The bluestones of Stonehenge, which form part of the world famous prehistoric monument, were recycled from an even older monument in Wales, according to new research by archaeologists, who have found evidence for a stone circle of identical diameter also aligned on the midsummer solstice at Waun Mawn in the Preseli hills, near where the bluestones were quarried.

Work began on Salisbury Plain—the site of Stonehenge—some 5,000 years ago and the bluestones, later rearranged several times, were the first stone features added to the earliest earth banks and ditches. Some still believe glaciers transported the stones 250km from Pembrokeshire to Wiltshire, but most now accept that stones each weighing up to five tons were moved, probably by water and then dragged over land, by stupendous human effort. The distinctive profile of the monument came from the gigantic sarsen stones added later, which were quarried relatively close by on the Marlborough Downs.

The arc of former standing stones at Waun Mawn during trial excavations in 2017, viewed from the east. Only one of them (third from the camera) is still standing Photograph: A. Stanford

The theory that the bluestones came from an older stone circle in Pembrokeshire follows an excavation led by Professor Mike Parker Pearson, published this month in the journal Antiquity, on the remaining four stones and the empty holes left by stones removed from Waun Mawn. Although dating such sites is notoriously difficult, the team suggests it was built around 3600–3000 cal BC. “This date would place Waun Mawn amongst the earliest stone circles in Britain," the team adds.

Although the dimensions of the two circles match, there would not have been enough stones at Waun Mawn to fill the Stonehenge space, and Parker Pearson suggests that several Welsh monuments may have been dismantled to supply all the stones. Analysis of the cremated remains of early burials at Stonehenge also suggests a Welsh origin for many of the people and even the animals at the site.

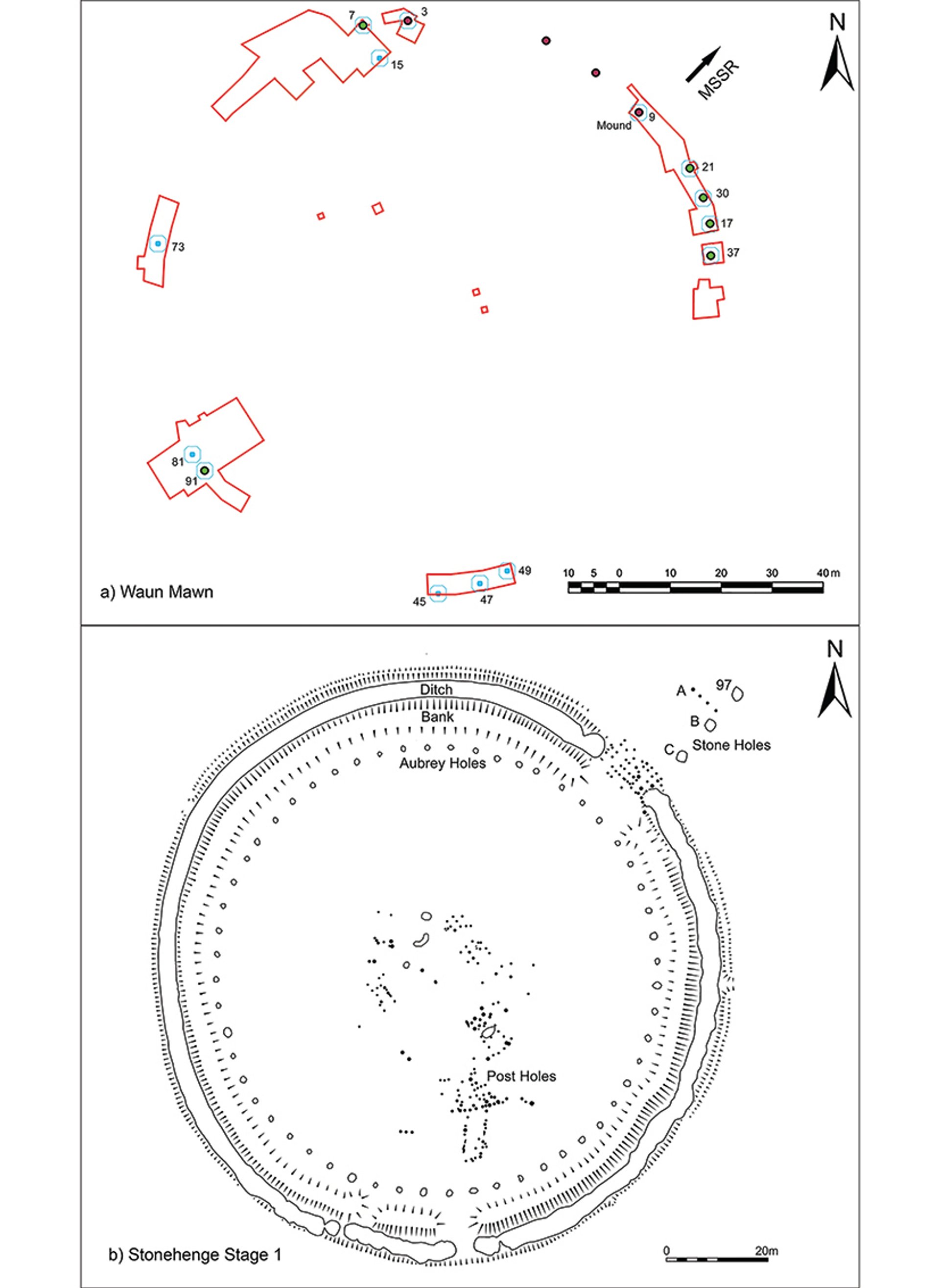

a) Waun Mawn: the excavation trenches (in red) showing the locations of the four remaining standing stones (in red and black), the additional stoneholes (in green and black) and other features (in blue). b) Stonehenge stage one (beginning in 3080–2950 cal BC and ending in 2865–2755 cal BC). © Drawn by K. Welham & I. de Luis

“It seems that Stonehenge stage one was built—partly or wholly—by Neolithic migrants from Wales, who brought their monument or monuments as a physical manifestation of their ancestral identities to be recreated in similar form on Salisbury Plain—a locale already holding a long tradition of ceremonial gathering,” the team writes. “Stonehenge’s first stage may also have served to unite the people of southern Britain. Bluestones were brought to the land of sarsen stones and installed at a sacred axis mundi (world axis or world centre), where the sky and the earth were envisioned in cosmic harmony, and where people of different cultural and regional origins might gather for collective monument-building and feasting."

The authors mischievously suggest that their research bears out “a grain of truth” in one of the earliest Stonehenge legends, the account by the 12th century cleric Geoffrey of Monmouth of how Merlin magically transported a stone circle from Ireland, to mark the grave on Salisbury Plain of Britons slaughtered by Saxon invaders. The stone circle was indeed transported from the west and reused, though the Saxons didn’t arrive until some 3,000 years later.

New theories about the origins of Stonehenge land most years—in 2008 the archaeologists Professors Tim Darvil and the late Geoffrey Wainwright suggested that the spotted dolorite bluestones were believed to have healing powers and so Stonehenge had become the Lourdes of prehistoric Europe—and not everyone will be convinced by this latest theory.

Mike Pitts, who has excavated at Stonehenge and written extensively on its history and archaeology, is sceptical. He said: “That the Waun Mawn circle was the actual source of some of those megaliths is an entertaining idea, but there are too many unknowns. Critically, the dating of the circle is not straightforward, as the authors of the study recognise. The evidence presented does not allow us to say with any confidence whether Waun Mawn was built before, at the same time as or after the first stone circle at Stonehenge—which itself is not directly dated.”

However he described the work that has gone into the study, “after determined fieldwork that many would have abandoned at an earlier stage”, as a great achievement. “It adds to growing evidence for cultural links between the Preselis and Stonehenge that fills out the geological case for the region being the source of some of the Stonehenge megaliths.”

The report is published in the February edition of Antiquity.

• Find out more about recent research around Stonehenge and the planned road tunnel under the ancient site on this week's episode of The Week in Art podcast.