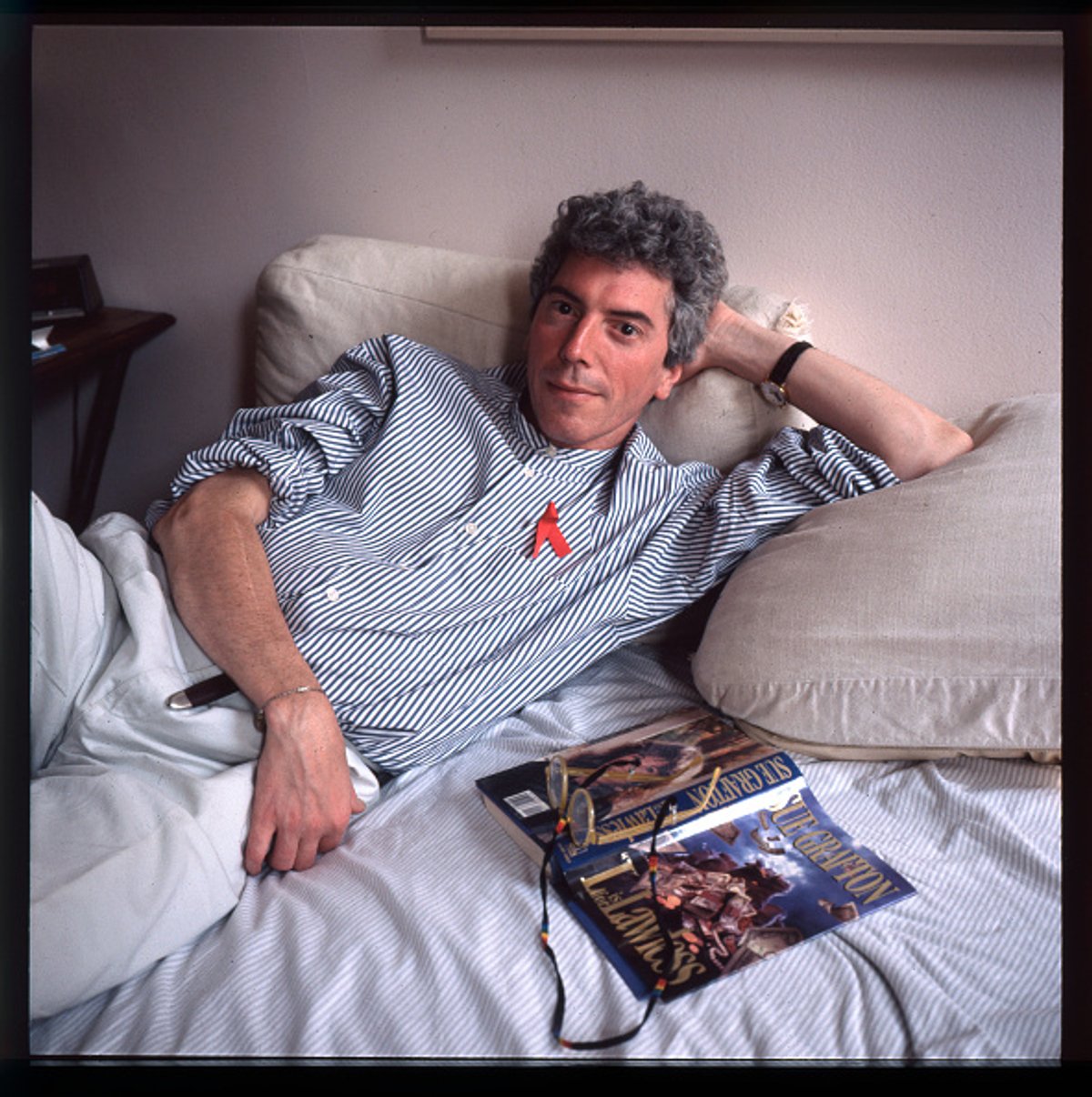

Patrick O'Connell, the founding director of the organisation Visual Aids, which since the late 1980s has used the arts to raise awareness about HIV and Aisa and to support artists living with the disease, has died, aged 67. Perhaps the most recognisable of the many projects that O’Connell helped develop is the red Aids ribbon, which was first distributed and worn by activists and supporters in 1991. O’Connell died in a hospital in New York City on 23 March from complications due to Aids, after 40 years of living with the disease, his brother Barry confirmed to The New York Times.

Born in New York City in 1953, O’Connell’s studied history at Trinity College before pursuing a career in the arts. He became the director of Hallwalls Contemporary Arts Center in Buffalo but held the position for only about a year before returning to Manhattan to work at Artists Space, the now-legendary downtown arts venue that at the time was the breeding ground for the Pictures Generation.

By 1988, the seeds had been planted for what became Visual Aids. “We’re an odd organization in terms of the history and the model we used,” O’Connell told the publication POZ. “A number of us were meeting constantly at memorial services and funerals, and the conversation started revolving around the impact Aids has had on the arts. A core group started meeting very informally on a monthly basis.” By that point, O’Connell had already been diagnosed as HIV positive.

Inspired by the Vietnam Moratorium—a 1969 nationwide day of protests against the Vietnam War—Visual Aids carried out the first “Day Without Art” in 1989. The original plan had been for museums and galleries to all synchronously close for one day, but as it became clear organising this would be impossible, another demonstration was devised. On 1 December 1989, over 800 museums and galleries responded to the call for “mourning and action in response to the Aids crisis” by shrouding paintings and sculptures in fabric. The Metropolitan Museum of Art chose to take Picasso’s 1906 Portrait of Gertrude Stein off the wall and replace it for the day with a placard containing information about Aids and HIV. “Day Without Art” has continued annually since. “It was very exciting,” O’Connell said in his interview with POZ. “The enormous success of that first ‘Day Without Art’ in 1989 forced us to reassess whether we would be an informal collective doing projects or we were going to become an organization.”

The Red Ribbon Project, which O’Connell referred to as a “public participatory artwork”, began when he gathered artists, friends, and colleagues to cut and fold thousands upon thousands of snips of ribbon. O’Connell’s goal was to have the symbols worn by celebrities at that year’s Tony Awards—and it worked. After their appearance at the highly watched theatrical event, the ribbon became a ubiquitous sign of both protest and awareness—The New York Times dubbed it “the year of the ribbon”—although for some it was seen as an easy gesture when more strident action was needed. “People want to say something, not necessarily with anger and confrontation all the time,” O'Connell said of the ribbons. “This allows them. And even if it is only an easy first step, that's great with me. It won't be their last."