The British architect David Chipperfield’s plans for an urgently needed renovation of the Nazi-era Haus der Kunst in Munich are provoking heated debate in Germany. How much of this Neo-Classical building, conceived by Adolf Hitler as a temple to “pure” German art, should be left untouched and visible?

In 2013, Chipperfield was hired to submit plans for refurbishing the building, which now houses a contemporary art gallery. He proposed rebuilding broad steps leading up to the façade, in order to connect the museum to the city centre. The original steps were removed to make way for a road tunnel, which opened in 1972. Chipperfield also plans to open up blocked skylights to allow daylight into the building. He has recommended making the little-used west wing available for performances, and adding a café and a restaurant. He has also proposed to remove trees that screen the front and back of the building.

For some, his plans amount to a glorification of Nazi architecture. “What is democratic about removing the green curtain and exposing this monumental Nazi architecture to view?” asks Sepp Dürr, a Green Party lawmaker in the Bavarian regional parliament. The parliament’s approval is needed for the renovation to go ahead. No date has yet been scheduled for a vote on the matter.

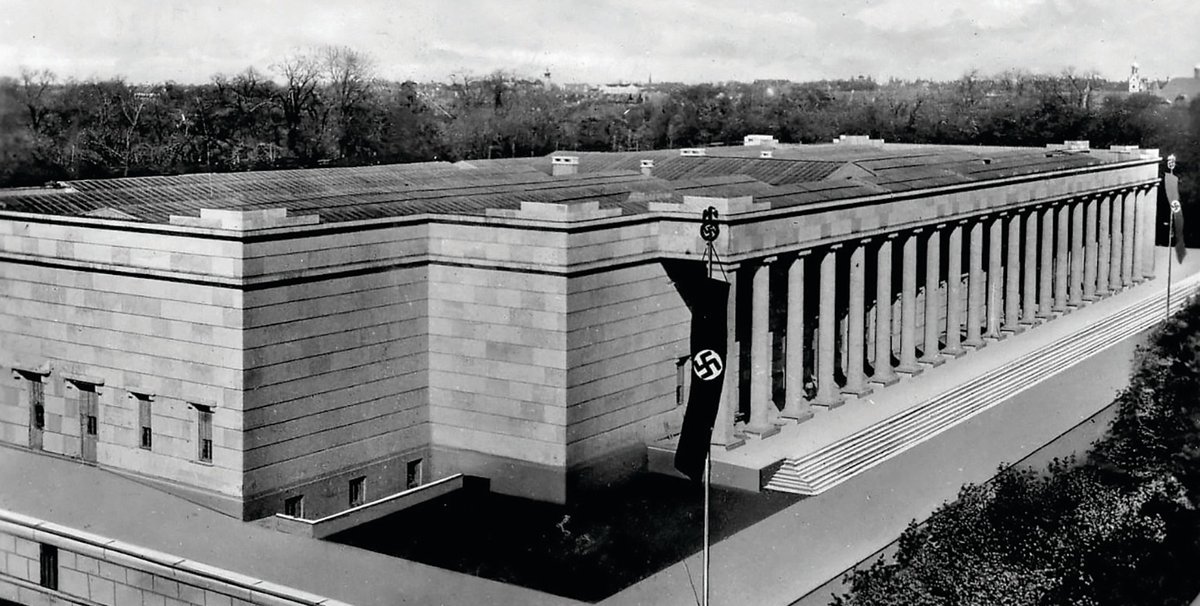

“If you compare Chipperfield’s plans with photos of the Nazi era, you will notice that it looks exactly the same,” the Berlin daily newspaper Tagesspiegel said. “The only thing missing is the gigantic swastika banner on the front.” Winfried Nerdinger, an architectural historian, argues that Chipperfield’s plan to rebuild the steps amounts to “putting the building on a pedestal”.

A “purifying war” Designed by the architect Paul Ludwig Troost, the Haus der Kunst is considered the first monumental public building of the Third Reich. It was opened to great fanfare on 18 July 1937, with celebrations including a historical pageant and a military parade. Hitler used the occasion of his inaugurating speech to vent his spleen at the “degenerate” Modern art that would go on display in the infamous exhibition in the nearby Hofgarten arcades (the show opened the next day), proclaiming “a pitiless, purifying war against the last elements of our cultural decay”.

Built in a natural stone that disguises the then-innovative metal frame construction, the Haus der Kunst is fronted by a row of columns and houses a bomb shelter in the basement. It hosted the Great German Art Exhibition each year from 1937 to 1944. Hitler himself selected exhibits for the show.

Having miraculously escaped the surrounding devastation at the end of the war, the museum became a club for American officers after Germany’s defeat in 1945. Later in the 1940s, it hosted exhibitions of Impressionist and Expressionist art, which were hailed at the time as a “denazification” of the building.

Since then, the Haus der Kunst has become “one of the most stable symbols of cultural integrity”, according to its director since 2011, the Nigerian-born curator Okwui Enwezor. He points to such uncompromising shows as an exhibition of Picasso’s celebrated anti-war painting Guernica in 1955 and Joseph Beuys’s installation The End of the Twentieth Century in 1984. The Jewish artist Mel Bochner recently donated his piece Joys of Yiddish (2012-15) to the museum. Comprising a list of Yiddish words in yellow on black, it traverses the façade of the Haus der Kunst as a reminder of the tragic disappearance of the language from German culture.

Chipperfield argues that, given its more recent history, the building no longer deserves “punishment” for its past. In a letter in the Architects’ Journal, he questioned the need to keep the museum partially screened from view. “We don’t believe that the building can sit any longer in this ambiguous limbo,” he wrote. The Haus der Kunst has moved beyond its origins and “the building that houses this institution must now assume new responsibilities beyond those inherited from its dark legacy, not by hiding its ‘guilt’ but by living with it, overcoming it, subverting it”, he wrote.

No one disputes the fact that the renovation of the Haus der Kunst, estimated to cost around €80m, is necessary. Since its inauguration in 1937, the building has received only patchy repairs. “Water is leaking through the roof,” says a spokeswoman for the museum. Enwezor says the renovation will offer new possibilities for events across artistic disciplines: dance, cinema and contemporary music, as well as visual art.

Chipperfield has experience of buildings that reflect Germany’s past. His reconstruction of the war-ravaged Neues Museum on Berlin’s Museum Island has widely been hailed as a masterpiece. In Berlin, he is also renovating Mies van der Rohe’s Neue Nationalgalerie near Potsdamer Platz.

The Haus der Kunst and the Bavarian state minister responsible for the project, Ludwig Spaenle, support Chipperfield’s plans. For his part, the architect has promised “an open-ended discussion with the stakeholders on the issue of maintaining the trees in the street in front of the main façade”.