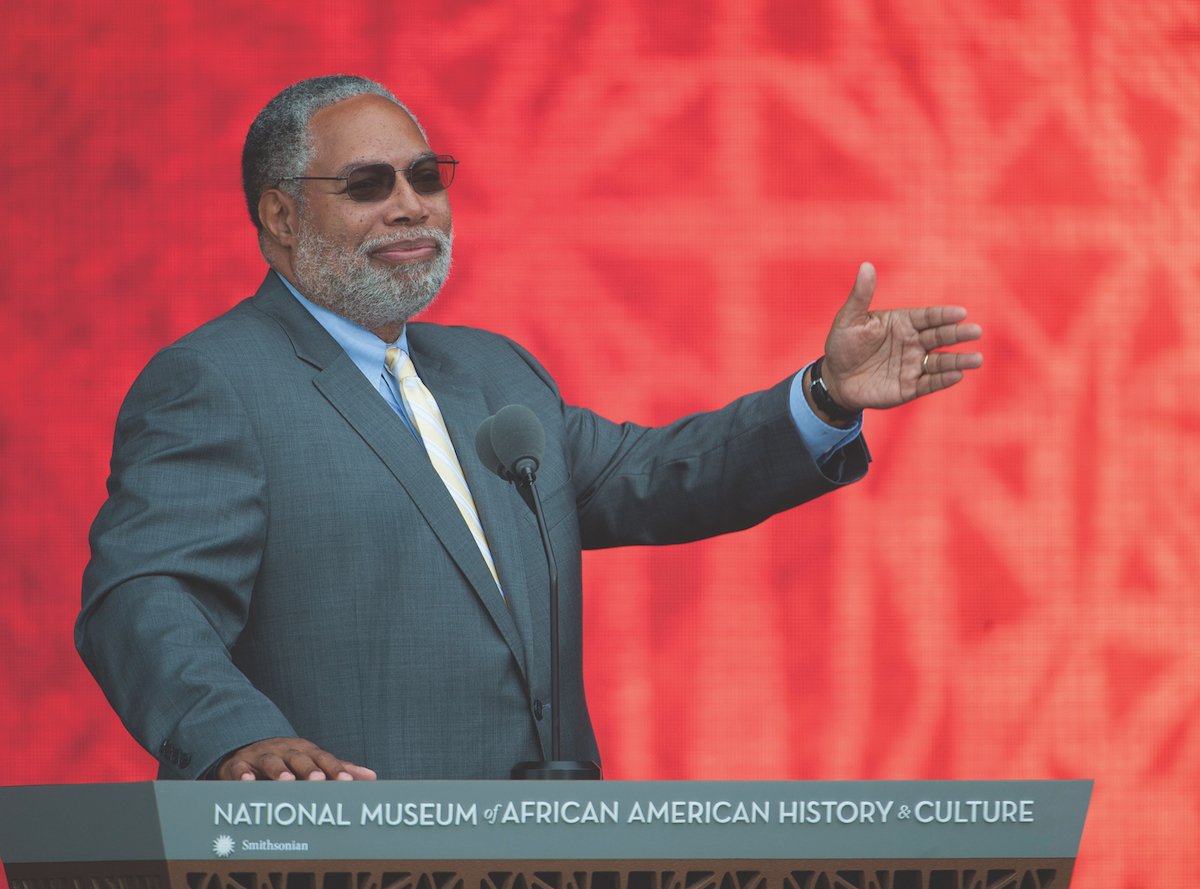

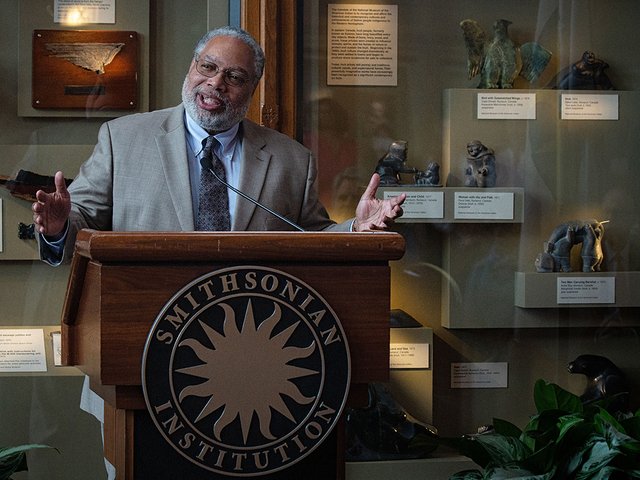

Lonnie G. Bunch III is the new secretary of the Smithsonian Institution, a behemoth with 19 museums, 21 libraries, the National Zoo, multiple research centres and 154 million objects in Washington. The secretary is the boss. A teacher and curator by training, Bunch has had multiple postings at the institution. He was the founding director of the National Museum of African American History and Culture (NMAAHC), building it from scratch over 11 years into one of the Smithsonian’s most visited places. His new book tells the story frankly. A Fool’s Errand: Creating the African American History and Culture Museum in the Age of Bush, Obama, and Trump is a blend of autobiography and institutional history by a leader who knows how to manoeuvre in a large organisation.

The Art Newspaper: What appealed to you about leading the NMAAHC, essentially a start-up?

Lonnie G. Bunch III: When I was offered the job, my board chair at the museum in Chicago [the Chicago Historical Society] said, “Lonnie, what are you crazy? Why do you want to go to a place that has been trying to be built for 100 years? It’s never going to happen.” And then he said, “What you really want to be is the second director, not the first.”

You started with a staff of two and no collection, building, site or money.

Part of it was naïve, but I call it optimism. A good leader has to be an optimist. I knew that only the Smithsonian could pull together the resources and attract the talent to make this work.

Speaking of leadership, I saw a show that you did years ago on US presidents when you were the curator of the National Museum of American History. Which presidents do you most admire?

Franklin Roosevelt, in part because FDR basically said the government’s responsibility is the welfare of its people; Lincoln, because he was a gifted wordsmith; and Martin van Buren, a supreme alliance builder—he reminds us that the best leaders are able to build coalitions and allies.

What are the ingredients of leadership that you brought to the museum and that you bring now to the Smithsonian as secretary?

I think that I’ve always been moved once I discovered that line from Napoleon: that an effective leader defines reality and gives hope.

What are your strategic priorities?

Some of it is finding the tension between tradition and innovation. If 29 million people come to the Smithsonian every year, that means millions more will never get here. And so, thinking about how effectively we reach outside of Washington. And then crafting the virtual Smithsonian [online], which gives people traditional access to our collections and expertise, but also lets them view the Smithsonian through the lens of innovation, race or American identity.

Ultimately my goal is to give America the Smithsonian that it needs and deserves. And that means also being a place that helps people find contemporary understanding and answers to the issues that they’re grappling with in their lives. So if you want to wrestle with the questions of climate change, the Smithsonian can help you think about that. If you want to understand questions of the centrality of race or what the Confederate monuments really mean, the Smithsonian can also help you do that. The Smithsonian is as much about today and tomorrow as it is about yesterday.

The enormously popular National Museum of African American History and Culture Alan Karchmer

What do you think about the state of American history teaching?

I’m always struck by the historical amnesia, that history is this exotic thing about yesterday. If you want to understand our notions of resiliency, optimism or spirituality, you’ve got to look back to history.

Tell me about your experience at the Smithsonian American Art Museum when you were a student at Howard University.

One of the things I love is art and photography, and I think the Smithsonian provided me with an escape in the positive sense. To be able to stroll through it and be made whole again by looking at beautiful art. To be able to see 19th-century images of Frederick Douglass or people that I always wanted to know more about.

Tell me about artists you respond to.

I have been moved by Mark Rothko. I have been taken to places I couldn’t have imagined by artists like Horace Pippin, and [Henry Ossawa] Tanner. I have been moved by looking at the work of Judy Chicago, who introduced me to questions of gender in ways that were really important. I find inspiration when I go into the Freer Gallery of Art and visit the Peacock Room by Whistler.

What are your thoughts on the Hide/Seek show at the National Portrait Gallery in 2010, when then-secretary G. Wayne Clough ordered art by David Wojnarowicz pulled because it offended a congressman? What would you have done?

The key for me is that I don’t ever want to control creativity. If there might be a controversy, I want to know about it ahead of time so I can offer support.

Your master’s thesis was on African American newspapers in the antebellum era. Tell me about your perspective as a partner on the New York Times’s controversial 1619 Project, which puts slavery at the hub of American history and identity.

I am a historian. I think that any time you can illuminate a dark corner, like 1619, that’s part of the job of museums. I was very pleased with it because, in some ways, Americans will never get beyond some of the issues that divide us over race until we understand that history and grapple with questions like slavery. So I might have interpreted something one way versus another way, but I thought what they did could be transformative.