One of Poland’s most prominent museums, the European Solidarity Centre in Gdansk, has strongly opposed an attempt by the country’s culture ministry to change its structure. In a resolution passed on 2 February, the museum’s advisory council said recent proposals entailed making part of the institution subject to the ministry, in effect destroying its independence.

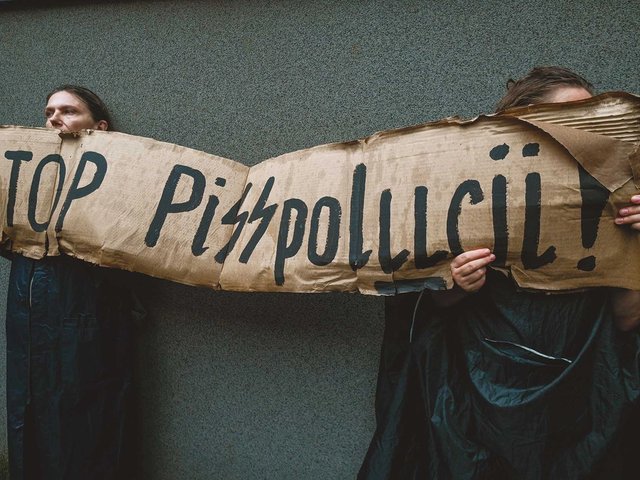

The dispute is taking place amid a fractious cultural climate in Poland, with the governing Law and Justice party (PiS)—of which the Minister of Culture, Piotr Gliński, is a leading member—accused of trying to dictate the way in which the past is discussed.

To date, much of the focus has been on Poland’s Second World War history. A so-called “Death Camp” law, intended to criminalise talk of Polish complicity in the Holocaust, was introduced in early 2018 but later watered down after international condemnation. Meanwhile, Gliński stands accused of manoeuvring his ministry into a position of political control over both the Museum of the Second World War in Poland in Gdansk and the POLIN Museum of the History of Polish Jews in Warsaw. In the case of the European Solidarity Centre in Gdansk (ECS), though, it is Poland’s more recent history that has come under scrutiny.

Remembering the freedom movement

The ECS opened in a specially commissioned building in 2015 to commemorate Solidarity, the anti-communist movement that began in Gdansk’s Lenin Shipyard in 1980 and eventually led, in June 1989, to the first free elections in the former Eastern Bloc. The museum was closely associated with Gdansk’s liberal-leaning mayor, Paweł Adamowicz, who died after being stabbed by a 27-year old man with a history of violent offences at a charity event on 13 January. Adamowicz’s body lay in state at the ECS prior to his funeral, attracting large numbers of mourners. His attacker is not known to have held political affiliations, but many have linked the killing to what they see as an increasingly vitriolic public discourse.

The ECS has gained international plaudits—it was awarded the Council of Europe Museum Prize in 2016—and until recently enjoyed cross-party political support in Poland, with its annual budget co-funded by the Ministry of Culture, the City of Gdansk and the Pomerania Province. However, last October the Ministry of Culture announced it would reduce its funding from just over PLN 7m ($1.8m) in 2018 to PLN 4m ($1m) in 2019. At a meeting in January with the leaders of Gdansk and the Pomerania Province, the Minister of Culture, who is also Poland’s Deputy Prime Minister, proposed a series of changes to the structure of the ECS. These included giving the ministry the right to appoint a deputy director, as well as the creation of a new department named after one of Solidarity’s co-founders, Anna Walentynowicz, who publicly fell-out with the movement’s figurehead, Lech Wałęsa. A critic of Poland’s post-communist political settlement, Walentynowicz was killed in the 2010 plane crash that claimed the lives of many of the country’s leading public figures, including the then president, Lech Kaczynski.

Gliński’s spokeswoman argues that the ECS is currently failing to represent “all the heirs to the Solidarity idea”, by excluding certain individuals from the story it tells. Noting that the City of Gdansk is the “main organiser” of the museum despite providing “a subsidy almost two times lower than the ministry”, she says that the ECS “should not—and cannot—be used instrumentally for day-to-day political and party activities.”

Though the spokeswoman did not refer to them by name, Gdansk is known as a stronghold for the liberal-conservative Civic Platform party which is currently the main opposition party in the national parliament. Adamowicz was a member of this party until turning independent in 2015.

Explaining that the ministry is now “of the opinion that the organisers should have influence on the functioning of this institution according to their financial involvement”, the spokeswoman says the proposals are not intended to interfere with the museum’s current programme, “but only supplement it with elements that we believe to be missing.” The spokesperson added that the ministry’s 2019 contribution to the ECS budget marked a return to a level agreed in 2007 and that any contributions above that figure had been made “voluntarily”. The ministry has indicated that it will increase its funding on the condition that its proposals are accepted.

The museums’s other main funders have sided with ECS in the dispute while the institution’s deputy director for research, Jacek Koltan, rejects the culture ministry's insinuation that the ECS has been operating under political influence. He argues that it is the ministry’s own proposals that contravene the legal requirement for cultural institutions in Poland to remain independent from political control. He says that the museum’s current operational structure, which places full authority in the hands of the director, Basil Kerski, would be severely compromised by the appointment of a deputy responsible to the ministry.

Despite describing the current situation as a “very dark moment”, Koltan says the ECS remains optimistic, not least because a series of crowdfunding initiatives in support of the museum have quickly raised almost PLN 7m, more than compensating for the reduced funding from the ministry. The deputy director suggests there is a possibility more long-term funding could be found from regional sources, removing any future reliance on the ministry, but that the legal implications of this are not yet clear. Koltan also says that the EU, which provided almost half of the PLN 231m (€ 53,3m) required to build the ECS, may have a role to play in resolving the dispute.

According to Jakub Dąbrowski, a professor at the Academy of Fine Arts in Warsaw, the Ministry for Culture’s interest in the ECS fits the wider narrative of a “conservative revolution” currently underway in Poland. Having won an unprecedented majority in the 2015 parliamentary election, Dąbrowski says that PiS interpreted the results “as a people’s (Sovereign’s) will to change the dominant political, economic and social order.” He adds that this previous order was founded on what PiS sees as a “corrupt agreement” made in 1989 between the liberal part of the Solidarity-led opposition and the communist regime. “PiS emphasizes constantly that it carries out the Sovereign’s will [as] expressed in democratic elections,” Dąbrowski adds.