In two cases testing copyright law in social media, the artist Richard Prince is asking a federal court in Manhattan to rule that two of his Instagram-based works constitute fair use of photographs taken by others.

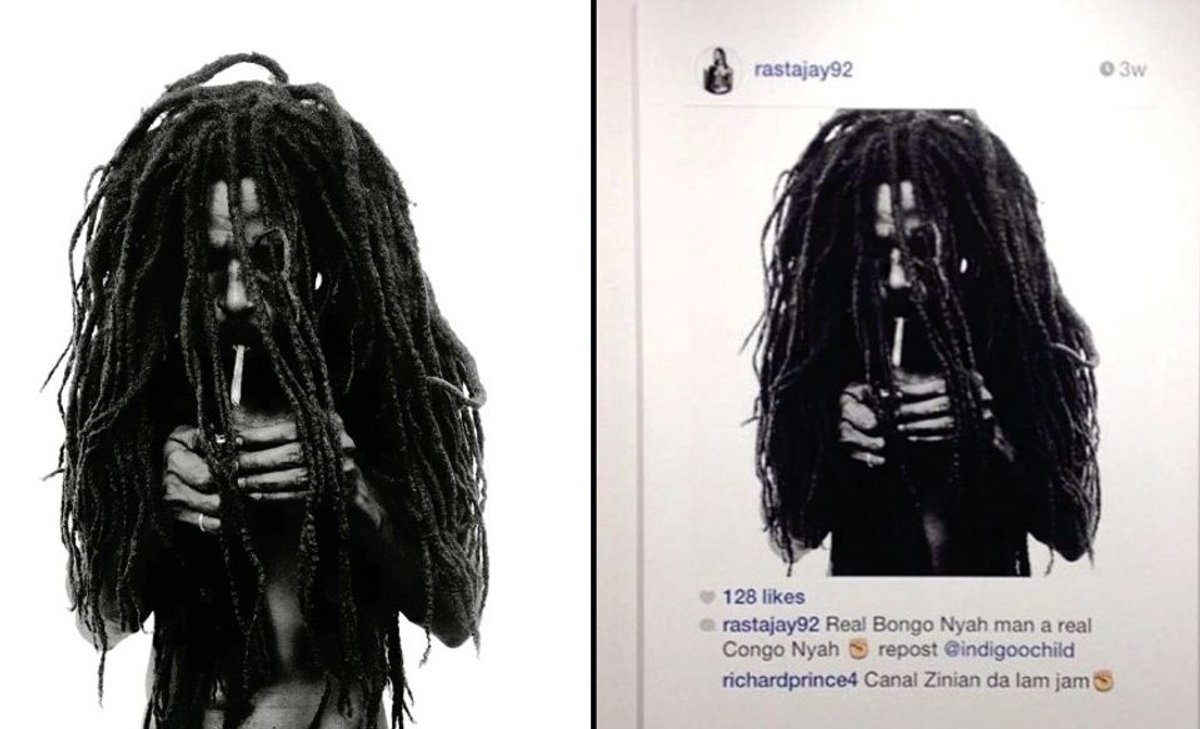

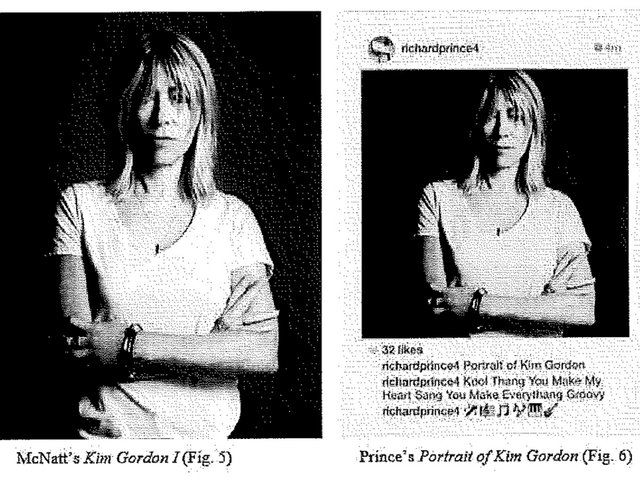

Both are from Prince’s 2014 New Portraits series, in which he enlarged and printed Instagram posts with such images. One uses a Donald Graham photograph, Rastafarian Smoking a Joint, and the other Eric McNatt’s photograph of the musician and artist Kim Gordon. Before enlarging the posts, Prince deleted some comments and added one of his own but left the photographs largely unaltered. Graham and McNatt sued, alleging copyright infringement.

Last year a US District Court judge rejected Prince’s motion to dismiss Graham’s case. To constitute fair use, the judge said, the “reasonable observer” must conclude that Prince imbued Graham’s photograph with new meaning, expression or purpose. Because Prince used essentially the entirety of Graham’s photograph without “substantial aesthetic alterations”, he said, the artist needed “substantial evidentiary support” to prove that his work was transformative.

This time around, in summary judgment motions filed on 5 and 9 October, Prince argues that he had to use as much of the photograph as appeared in the Instagram post to accomplish his purpose. In a 15-page statement calling his iPhone a paintbrush, Prince explains that he wanted “to reimagine traditional portraiture and bring to a canvas and art gallery a physical representation of the virtual world of social media”. Had he altered the photographs, he says, that intent would go unseen.

To establish what a reasonable observer would see, Prince has enlisted art world luminaries. For example, the director of the New Museum, Lisa Phillips, says in court documents, “An image need not be altered to be transformed into a new work of art”, noting Prince’s long practice of appropriation. Whereas the photographs convey meaning about individuals, says Brian Wallis, curator of the Walther Collection in New York and former deputy director of the International Center of Photography, Prince’s works “refer to the way these portraits are already transformed by Instagram as a medium of communication”. And the dealer Daniel Wolf says the meaning in Prince’s works “is not in the photograph; the meaning is in the Instagram”.

The court will also consider how Prince’s works affect the photographs’ market and value. Prince argues the effect will not be negative because he and the photographers appeal to different buyers. Larry Gagosian, who bought the Graham-based work and exhibited it in his gallery, says he would neither show nor buy a Graham photograph. (Gagosian and the gallery, also defendants, have also moved for summary judgment, as has Blum & Poe, which showed the McNatt-based Prince work.) In fact, Prince argues, the photographers benefited from his appropriation. They are now better known, and the price of Graham’s photograph has increased, he says.

The photographers’ court submissions are not due until 9 November, but their experts (whose testimony Prince wants excluded) preview the plaintiffs’ arguments in reports submitted as part of Prince’s motion papers. Nate Harrison, chairman of the media arts department at Tufts University’s School of the Museum of Fine Arts, says that because millions of people recontextualize imagery every day through Internet memes, a reasonable observer would not derive “some intellectual transformation” from Prince’s works. If the Instagram interface with comments and emojis creates new expression, copyright protection for any work posted to social media “would be significantly compromised”, according to June Besek, executive director of the Kernochan Center for Law, Media and the Arts at Columbia Law School.

Amy Whitaker, meanwhile, an assistant professor of visual arts administration at New York University, says, “While I admire the imaginativeness required to wrest [transformative] meaning from five words and one emoji”, that interpretation “rests solely” on the “brand of the artist”.