The 200-hectare Chateau La Coste estate and vineyard in the Luberon, southern France, is an impressive fusion of art, architecture and viniculture, where visitors are greeted by a Louise Bourgeois Maman sculpture nearly hovering over a shallow pool of water, designed by the Japanese architect Tadao Ando. The latest addition, completed this month, is a new Drawing Gallery by the architect Richard Rogers, which joins buildings by Renzo Piano, Jean-Michel Wilmotte, Frank Gehry and Oscar Niemeyer. And since Rogers retired from architecture last year, this may well be his last work.

The 27-metre rectangular tube that cantilevers out from a hillside between tall pines is a highly functional building, as well as an unexpected intervention in the woodland. The component parts of its structural steel skeleton were all made off-site, at a steel specialist in Braga, Portugal, then packed into two 12-meter-long trucks and driven the 1,500km to their French destination. “It came as a kit of parts, and was built really fast,” says Deyan Sudjic, the former director of London’s Design Museum, who has written a book on the project. “It basically all happened in this pandemic year.”

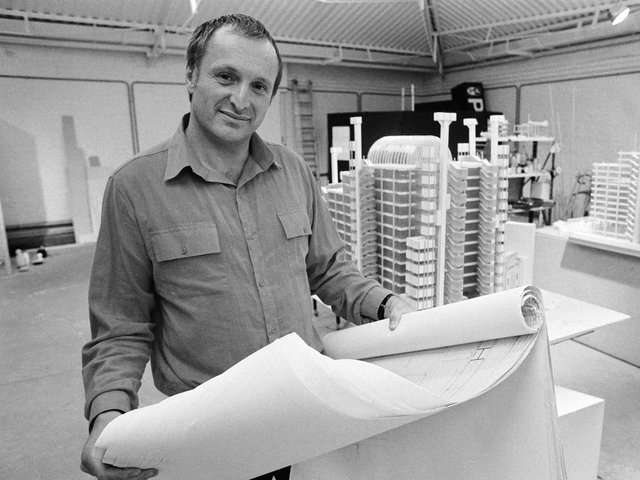

As Sudjic points out, the project rounds off a career that began 60 years ago, when Rogers and another young architecture student, Norman Foster, took a tour of every Frank Lloyd Wright building in the US, after finishing their graduate studies at Yale. “Fallingwater had a big impact on both,” says Sudjic, of the house designed by Lloyd Wright in 1936 that is held up as an ultimate example of how to synthesise architecture and nature.

The Frank Lloyd Wright-designed house Fallingwater had a big impact on Rogers, as an ultimate example of how to synthesise architecture and nature. © Stéphane Abourdaram | WE ARE CONTENT(S)

The Irish property investor Patrick (known as Paddy) McKillen met Rogers in 2001, just after McKillen acquired Chateau La Coste. The two first worked together in 2004, when Rogers Stirk Harbour + Partners (RSHP) consulted on the remodelling of the Berkeley, one of a number of hotels McKillen owns, along with Claridges and the Connaught.

In 2011, McKillen asked Rogers personally to design a gallery dedicated to drawings. The building he came up with ten years later could be a mediation on the medium of paper itself: though it partly sits on a concrete table, and its external armature is in brilliant orange-painted steel, the long box that constitutes the gallery itself looks and feels as light and pure as a sheet of vellum. “The singular open plan, the legible construction, the notion of prefabrication, the use of colour are themes that occur throughout his career,” says Rogers’ son Ab, himself a designer. “The simplest things so often require the most thought.” The tubes are connected by chunky pivots that might remind visitors of the giant geberettes that dominate Rogers projects from the Pompidou Centre to Heathrow Terminal 5.

The view from inside Richard Rogers’ Drawing Gallery at Chateau La Coste © James Reeve

There were rumours that the first show in the new gallery might be work by McKillen’s mother, who is an artist. From December 2019 to March 2020, his sister Trina McKillen, had an exhibition which addressed sexual abuse in the Catholic church. Patrick’s other sister Mara runs the estate.

Another project still unfinished at the Chateau is site-specific housing designed by Jean Nouvel for Louise Bourgeois’s three 9-meter-high towers—I do, I undo, I redo—that were shown at the Tate Modern Turbine hall in 2000. A site has been excavated behind a hill, but the engineering is particularly complicated and has been frequently delayed, so it likely will not be completed for another 18 months.