and of what calibre. Jonathan Laib, a director at David Zwirner who was instrumental in bringing in the estate of Ruth Asawa last year, says: “To approach representing an estate with simply monetary gain in mind is a mistake. Nine times out of ten, it’s not going to be a fantastic win.” Marc Payot says: “You have nothing coming out of the studio. The amount of work is defined; that’s it. You need to deal with what there is and not with the potential of what will be.”

Hauser & Wirth had dealt only with living artists until it took on representation of the Eva Hesse estate in 2000. Why? “We saw a possibility to really make a difference there,” says Payot. Hesse was well known in the US for her sculptures, but less so in Europe, and her two-dimensional works had received little attention anywhere. “There was a situation where practically every one of the important sculptures was in an institution. Great paintings and works on paper were still in the estate,” he says. “Now what do you do with that?”

The answer, he found, was to use the less familiar works to encourage curators and writers to think about Hesse in a new way, staging shows both in the gallery and in museums of her mid-1960s works on paper, when she shifted from two to three dimensions. More recently, the gallery showed Philip Guston’s ribald drawings of Richard Nixon, the first time the entire series had been presented in public, on the eve of the US presidential election. “This is a difficult but important body of work,” says art adviser Wendy Cromwell of the Guston show. “In the right context and at the right price, they aren’t perceived as ‘leftovers’.”

Aside from the all-important catalogue raisonné, “commissioning new writers and scholarship is a great way to invigorate the dialogue about the artist’s work and the legacy”, according to Olney. With estates like William Copley’s, which Olney helped reintroduce to the market in 2010, he says: “We dig into archives, rescan material and find great announcement cards, images, notes. We do a lot of pounding the pavement to find all of these things… It’s like gold when you’re trying to put history together and build provenance.” Such publications can also be a bargaining chip when luring an estate.

Beyond financial considerations, estate managers say that the right context is paramount. Philip Rickey, who oversees his father, the US artist George Rickey’s estate, says: “My father would have wanted to be surrounded by artists he felt were his peers.” He chose Marlborough Gallery, which is showing Rickey’s sculptures in London for the first time through 20 May, in part because it represented the artist’s contemporary Kenneth Snelson. When the match is right, it can pay dividends even to the gallery’s younger artists, says Payot: “Doing what we do with estates contextualises the contemporary on the highest possible level.”

Watershed moment Galleries’ investment in estates stands only to grow in the near future. “There is a coming of age of artists over 65, from the Minimalist generation onwards, who are starting to have to answer complicated questions, and a lot of dealers don’t know how to handle it,” says Sheffer. While conflicts of interest must be avoided, “you have to be prepared. These are key issues”.

“We’re in a watershed moment,” agrees Cromwell. “There are so many artists whose markets are strong and who are in the home stretch. I can only imagine how enticing it might become.”