Syrian artists, including Jumaa Nazhan, the only artist known to have worked secretly in an Islamic State (IS)-controlled area, are the focus of a new gallery in London’s Mayfair. The Stories Art Gallery, which opened in October, champions artists who take a non-political approach in their work to challenge violent stereotypes of the county.

Trained at the Institute of Fine Arts in Damascus, Nazhan was working as an art teacher at a school in Deir al-Zour when the town was occupied by IS in Syria’s civil war. “In the first year, IS allowed people to work, to go to school and get salaries. Then they became stronger, and schools were closed; only Islamic schools were allowed,” Nazhan says. The artist smuggled around 30 works out of the IS-controlled area of Deir al-Zour to a gallery in Damascus in order to raise money. “I was determined, because I wanted to continue to live,” he says.

In 2015, he escaped to Damascus with his family. If he had been caught, he says: “I think I would have been beheaded because I was focusing on minarets and churches” from an area that had a significant Armenian Christian population. “If they had seen a cross I would have been [killed].”

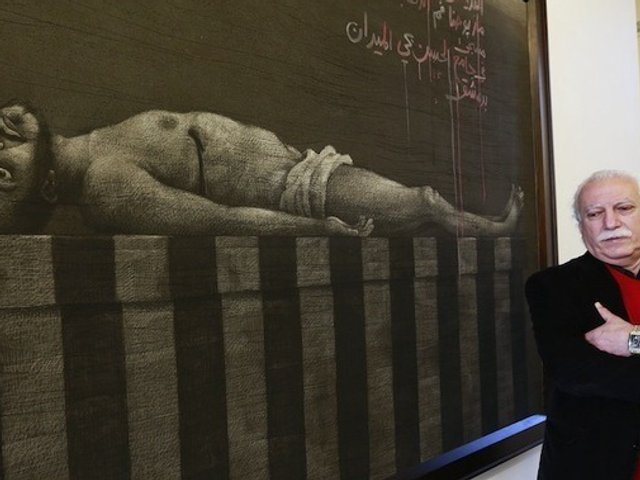

Nazhan’s works are mostly abstracted townscapes. Under IS, he worked on cardboard coated with acrylic and glue, mostly in black and white. Only in the safety of Damascus did he start to use colour again. “He is inspired by Klimt but he has his own style,” says Manas Ghanem, the director of Stories Art Gallery. Ghanem’s own collection includes several works by the artist, which she hopes will be acquired by a museum.

Before opening her gallery, Syrian-born Ghanem was a lawyer who worked across the Middle East and North Africa with the United Nations High Commission for Refugees and the UN children’s agency Unicef. The gallery occupies the ground floor of a Middle Eastern real estate company but hopes to expand into the building’s generous basement for an industrial feel. The project emerged from a Syrian exhibition that Ghanem staged in Greece, where she last worked for Unicef.

“As a Syrian I am a refugee myself. I live in the UK, my family is back in Syria, but I have family all over,” she says. “We decided to create an opportunity for artists who were unable to present their work in public and to also show that Syrians cannot be reduced to victims, refugees or migrants,” she says. Ghanem is also an associate of the Centre for Resolution of Intractable Conflict at Oxford University.

“We picked a number of artists who continued to produce good works throughout the years of the crisis. We selected pieces that portrayed a significant message of love and peace and hope for the future. They used beautiful colours rather than grey, images that are beautiful rather than the main images of pain and death.”

The gallery’s roster is not limited to Syrian artists. In November it exhibited works by Elli Chrysidou, a Greek artist who is also deputy mayor of Thessaloniki, with paintings playing with the image of Albrecht Dürer’s famous rhinoceros. But it will continue to focus on showing artists who “went through hell yet were able to produce something very inspiring”, Ghanem says.

Artists due to go on show in December include Edward Shahda, Nizar Sabour and Bassem Dahdouh, veterans of Syria’s domestic art scene who have also shown internationally. “We want to see something that people associate with respect rather than pity, feeling inspired rather than saturated by mainstream images and thoughts,” Ghanem says.