A giant worm, a plaster Roman god, a seawall made of soft seating and a giant chalk hairpin have all appeared along the southeast coast of England. The four works of art by Holly Hendry, Pilar Quinteros, Andreas Angelidakis and Mariana Castillo Deball, are part of Waterfronts, a new initiative organised by England’s Creative Coast organisation.

“It’s about engaging people in seeing something that is unexpected, that they might want to look at and find out more about,” the curator of the project, Tamsin Dillon, says. The latest four works join three other outdoor pieces by Michael Rakowitz, Jasleen Kaur and Katrina Palmer, which were unveiled earlier this month.

The seven public commissions, on view until 12 November, are presented with partner art organisations across the southeast, from Metal in Southend-on-Sea to Towner Eastbourne, taking in 870 miles of coastline. Crucially, the works are accessible “at any time of day, so that [the public] don’t have to go into the gallery to see the work,” Dillon says.

Michael Rakowitz's April is the cruellest month. Presented by Turner Contemporary in Margate © Photo: Thierry Bal

However, the curator hopes that the pieces will encourage people who would not ordinarily go to galleries or museums to take that first step. The sculpture of a young soldier by the US artist Michael Rakowitz is “going to be noticed by people who wouldn’t necessarily go to [nearby] Turner Contemporary,” Dillon says. “But the hope is that they will make their way there and go that little bit further.”

“I do think it’s really important to have access to art and culture, as a kind of human right, in one way or another,” Dillon says. “And this project is attempting to make a small contribution in that way.”

Holly Hendry's Invertebrate. Presented by De La Warr Pavilion in Bexhill-on-Sea © Photo: Rob Harris

Holly Hendry’s Invertebrate sculpture playfully points the way into the De La Warr Pavilion in Bexhill-on-Sea, as it literally worms itself around and into the Art Deco building. Inside, the artist’s exhibition Indifferent Deep (until 30 August) appears to have been deposited by the invading creature.

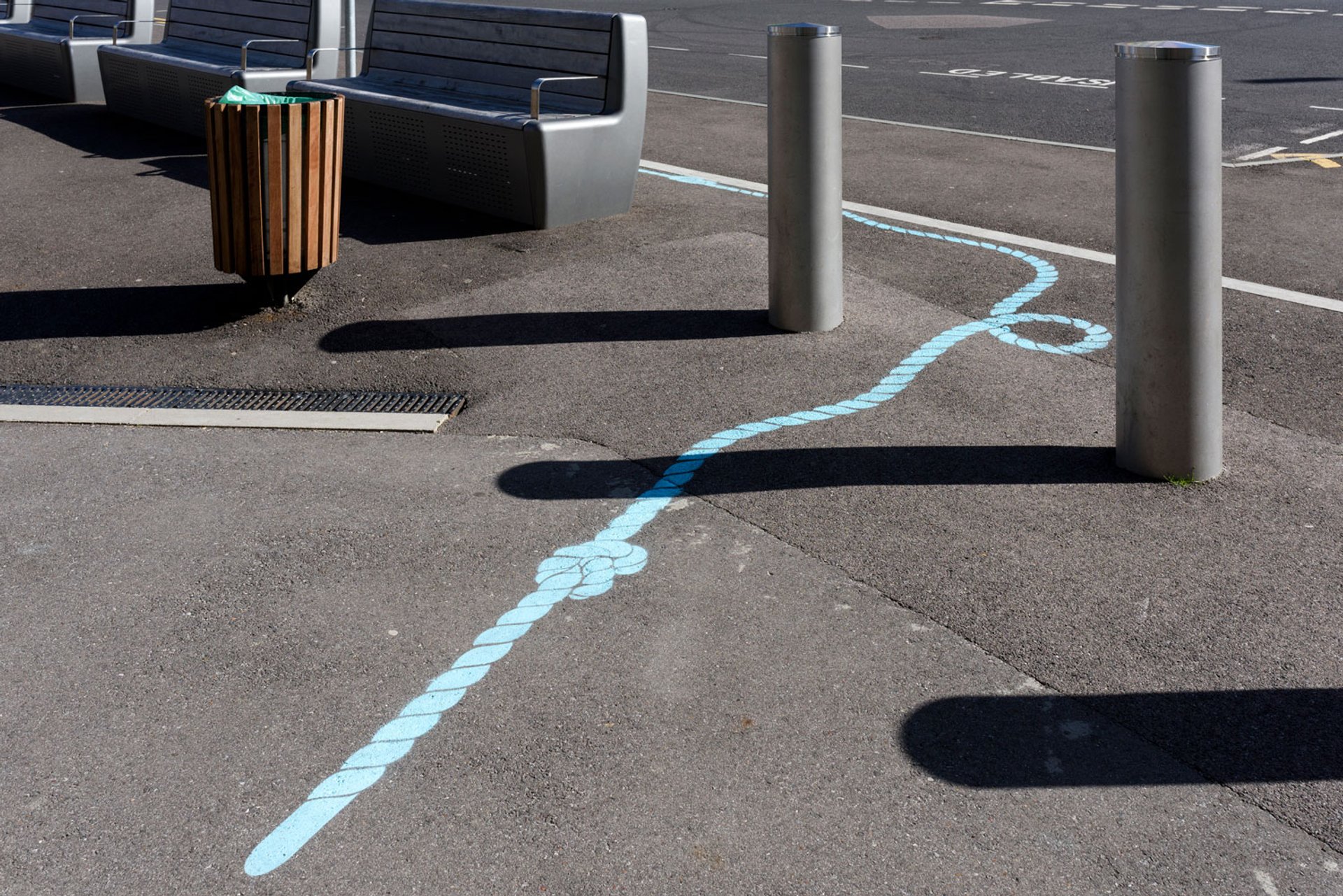

A section of Mariana Castillo Deball's Walking through the town I followed a pattern on the pavement that became the magnified silhouette of a woman’s profile. Presented by Towner Eastbourne © Photo: Thierry Bal

Another work already making waves in Eastbourne is Walking through the town I followed a pattern on the pavement that became the magnified silhouette of a woman’s profile by the Mexican artist Mariana Castillo Deball. Part of the work consists of a rope trail painted onto the town’s streets, leading to small sculptures embedded in the pavement and if seen from above traces the silhouette of a young woman discovered in a local archaeological dig. The piece “has already provoked an incredible response among people there, wondering what they are, wanting to know more and really taking notice of that,” Dillon says.

Mariana Castillo Deball's chalk geoglyph for her work Walking through the town I followed a pattern on the pavement that became the magnified silhouette of a woman’s profile Video still © Modus

Castillo Deball has also created a huge chalk geoglyph drawing of a hairpin, based on one from a nearby archaeological hoard.

Many of the works use the “border between land and sea as their inspiration”, according to the project’s press release. And with the site-specific commissions being installed along the UK’s coastline, Dillon says the ongoing issue of Brexit and climate change were at the forefront of her mind during the commissioning and development stages of the project.

Andreas Angelidakis's Seawall. Presented by Hastings Contemporary © Photo: Thierry Bal

Rising sea levels and the increased use of sea defences are playfully deconstructed by the Greek artist Andreas Angelidakis’s Seawall sculptures, placed outside Hastings Contemporary. On the face of it they appear to be a set of concrete blocks used on shorelines to prevent erosion, but instead are soft sculptures that visitors can play with and recline on.

With regards to her selection of artists, Dillon says that “it was important that they were an international group of people”. And that they had “an interest in different kinds of communities and maybe with a background thinking about diaspora, and how people may or may not have arrived in this country, and crossed that border.”

Janus Fortress: Folkestone by Pilar Quinteros. Presented by Creative Folkestone and a co-commissioned for the Folkestone Triennial © Photo: Thierry Bal

One work that plays with borders is Janus Fortress: Folkestone by the Chilean artist Pilar Quinteros. The giant plaster head of the two-faced Janus, the Roman god of passages or transitions, faces both out to sea and inland. The work, which is made to slowly disintegrate under the elements like the nearby chalk cliffs, is also part of the forthcoming Folkestone Triennial (22 July-2 November). “[T]he specific location of Folkestone makes me think of that region of the country and its history being an important border, as a place of simultaneous entries and exits,” Quinteros says. The artist has called the work “a monument to uncertainty”.

“[Quinteros] wanted it to be placed on the clifftop, with one face looking out at France—whether it is looking wistfully at a place that used to be easier to get to or whether it’s now acting as a guardian of that gateway or border—as its other face is looking into the town,” Dillon says.

Katrina Palmer's Hello. Presented by Metal in Southend-on-sea © Photo: Thierry Bal

Another work that is facing out to sea is the British artist Katrina Palmer’s Hello, based on the concrete sound mirrors built after the First World War to detect incoming airplane attacks. But rather than warning of impending doom, her concrete sculpture greets Europe with a simple “hello”.

Meanwhile, Jasleen Kaur’s sculpture The first thing I did was to kiss the ground in Gravesend was inspired by West Indian immigrants who arrived at the nearby Port of Tilbury, disembarking from the Empire Windrush ship in 1948, while the form of the sculpture is based on Sikh processional floats. The piece, along with Palmer's, is also part of Estuary festival (until 13 June), led by the two art organisations Metal and Cement Fields.

Jasleen Kaur's The first thing I did was to kiss the ground. Presented by Cement Fields in Gravesend © Photo: Thierry Bal

Although the sculptures are visually distinct from each other, Dillon suggests that the link that runs through all the pieces is the artists’ interest in different histories—“how they’re constructed, what they mean and how we put narratives together”.

Another important component of the Waterfronts commissions was the developing of links between the participating art institutions. “For a lot of organisations, particularly in the last couple of years, just keeping things going is hard enough, a project like this can provide a support network for each other,” Dillon says.

As the founder and director of the England’s Creative Coast organisation, Sarah Dance, explains: “At its heart England’s Creative Coast is about connections—connecting people to places, artists with the coast, creative organisations with landscape and with each other, and about connecting visitors to the history of the people and places on the coast.”

Several of the works also have interactive and sound-based elements, activated using QR codes nearby. There are also geocache tours that use GPS locations to tell local histories. For more information on both, see England’s Creative Coast.