The Grabar Art Conservation Center in Moscow has opened the Ovchinnikov Ikonoteka—a special exhibition space for icons named in honour of the restorer and master copier of icons and frescoes, Adolf Ovchinnikov. The copies on display, made by Ovchinnikov between 1958 and 2016, trace the history of copying in Russia—a practice developed to record religious works threatened by age, neglect and Soviet anti-religious campaigns. The Ikonoteka also holds classes in restoration methods and has programming that encourages contemporary artists to engage with icons.

Ovchinnikov, who still practises his craft at the age of 86, donated 1,700 copies of icons to the Ikonoteka. His approach to restoring these works, which form the basis of Russian cultural and spiritual heritage, is called “copy-reconstruction” and is like a Stanislavsky method of restoration, where the restorer becomes one with the work in order to understand the intentions of its creator. Ovchinnikov feels that restorers, like iconographers, must not take credit for their works. “Iconographers are called upon by society,” says Alexander Gormatyuk, the Ikonoteka’s director who interprets Ovchinnikov’s often complex thoughts. Gormatyuk adds: “The creator of a copy-reconstruction is called upon by the icon.”

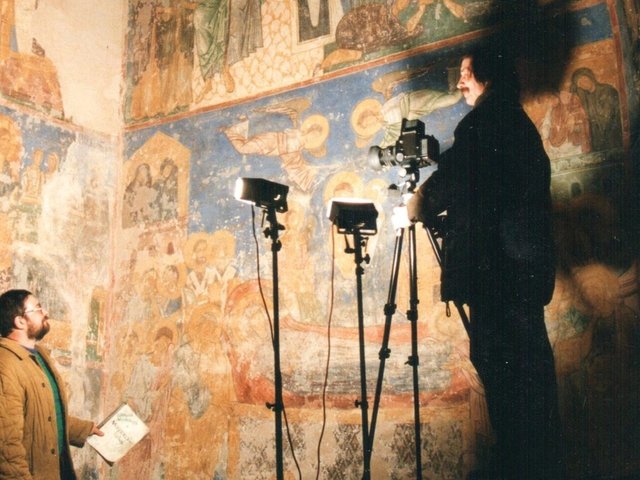

Adolf Ovchinnikov Courtesy of the Grabar Center

Ovchinnikov has said that he has been engaged in a race against time to save these works. “I have copied eight churches in their entirety over my lifetime, and half of these no longer exist,” he told a newspaper in Pskov, a centre of Russian iconography, in 2000. “That’s why we urgently need to create an inventory of copies.”

Ironically, although the Soviet government was behind the destruction of many churches and icons, it was also responsible for funding a coterie of restorers who saved many of these masterpieces. But restorers working in Soviet times were not allowed to refer to them as “icons”, but as “ancient Russian art” so as to strip them of any religious connotation, Ovchinnikov recalls, adding that a KGB officer was stationed at the Grabar to watch over staff.

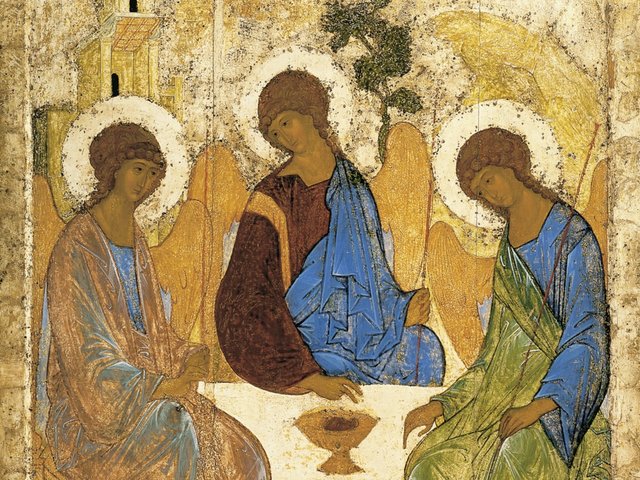

Examples of Ovchinnikov’s work, from the tracings he used to study a work to the final copy-restoration, are displayed at the Ikonoteka, which is located in the former home and studio of the Soviet sculptor Vera Mukhina. They include copy-reconstructions of 12th-century frescoes from the Church of St George in Staraya Ladoga, an ancient fortress in north-western Russia, and seventh- and eighth-century compositions from the David Gareja monastery complex in Georgia. The display also outlines the basics of iconography and visitors are encouraged to look at and touch the raw materials from which the tempera paints used to create icons are created.

Gormatyuk, who is an artist as well as a restorer, is presenting icon restoration in a modern way by commissioning artists to respond to it, such as the artist and designer Andrey Shelyutto who has created an installation out of scaffolding like restorers use as part of their practice. “We are looking for new approaches,” Gormatyuk says. “We want to make this an active place.”