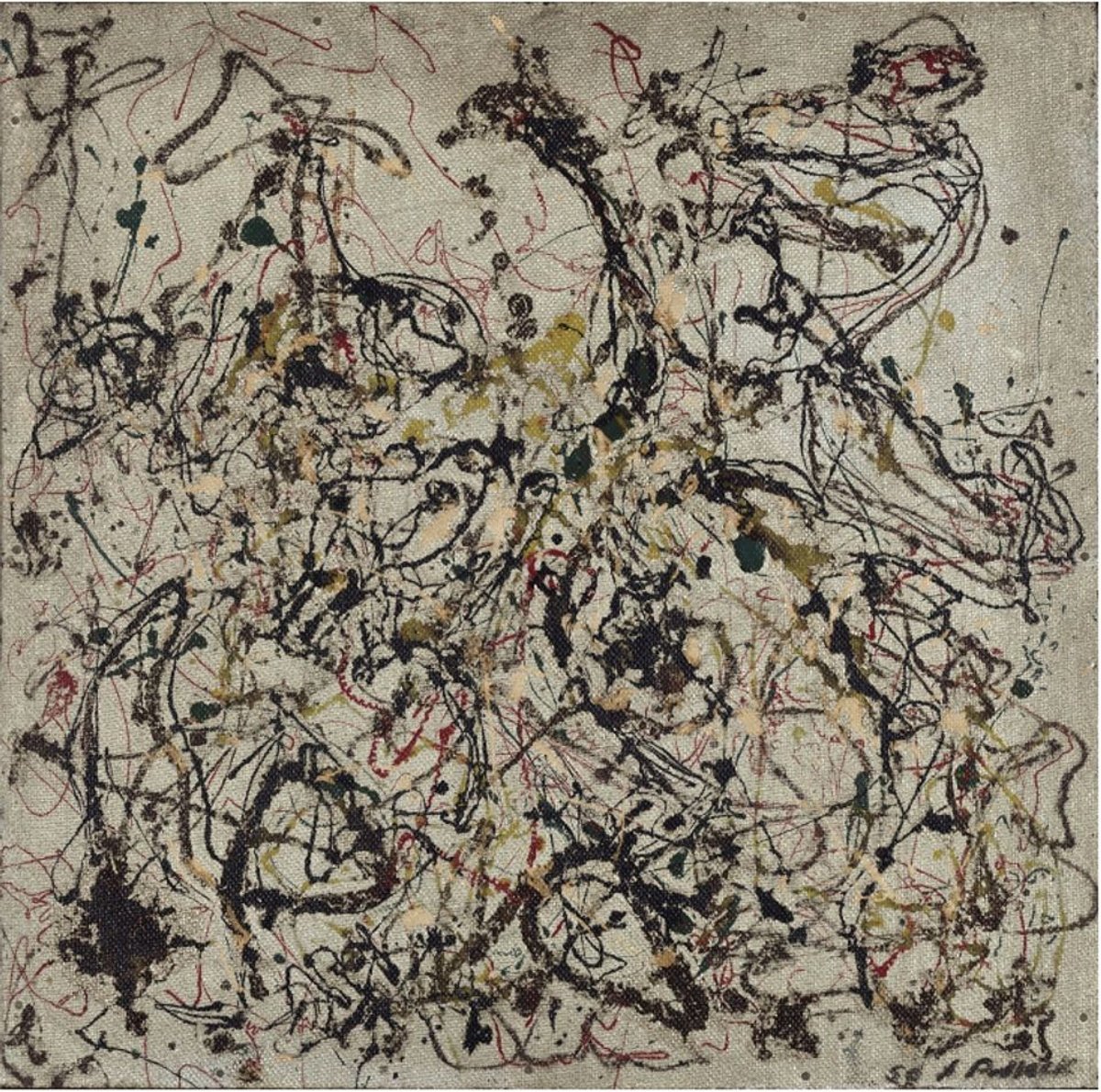

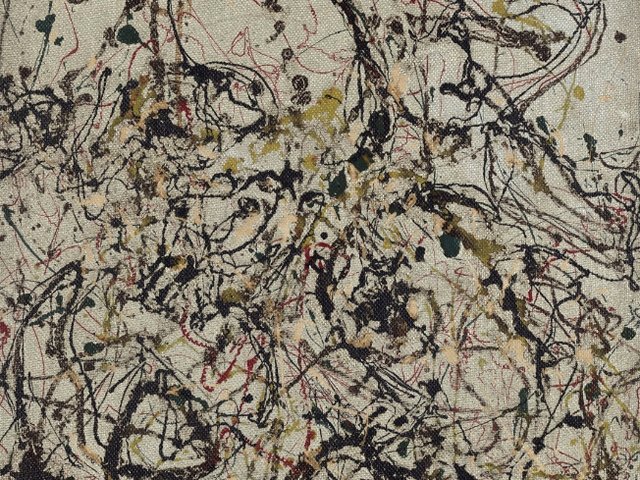

On a heady day back in March 2018, Carlos Alberto Chateaubriand, president of Rio de Janeiro’s Museum of Modern Art (MAM), thought that the institution’s financial problems were solved. He had just received a written proposal from a Brazilian collector offering to buy Jackson Pollock’s 1950 painting No. 16 for $25m. Enhancing the offer, the collector proposed to put it on view for three months every year at the museum as well as keep it in Brazil.

Chateaubriand did not anticipate that four months later, the museum’s board would still be debating whether it should sell the painting. “No one would wait that long–the collector gave up the offer,” he said in a phone interview.

Last week Phillips sold the painting for a figure "in the range" of $13m in a private transaction. The auction house declined to disclose the buyer or the precise sales total.

The painting was the only Pollock on public view in Brazil and the first work of art to be deaccessioned by the museum, although it has considered selling something to help pay off its debts in the past. In 1978 fire swept through its modern reinforced-concrete structure, burning 90 percent of its paintings and 30 percent of its sculptures. Reopened four years later, the institution languished until it closed again because of a lack of funds. At that point its trustees considered selling a Brancusi sculpture to meet the museum's payroll but dropped the plan after a group of patrons stepped in with an ambitious $6m rescue programme.

If in the early 70s, MAM was the hub of artistic activity, today it competes with several other museums in the city that have opened since then, like the Museum of Art, the Museum of Tomorrow, Banco do Brasil’s Cultural Center and the Post Office Cultural Center.

The recent economic crisis in Rio de Janeiro State has slammed the brakes on donations from the museum’s patrons, and MAM receives no money from the federal, state or municipal governments. Nor do Brazilians have the habit of making hefty donations. In March 2018 the museum’s board thus decided to create an endowment through the sale of the Pollock, which was donated by Nelson Rockefeller in 1952.

The museum’s debt is about $3m and its revenue amounts to $1.2m, Chateaubriand says, whereas it needs an average of $2m annually to operate sustainably. The institution says that its electricity bill alone, which covers 24-hour camera monitoring and temperature controls for its 16,000 works, comes to $480,000 a year. The museum must also tend to a film repository that is one of Latin America’s largest.

The Pollock was chosen for sale with the rationale that the artist is not Brazilian and that the museum’s holdings of paintings by foreign artists are not as relevant as its foreign sculpture collection, which includes works by Alberto Giacometti, Barry Flanagan, Henry Moore and Max Bill. Another reason is the painting's value. “Only one work allows us to create an endowment capable of meeting the museum’s needs for a long time, “ the museum said in a statement issued early last year.

But the decision immediately caused turmoil in the local art world. A manifesto signed by more than 170 gallerists, curators, photographers and artists including Waltercio Caldas, Luiz Zerbini, Adriana Varejão, Claudio Edinger and Marcia Fortes, argued that another solution must exist for addressing the museum’s economic problems.

“Selling a Pollock to solve the museum’s economic issues is a very simplistic solution,” said Zerbini. The manifesto cites the case of the São Paulo Museum of Art, which two years ago had a debt 10 times larger than MAM’s and forged an administrative and governance plan that enabled it to recover its financial health.

The museum declined to comment on the manifesto, and Phillips put No. 16 on the block on 15 November. Bidding did not reach the minimum price of $18m, although the painting was on the cover of the catalogue dedicated to the 20th-century and contemporary art evening sale. Then last week Phillips announced its sale in a private transaction. While a spokesman declined to disclose details of the transaction, he said that it was sold “for a price comparable to other Pollock works in the series". Asked if that meant it was in the range of $13m, he replied that it was, which Chateaubriand confirmed.

Chateaubriand emphasises the importance of the money, saying that a shortage of funds for security, temperature controls and the power bill could jeopardise the entire collection. “Imagine the electricity company cuts off the lights for lack of payment,” he said. “It’s better to sell one work than lose 16,000 works.”