William Tsiaras has a good eye—a trait that serves him well as both an ophthalmologist and an influential photography collector, who has quietly donated hundreds of works to museums over the years. His latest gift is to his undergraduate alma mater’s Colby College Museum of Art in Maine of more than 500 photographs from his personal collection, built over the past 25 years alongside the works he would acquire for institutions. As a board member and former chair, “he really put the idea on the table that the museum needed to have a collection of photography,” says the Colby Museum’s director Jacqueline Terrassa, adding that Tsiaras’s involvement with funding for purchases and matching gifts, starting in the early 2000s under former director Sharon Corwin, “transformed the whole collection”.

Tsiaras was born in Thessaly, Greece but came to the US as a child, where his brothers, two of whom are artists themselves, were born. He credits his interest in photography to one of the first purchases his father made when his family emigrated here: a Zeiss Ikon 35 mm camera. “I can remember it was ubiquitous, really part of our lives, it was everywhere we went,” Tsiaras says. “And then as soon as we became a little bit older, my father gave us all a camera—and it wasn't just a Brownie Instamatic. He loved German cameras, and he was a barber and he would purchase these magnificent cameras from customers and he gave us all one.” These gifts led two of his brothers, Alexander and Philip, to take up the medium as a career, becoming “card-carrying artists”, although Tsiaras himself is also an amateur urban landscape painter, taking photographs as reference images. “When we would go someplace, my wife constantly said, ‘Why aren't you taking pictures of the kids? Why aren't you taking pictures of us?’ Because I would always take pictures of things and places or things that I ultimately would want to paint,” he says. “It's always been a part of my DNA. For me, images and the visual aspect of everything is so important.”

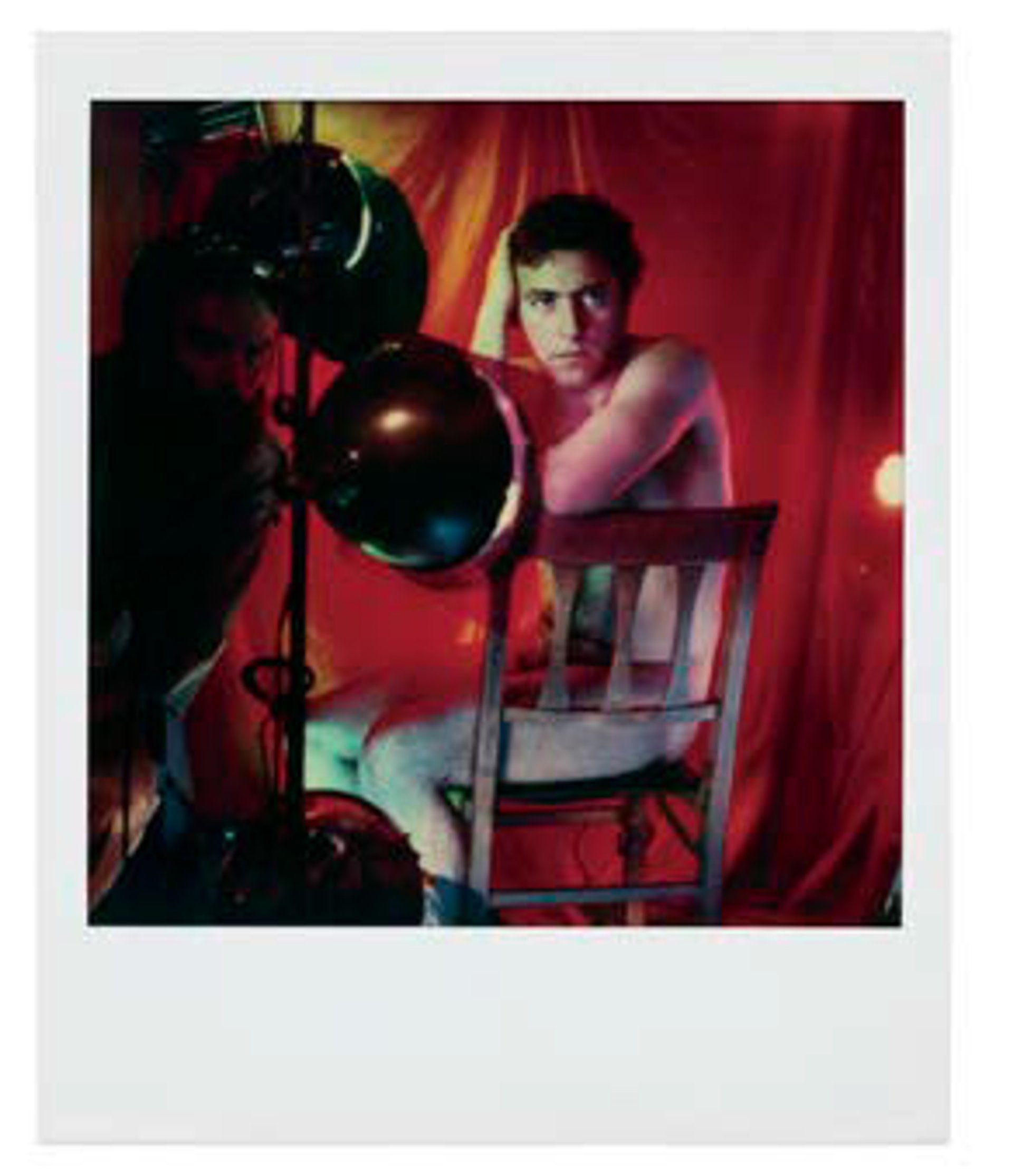

Memento Polaroid given to the collector William Tsiaras by Lucas Samaras after he posed for the artist's Sittings series, around 1978

It was through his brother Philip that Tsiaras first became involved in the art world during the 1970s, when he was introduced to the artist Lucas Samaras, who remains a close friend. “I met Lucas while I was still a resident at the University of Pennsylvania with a wife and young children, and started sitting for him for his early Polaroid series,” Tsiaras says. “I've purchased a lot of his work basically to donate to museums, and I've kept some for myself. That's when I really got interested in art.” Through Samaras, Tsiaras met other artists, such as George Segal, and Chuck Close. “After an opening, there'd be a big party at his apartment. I'd be sitting there talking to Jasper Johns and once the artists found out that I was an ophthalmologist, I was the hottest guy in the room. They would ask me about perspective and, ‘Why, when I looked down, do I see this and what happens?’ I would hang out with all of these guys who were much more interested in what I did than what they did.”

Later on, when he went to teach medicine at Brown University in Providence, where he still practices, one of his very first patients was the photographer Aaron Siskind. “We really hit it off, we became very close friends, so that I would spend a lot of time with him,” Tsiaras says, adding that Siskind introduced him to Harry Callahan, who established the photography department at the Rhode Island School of Design. It was through that friendship that Tsiaras became involved in the museum board at RISD and made his first major purchase as a collector, acquiring a large part of a 1994 solo show of Callahan’s work at the David Winton Bell Gallery at Brown University to donate back to the school.

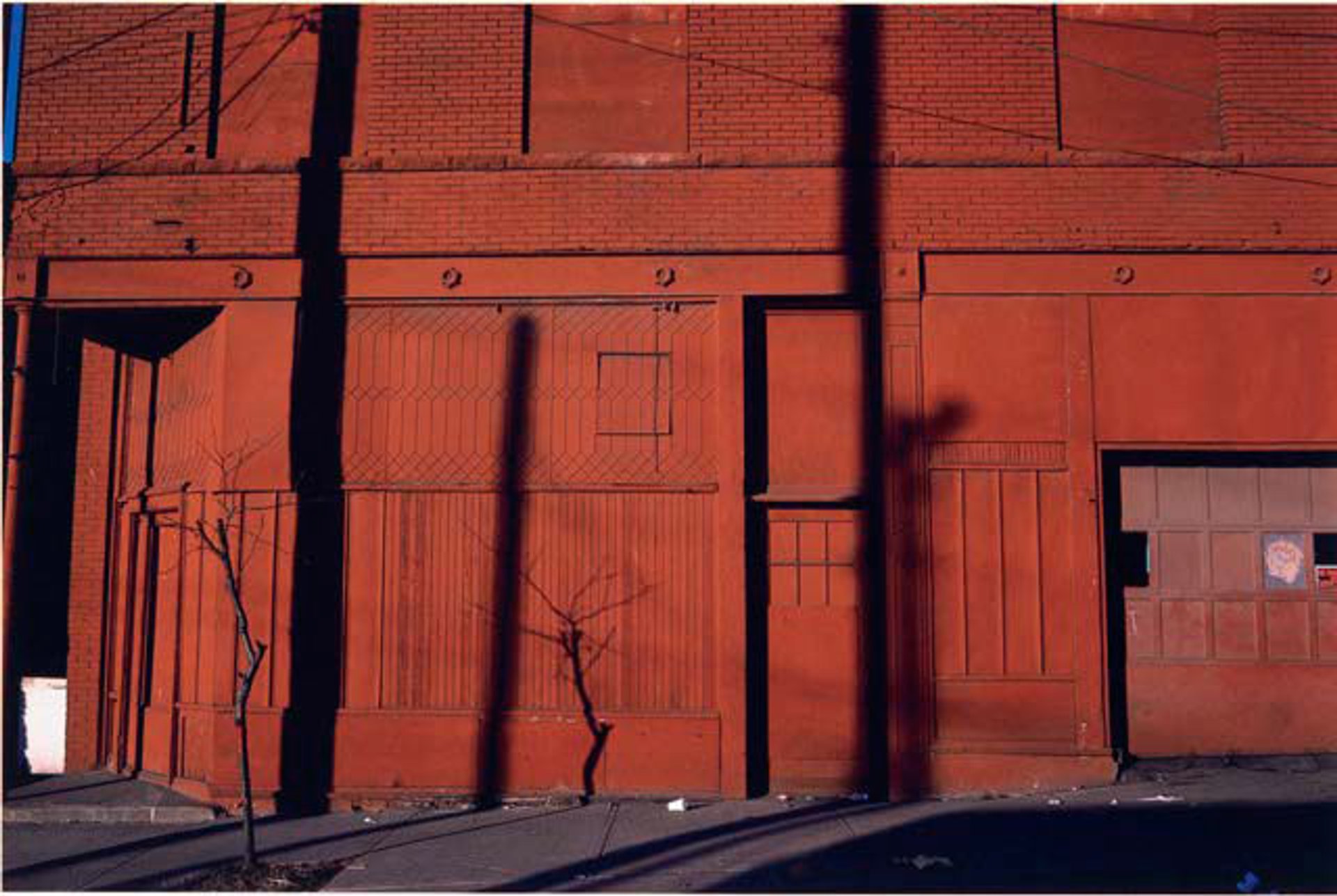

Harry Callahan, Kansas City (1981) The Tsiaras Family Photography Collection

“Harry wanted the series to stay in Providence because of the time he had spent at RISD. And so he said he would basically offer a sweetheart deal: if people would purchase a portion of the show to donate to Brown, he would give them a discounted price. And then whatever we spent for those photographs, we could go to New York and use that same amount of money to pick out an equal amount of photographs from his gallery Pace/MacGill,” Tsiaras explains. “ I had no money, I'm a young resident with a young family starting a practice in a new place, but it seemed to me that this was bizarre. Why wouldn't everybody do that? I mean, basically you're getting an equal amount of photographs of your choice. Two other people did it—one was the president of Bank of America and another was a relatively well-off person— and then me, who went and borrowed money to buy a third of that show.”

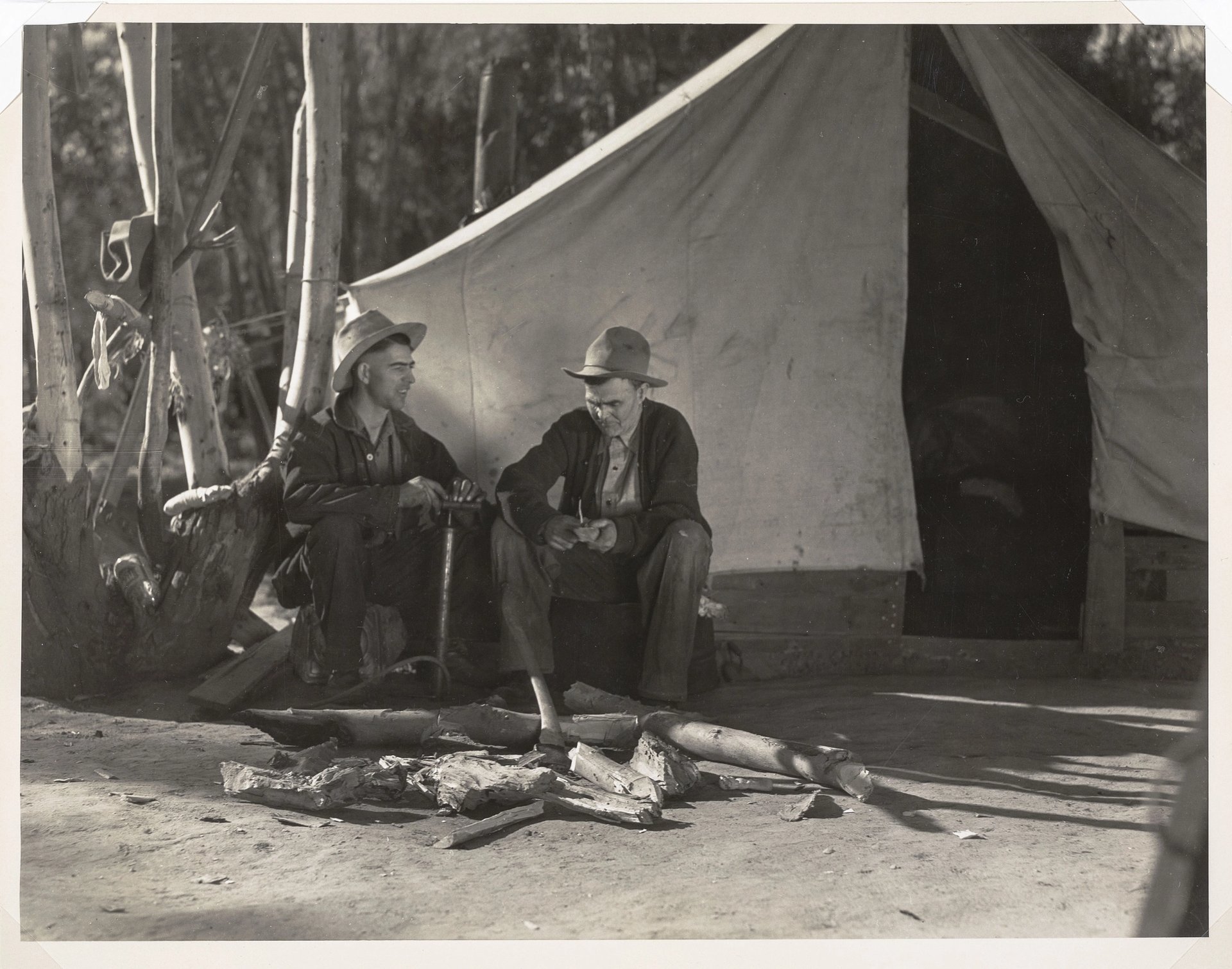

“My wife thought I was crazy, everybody thought I was crazy, but I thought it was just a great thing to do,” Tsiaras adds. “After I paid off that debt, I said to my wife: ‘This is a win-win situation where we're helping the artists, we're helping the institutions, and it's just fun. So right after I decided I'd do a matching gift to Colby. As a result of that, over the past 40 years, Nancy and I have basically donated photography to every major institution in America, from the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, to the Art Institute of Chicago, to the Museum of Fine Arts Boston.” At the same time, while he was acquiring dozens of works for museums, Tsiaras was also purchasing one or two for his own collection, gathering more than 500 pieces over the decades. In recent years, when he and his wife decided to make a family gift to Colby, he started filling in some gaps based on his personal interests, for example buying pieces by many of the member of the Photo League, such as David Vestal, Morris Engel, Arthur Leipzig, Helen Levitt, Sol Libsohn, and Walter Rosenblum. The collection also holds examples by historic figures, Ansel Adamns, Berenice Abbott, Edward Steichen, Imogen Cunningham, James Van Der Zee, Dorothea Lange, Helen Levitt, and Roy DeCarava, as well as contemporary artists, including Lauren Greenfield, Scott Alario, Pedro Abascal and Lissette Solórzano.

Dorothea Lange, Squatters' camp on highway. Characters in scene from Resettlement film. Near Bakersfield, California (1935) The Tsiaras Family Photography Collection

The breadth of the collection will allow Colby to use the works as a teaching tool, not just for photography students but across its programmes. “Colby's pedagogy truly embraces the arts as part of an absolutely interdisciplinary approach to teaching and learning,” Terrassa says. ”The collection is used in courses from economics to meteorology, to literature, to dance, to of course, the visual arts.” For example, works by the Cuban photographer Alejandro González from his series Improper Behavior, in which he was making a statement against homophobia by depicting ordinary people whose sexual preferences had put them on the margins of Cuban society, Terrassa explains, could be used in classes on gender studies and sexuality. “That is actually one of our collection criteria: how can this be used across the curriculum?” she adds. “And will it be used—is it going to be just sitting in storage or are we actually going to use it?”

In addition to using the photographs in course work, a catalogue was published by the school this past fall, titled Act of Sight: The Tsiaras Family Photography Collection, ahead of a planned exhibition that has been postponed until 2022 because of the coronavirus.

But while this gift is the culmination of years of patronage, Tsiaras does not see it as the end of his photography collecting. “My sweet wife says that basically I have a collector's gene. It's something that is very, very difficult to stop doing,” he says. “If I see a young photographer whose work I just love, I'll basically try to do what I've done all along. Why stop? I would probably give the work to someplace that I think it could go—and probably buy a photograph or two for myself that I can add on to the collection at Colby.”