More than 150,000 people tuned in to watch Sotheby's three-hour cross-category Rembrandt to Richter sale last night, a statistic that probably says more about the state of pandemic social lives than the auction itself.

For those 30 clients who could attend in person at the New Bond Street saleroom, socially distanced auctions looked preferable to the usual school assembly ranks of seats—a few white clothed tables with champagne and canapes as bidding sustenance.

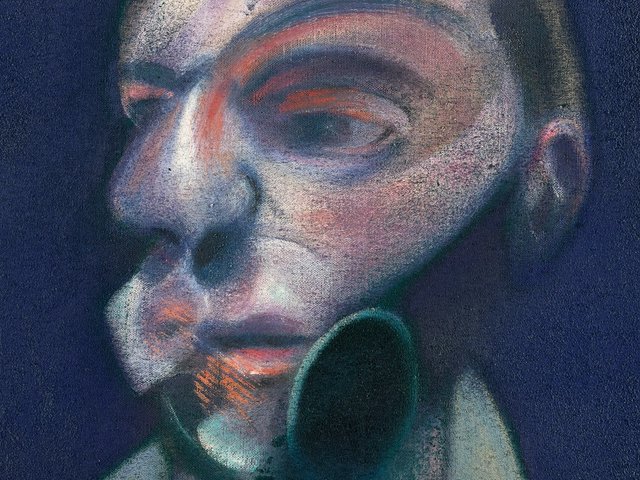

This live-streamed sale was an anomaly—without cancellations forced by the coronavirus pandemic, never normally would there be a major evening sale in traditionally sleepy late-July. But it totalled £128.1m (£149.7m with fees) against a pre-sale estimate of £108.2m-£155.5m, with 62 (95%) of the 65 lots offered sold. Some vendors were evidently a little jittery, as six works were withdrawn just prior to the sale, notably including Francis Bacon’s Study for Portrait of John Edwards (1989, est. £12m-£18m) and Frans Hals’s Portrait of a man (around 1660, est £2m-£3m).

Eleven works were covered by guarantees (all but one of them backed by third parties) including the sale’s top lot, Joan Miró’s vivid blue Peinture (Femme au chapeau rouge) (1927), one of the artist’s dream paintings which had once belonged to Alexander Calder and sold here for £20.6m (£22.3m with fees, est £20m-£30m). The Miró was one of two works consigned by the billionaire investor Ronald Perelman, alongside Henri Matisse’s Danseuse dans un intérieur, carrelage vert et noir (1942), which did not reach its £8m to £12m estimate and sold to the guarantor for £5.5m (£6.4m with fees).

Paolo Uccello's Battle on the banks of a river © Sotheby's

Rarely does a sale skip from a Stanley Spencer view of a cottage garden to a Banksy to a Turner landscape in three lots, nor does a painting by Amoako Boafo, the hot Ghanian artist of the moment, often appear side-by-side with an 18th-century Bellotto. While such an eclectic approach is arguably more interesting than the traditional, narrower departmental offering, the fact remains that auction houses cannot fill evening auctions with one category alone in the coronavirus age—hence the pick-and-mix hybrid. Perhaps it will be a pandemic that finally erases the ever-fainter lines between auction house departments.

Although the mixed hang of Old Masters and contemporary divided some opinions, at Sotheby’s post-sale conference there was much internal congratulating about the extent of “cross-departmental bidding”. There was also some cross departmental rivalry—while Sotheby’s European head of contemporary art Alex Branczik’s highlight was Gerhard Richter’s cloud series painting Wolken (Fenster) (1970), sold for a low estimate £9m (£10.4m with fees), Alex Fletcher, the senior director and head of the Old Masters department in London, was “very relieved to say the Rembrandt made £14.5m and pipped you on this occasion”.

The Rembrandt self-portrait he refers to was the diminutive Self-portrait, half-length, wearing a ruff and a black hat (1632), estimated at £12m-£16m. This was one of the last three Rembrandt self-portraits still in private hands, so although it was compromised by its not-brilliant condition, if you want to buy a Rembrandt, beggars cannot be choosers. The little painting was done by the 26-year-old artist when wooing his future wife, Saskia van Uylenburgh, perhaps to send to her in Leeuwaerden as a memento of her handsome suitor. Following creepingly slow bidding, it sold in New York for £12.6m (£14.5m with fees), setting a new record for a self-portrait by the artist, which previously stood at £6.9m.

Rembrandt's Self-portrait, half-length, wearing a ruff and a black hat (1632) © Sotheby's

More exciting to watch, however, was the bidding war for Battle on the banks of a river (around 1468), the only work by the Italian Renaissance artist Paolo Uccello to appear at auction in living memory. Good Uccello works are like hen’s teeth and this one, estimated at £600,000-£800,000, sold for a big new record at £2m (£2.4m with fees) to the chairman of Sotheby's Europe Helena Newman’s phone bidder, underbid by a contemporary art collector on Fletcher’s phone. The previous record for a Uccello was just £157,250, set at Sotheby’s London in 2008.

The Uccello had a dark past—in 1942, its owner Friedrich Gutmann, an art collector from a Jewish banking family, was forced to sell the painting to Hitler’s art dealer, Julius Böhler. Gutmann was later murdered at Theresienstadt concentration camp and his wife, Louise, gassed at Auschwitz. The vendors at Sotheby’s, an Italian family, recently learned about its past and decided to sell the painting at auction as part of a settlement agreement with the Gutmanns’ heirs.

The Uccello was one of three restituted works in the sale, alongside Bernardo Bellotto’s Dresden, A View of the Moat of the Zwinger (around 1758)—sold for £4.6m (£5.4m with fees) against a £3m-£4m estimate—and a sottobosco still-life from the 1660s by Abraham Mignon, which had recently been returned to the heirs of the Jewish publisher Ludwig Traube and his widow Gertrud Bühler, who had been forced to sell it when she and her second husband fled Berlin for Brussels.

The contemporary works in the sale were a mixed bag. A triptych of paintings by Banksy, entitled Mediterranean sea view 2017, made the second highest price at auction for the Bristolian artist, who donated the paintings to the auction to raise funds for Basr hospital in Bethlehem. Banksy had made the works—three gaudy seascapes reworked with lifejackets and buoys strewn on the beach—in response to the loss of life caused by the migrant crisis and the trio have hung in the artist’s Walled Off hotel in the Palestinian town of Bethlehem since 2017. Estimated at £800,000-£1.2m, the triptych sold for £1.8m (£2.2m with fees) to Sotheby’s senior director of private sales Isabelle Paagman’s phone bidder.

Eighteen lots came from a family collection of European avant garde art, all of which sold for £47.6m with fees. “It was a testament to taste—an old school collection, the type of which you could put together in the 80s,” says Newman of the collection. Seven of the works, including Fernand Leger’s Nature Morte (1914), sold for £10.5m (£12.2m with fees, est. £8m-£12m), were bought from Galerie Beyeler in the 1980s. Also from this collection was Henry Laurens’s unusual stone relief Le Boxeur (1920), which sold for a record £1.7m (£2.1m with fees), far surpassing a £250,000-£350,000 estimate.

Joan Miró'sPeinture (Femme au chapeau rouge), sold for £22.3m with fees © Sotheby's

Bridget Riley’s Cool Edge (1982) was the only work in the evening sale to be offered from the collection of the embattled British Airways—the other 16 lots will be sold in Sotheby's online auction of Modern & Post War British Art (until 30 July). Cool Edge, estimated at £800,000 to £1.2m, sold for £1.5m (£1.8m with fees), further evidence, Newman says, of a rise in the British artists work in recent years which has been “cemented” by London’s Hayward Gallery’s recent solo show of her work. Another British female artist whose work performed well was Barbara Hepworth—the sculptor’s Orpheus (Maquette I) was pursued by five bidders to sell for £1m (£1.3m with fees) nearly four times its high estimate of £250,000 to £350,000.

“I thought it was a successful sale; Sotheby’s worked hard to get some good works and it proved that freshness to the market and quality are still the main driving factors [for sales],” says Emma Ward, the managing director of the London-based advisory Dickinson, who was one of the few in the New Bond Street saleroom last night and praised Sotheby’s slick set-up (and comfortable seats) for the three and a half hour sale. “The art market seems to be much more resilient than many other markets at the moment, and we’re not really seeing any distress sales as yet,” Ward says, adding that the Hepworth and Laurens were two works that stood out in particular to her before the sale.

A final mention to Simon Stock, who was back on the phone bank again having rejoined Sotheby’s from Gagosian. He returned to the auction house just before the sale as a senior specialist, Europe and Asia, Impressionist and Modern art, charged with building the market for western art in Asia.