The settlement of a legal dispute over Derek Jarman’s paintings has helped clear the way for a major retrospective opening at the Irish Museum of Modern Art (IMMA) in Dublin in November. Including around 80 works, the exhibition is the first to show the full gamut of Jarman’s painting practice.

The case began in 2015, when Keith Collins, Jarman’s long-term companion and the beneficiary of his estate, lodged a civil action against the art dealer Richard Salmon in London’s High Court, requesting the return of all of Jarman’s works of art, which were either in storage or on consignment to various galleries. Collins died suddenly of a brain tumour this summer.

Salmon, who was the sole dealer of Jarman’s paintings and sculptures during his lifetime, says that Jarman stipulated in his will that Salmon should remain in that role “in perpetuity, as he and I had previously agreed”. Jarman died in February 1994.

However, according to Salmon’s lawyer, in early 2015, Collins asked Salmon “to hand over the running of the estate to the Wilkinson Gallery. This Salmon refused to do”. After the dissolution of the Wilkinson Gallery in 2017, Amanda Wilkinson opened her own gallery, taking Jarman’s estate with her.

The legal case was settled in June 2018, shortly before Collins’s death; the terms are confidential. All works have been delivered to Wilkinson, including a group of 30 paintings, which Salmon says are currently subject to an insurance claim.

Wilkinson, who first showed Jarman’s work— an exhibition of his Black Paintings—in 2013, says she cannot comment on the case, except to say that “everything is resolved”, and that she is now able to exhibit and market Jarman’s work. Other paintings are being loaned for the Dublin show by collections in the UK, Ireland and elsewhere.

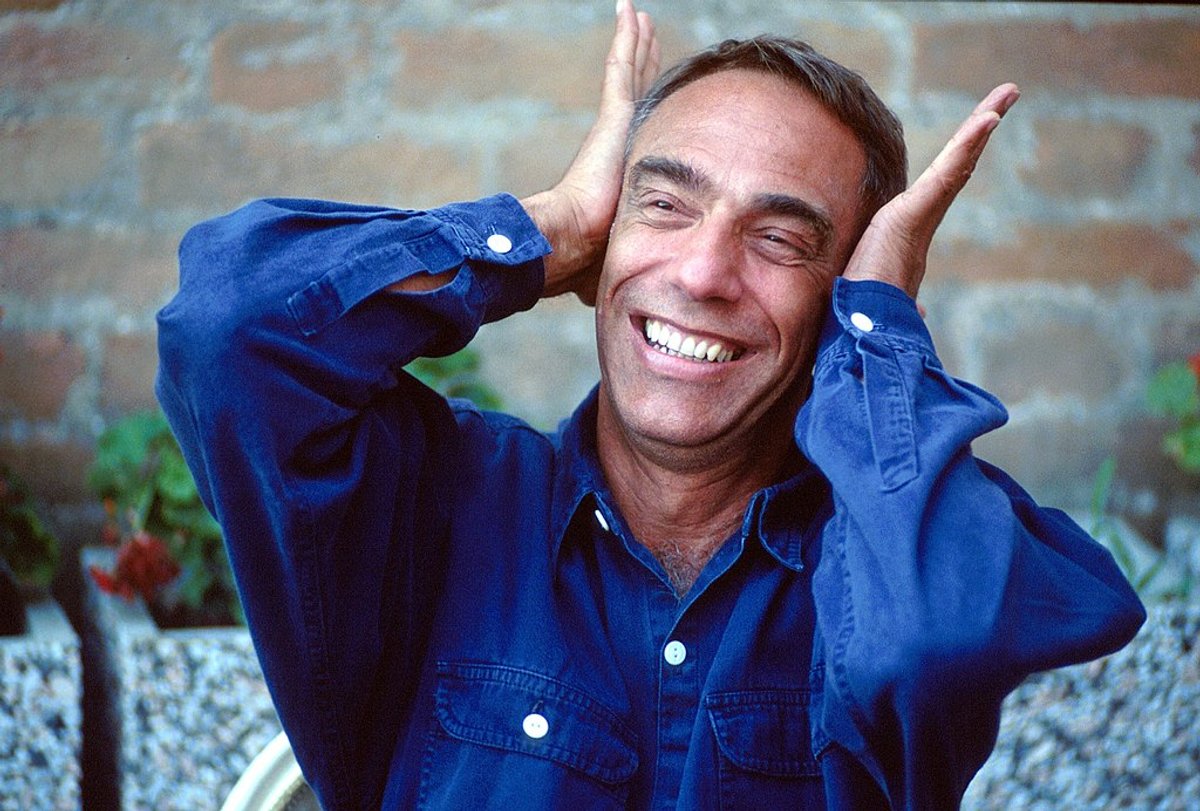

Jarman is best known as an experimental film director and gay-rights activist—and for the garden at his home at Dungeness on the Kent coast, which has been classified as Britain’s only desert. “We don’t know Derek Jarman the painter, but that was his primary practice,” says Sean Kissane, the curator at IMMA. Jarman’s paintings will be shown alongside his Super-8 film experiments; his feature-length films will be screened at the Irish Film Institute.

Jarman is thought to have created around 400 paintings and sketches over the course of his career. “After the self-portraits, he looks to the neo-Romantics, the Two Roberts [artist couple Colquhoun & MacBryde], and produces works that are very inspired by them,” Kissane says. “Then he moves into assemblages that look at people like Jasper Johns, before progressing into more floor-based sculpture.”

From 1990 onwards, Jarman began to incorporate newspapers into his paintings, juxtaposing homophobic stories with headlines such as “Tory peer found with rent boy”. Some of his final large-scale paintings were made in studios owned by Salmon with the help of assistants.

Sourcing works has been like “piecing the jigsaw puzzle together”, Wilkinson says. There are now plans to establish a proper archive incorporating the various aspects of Jarman’s art, working with the producer James Mackay on Jarman’s films and the author Tony Peake on his writings.

The exhibition is timely for a number of reasons, including 2019 marking 25 years since Jarman died of an Aids-related illness. Kissane also points to the current political climate and the effect of Brexit on Britain’s relationship with Ireland.

“We now have a Conservative Party in Westminster that is driving the country off a precipice, and is bringing Ireland with them,” he says. “It’s a very interesting year to reflect on the relationship between Ireland and Britain, and Jarman was one of the real voices to say that there needs to be a push-back against the Conservative government.”