The Piero Manzoni Foundation in Milan has come under fire after it revealed that it destroyed 39 works—mostly paintings, purportedly by the late artist—in December.

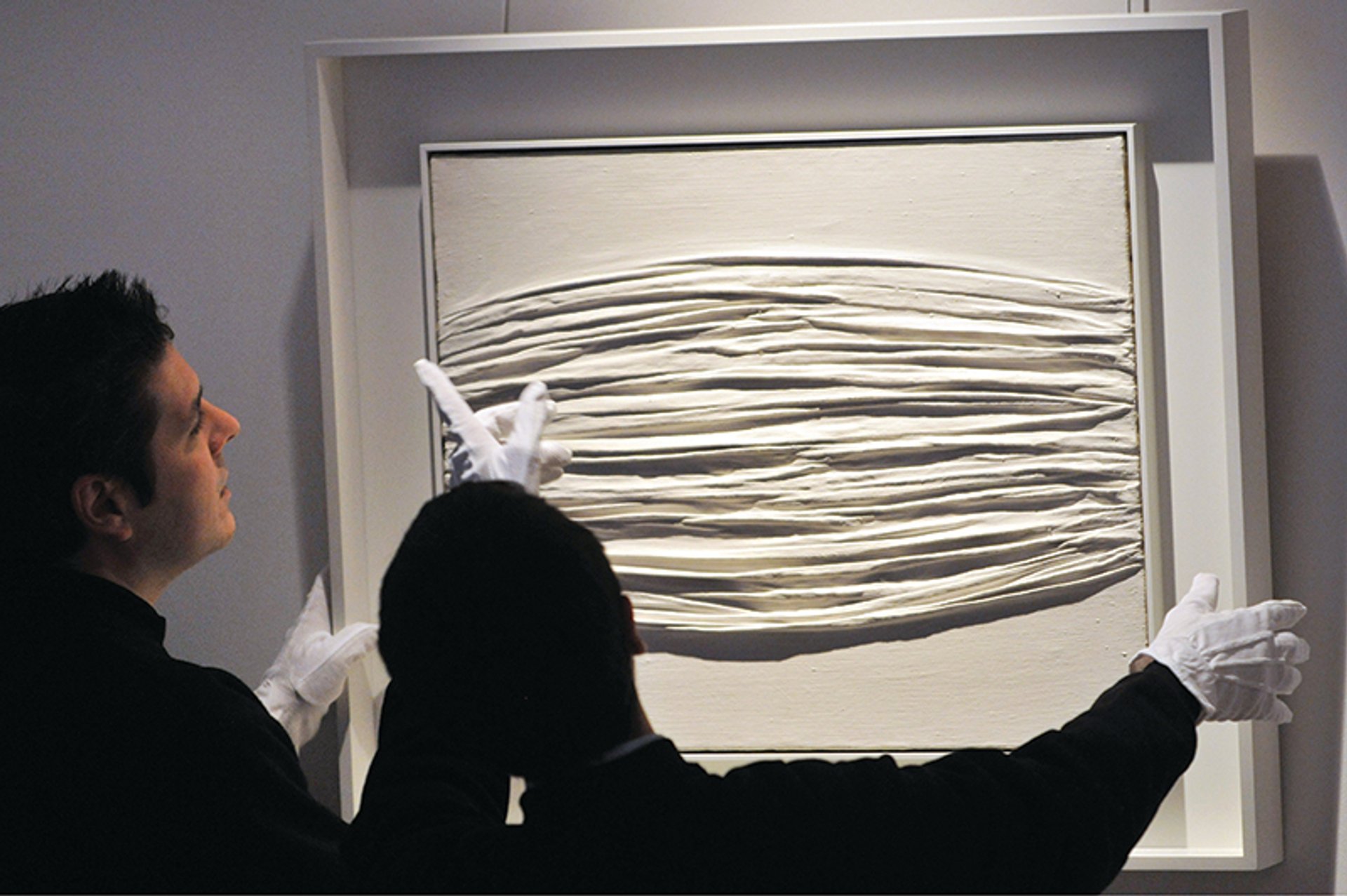

Piero Manzoni, who died at the age of 29 in 1963, is among the most sought-after Italian post-war artists, known for serial monochromes made by dipping canvas in liquid kaolin, a clay used to make porcelain. These works, which he called Achromes, have fetched up to $20m at auction. He is also known for canning and selling his own excrement at the same price, per gram, as gold.

The foundation’s action was the culmination of a long-running dispute with the owner of the works, which resulted in conflicting court orders. Now the organisation is facing accusations, from a lawyer involved in a separate dispute with it, that it “decrees works to be fake at its pleasure, rewriting bits of the artist’s life to suit its purposes”. The lawyer in question, Lionel Ceresi, has suggested in court that the foundation manipulates the authentication process to inflate the value of its own holdings, allegations the foundation strenuously denies.

The cases, among at least 20 that the Manzoni Foundation has fought in court, highlight the powerful role the judiciary plays in matters of authentication in Italy.

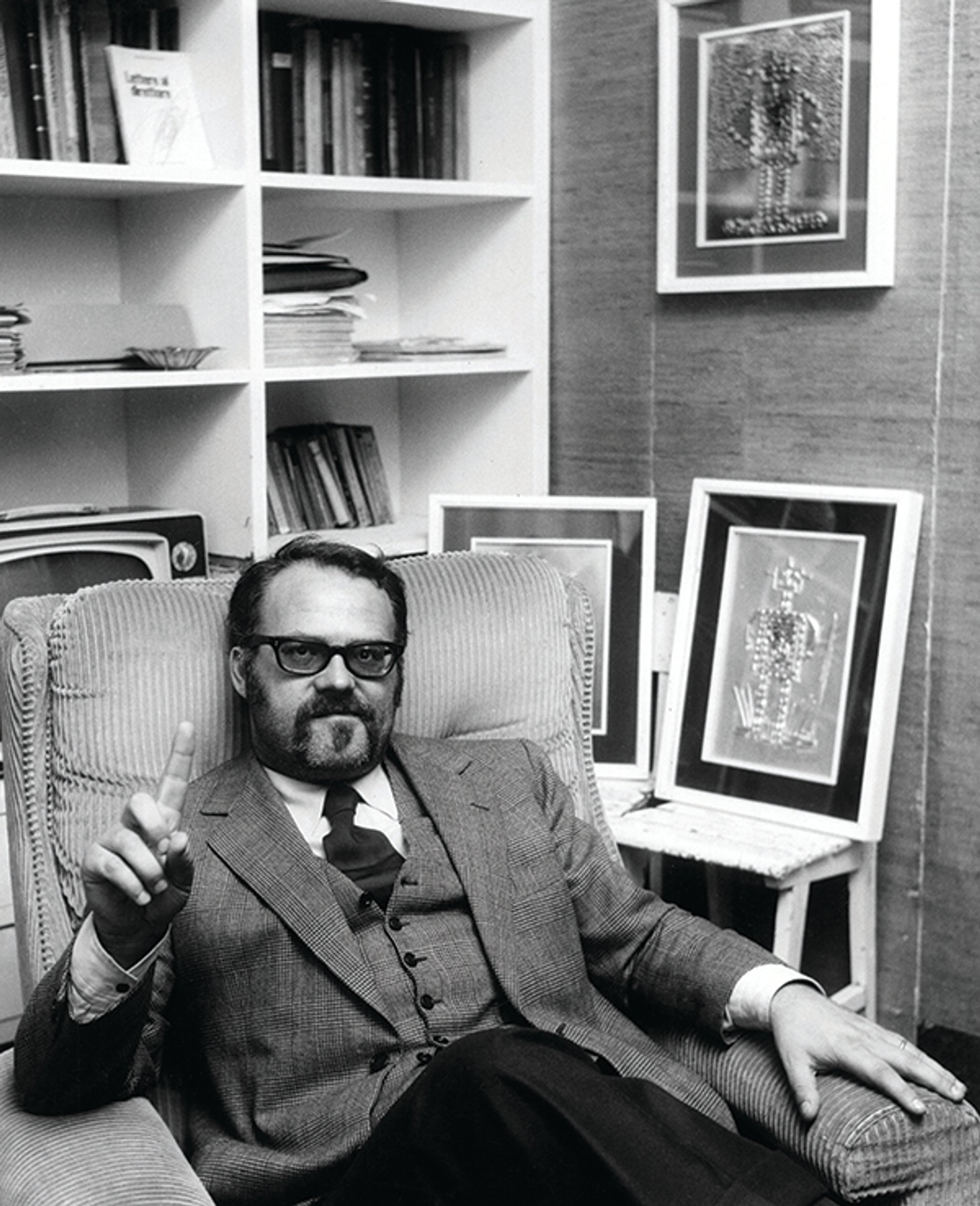

The Italian opera singer Giuseppe Zecchillo Leonida Barezzi/Mondadori Portfolio via Getty Images

Zecchillo dispute

In 1963 the Italian opera singer Giuseppe Zecchillo moved into the space in Milan that Manzoni had used as his final studio. Zecchillo was a collector who described himself as a friend of the late artist. He said he obtained works directly from Manzoni and bought others from friends of the artist and dealers. The foundation disputes that he was close to Manzoni.

Starting in 2000 and up to 2002, Zecchillo presented his collection of Manzoni works, which included many Achromes, to the Piero Manzoni Archive, which became the Piero Manzoni Foundation in 2009.

Zecchillo asked the archive to authenticate his works and include them in the catalogue raisonné that was then being put together by the Italian curator Germano Celant (it was published in 2004). However, 39 of Zecchillo’s pieces were rejected as fakes, and the archive sued the collector, seeking court approval for destruction of the contested works.

In court

The case was considered first by a civil tribunal in Milan, which focused on analysis of the artist’s signature and his name written in block capitals on the back of the disputed canvases. The judge’s ruling, issued in October 2006, noted that the court had relied on graphological analysis because the scientific examination of the paintings’ constituent materials was not “reliable”, as these were easy to obtain and forgers were well versed in the techniques used by the artist. The graphologist believed the writing on Zecchillo’s paintings to be fake; the judge concluded that the paintings were forgeries and ordered their destruction at the end of the civil appeal process.

Meanwhile, in a separate criminal trial, Giuseppe Zecchillo stood accused of hiring forgers to create the disputed works with a view to selling them. A ruling in this case was issued in January 2009. This judge dismissed graphological evidence as “problematic” and “not scientific”. Like the civil judge before her, the criminal judge noted that technical analysis of materials in Manzoni’s paintings was useless in determining the authenticity of his work because it was easy to obtain the same everyday materials as those used by the artist and dating from the same period. She also dismissed the stylistic evaluation of the disputed paintings by art historians, including Celant, because of the “extreme subjectivity” of those assessments.

The judge concluded that there was not enough evidence to determine whether the paintings were real or fake and that there was no proof that Zecchillo had hired forgers to make them. She acquitted the collector on all charges, “because the action the defendant was alleged to have committed never took place”, and ordered the paintings to be returned to him.

Both the civil and the criminal rulings were appealed. However, Giuseppe Zecchillo died in 2011 and the disputed works passed to his son Graziano, which brought the criminal appeal process to an immediate end. Graziano Zecchillo and the Manzoni Foundation then made a joint application to the civil court for the civil verdict of 2006 to be passed into judgment, thereby ending the civil appeal process as well.

Achrome (1960) by Piero Manzoni in Christie's London sale of Impressionist, Modern Art and Post-War contemporary art, 20 January 2010 Nils Jorgensen/REX/Shutterstoc

What do the verdicts mean?

The civil judge’s order that the works be destroyed and the criminal judge’s ruling that the paintings should be returned to their owner appear to be irreconcilable. In general, the civil and criminal systems in Italy run in parallel with no verdict superseding any other.

The Manzoni Foundation says it destroyed the works because it was ordered to do so by the civil judgment. “The criminal verdict does not prevail over the civil one,” says Rosalia Pasqualino di Marineo, Piero Manzoni’s niece, who serves as director of the organisation. Her view is reiterated by the foundation’s lawyer Alessandro Castellano.

However, Lionel Ceresi, who is involved in a separate, ongoing legal battle with the foundation, disputes this. “The criminal judgment in this case overrules the civil one,” he says, noting that the principle has been affirmed by Italy’s highest court, the Corte di Cassazione. Ceresi is calling on the foundation to disclose the terms of the agreement it has made with Graziano Zecchillo which has allowed it to destroy the contested works with no repercussions. (The foundation declined to comment on the matter and Graziano Zecchillo said in an email that he is unable to discuss the case.)

The Art Newspaper sent both the civil and criminal judgments to an independent criminal lawyer in Milan, Mauro Anetrini, who has no connection to either the Manzoni Foundation or the Zecchillo case. He noted that when defendants in Italian criminal trials are acquitted “because the action the defendant was alleged to have committed never took place”, as occurred in the trial of Giuseppe Zecchillo, then criminal verdicts “do affect” civil rulings. The owner of the paintings could be entitled to compensation from the foundation, he added.

But because Graziano Zecchillo has not continued with his civil appeal and has not initiated any new action against the foundation the matter is unlikely to be considered in court.

Where the courts decide

The Piero Manzoni Foundation says it has won 17 legal battles involving fakes in civil court and that, to date, it has destroyed 65 works, including Zecchillo’s. (It declined to disclose how many cases it has lost.) Although in Italy an artist’s heirs have the right to authenticate works (for a time after Manzoni died, his works were authenticated by his mother), if they then wish to destroy works which they believe to be fake, they must seek court approval—which accounts for the high number of authentication cases which end up in court in Italy. Judges have the power to dispute and overrule the artist’s heirs and kin.

Recent criminal rulings highlight the judiciary’s role in Italy as the ultimate arbiter in matters of authentication. Last May, a criminal judge in Milan issued a verdict in another case in which the Piero Manzoni Foundation had accused a Milanese collector, Matteo Tomasina, of being in possession of and trying to sell five fake works by the artist. The collector was acquitted.

In her ruling, the judge noted that “the fact that the… works are not included in the foundation’s official catalogues does not prove they are fake”, and that the foundation’s authentications are “just opinions, authoritative though they might be”. The foundation has not appealed this criminal verdict but says it will now seek to establish in civil court that Tomasina’s five works are fake.

Yet another ongoing criminal case has raised the issue of the foundation’s expertise and inherent conflict of interest in authenticating works.

At a hearing in October 2017, Lionel Ceresi, one of the lawyers representing the heirs of the art dealer Giovanni Schubert, asked the foundation’s director, Rosalia Pasqualino di Marineo, to identify the people responsible for making authentications at the foundation now that the art historian Germano Celant is no longer collaborating with the institution. Di Marineo said that since 2004 she has authenticated works in collaboration with the late artist’s siblings, Elena and Giuseppe Manzoni di Chiosca, who serve as president and vice-president of the organisation, respectively.

Ceresi told the court that “the people with a direct interest” in the outcome of authentications, because they themselves own works by Piero Manzoni, are now in charge of the process. Di Marineo rejected the suggestion that the foundation decrees work to be fake to increase the value of its own holdings. The market for Manzoni “needs a [plentiful] supply of works to function properly”, she told the court.

In a statement, Elena Manzoni di Chiosca and the foundation’s lawyer Alessandro Castellano said: “The foundation operates with a solid expertise born out of detailed and extensive study [of Manzoni’s works], the preparation of catalogues and exhibitions and the examination of hundreds of works over the course of many years… It [also] relies on [the advice of] art historians, graphologists and experts in materials.” It noted that it is self-evident that foundations give their qualified “opinions”, not “incontestable declarations”, and that “the final evaluation [of works] is the responsibility of the judiciary”.

When asked how many works by Piero Manzoni the foundation owns, Di Marineo said: “The family does not own many works and intends to sell as few as possible.” The foundation’s collaboration since 2017 with the international dealer Hauser & Wirth, she says, is not to sell works but to “increase knowledge of the artist amongst critics, collectors, institutions, the public, and also on the international market”.

“Together we are safeguarding the artist’s legacy by organising exhibitions and commissioning new scholarship and research that shed light on Piero Manzoni’s diverse practice… The Fondazione, helmed by Rosalia Pasqualino di Marineo, is the worldwide expert on Manzoni and has ultimate responsibility in executing the interests of the artist and his family,” Hauser & Wirth said in a statement.