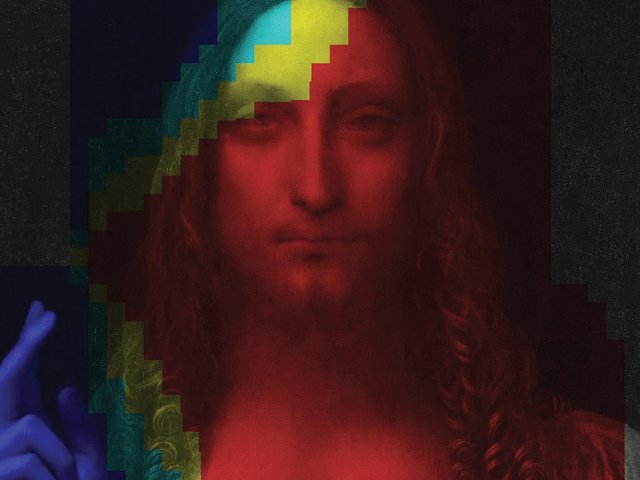

Leonardo’s Salvator Mundi has become so notorious and so controversial—due to its £450m price tag, its fiercely debated autograph status, and its mysterious disappearance—that the publication of a long-awaited academic book by three of the key protagonists in the saga is newsworthy in itself.

Delayed for several years, the book by Robert B. Simon (one of two discoverers of the painting and the earlier owner), Martin Kemp (a Leonardo expert and champion of the attribution) and Margaret Dalivalle (a provenance scholar) will be published by Oxford University Press to coincide with the opening of the Louvre’s Leonardo exhibition on the 24 October (where the Salvator Mundi is unlikely to appear). The publisher has given The Art Newspaper an advance proof of the book.

The book’s introduction is candid about its consideration of only three facets of the story: “as with an opera having a grand and intricate plot” it has “necessarily bypass[ed] many ancillary issues”. These many omissions include the “fractious issues” surrounding a previous Sotheby’s private sale (2013) and an on-going legal battle; Christie’s 2017 sale and its grandiloquent marketing campaign based partly on the National Gallery’s curatorial assessment of the picture (key elements of which are contradicted in this book); and the Saudi Arabian purchase of the painting, alluded to in Kemp’s Epilogue, with a mention of the “scarcely credible” price of $450m.

Another prominent protagonist, Nicholas Penny—who, when director of the National Gallery in London, stuck his neck out along with the curator Luke Syson by including the newly discovered and much restored painting as an autograph Leonardo in the gallery’s 2011 Leonardo exhibition—is commended for bravery in the acknowledgements. Simon relates that when Penny came to see the painting in New York in 2007 (while serving as senior director of sculpture at the National Gallery of Washington) it took him “only a nanosecond … to understand what he was looking at”. A few months later, when he became director of London’s National Gallery, Penny offered to share the painting with scholars in a spirit of scholarly enquiry on “neutral ground” in Penny’s words, although he also advised Simon to show it to the Metropolitan Museum in New York, as Simon’s “home institution”. There, it was examined by the Met’s Leonardo expert, Carmen Bambach, among others.

The National Gallery’s subsequent convening of experts—including Bambach from the Met—forms the next chapter in the story. Ben Lewis, in his recent book on the Salvator Mundi, has hotly disputed the National Gallery’s account of the academic consensus reached at this meeting, that the picture was by Leonardo himself and not a product of his studio. But Simon firmly reiterates here that Penny phoned him “to tell me that that the sought-after consensus had in fact been achieved”. This Simon says gave him confidence “that the cautious prefix ‘attributed to’ must be deleted from future descriptions of the painting.”

Yet some important assertions made by Syson in the 2011 exhibition catalogue are overturned in the book. While the National Gallery dated the picture to 1500, for what—it is strongly implied in the book—were expedient reasons (to do with the scope of their exhibition), Kemp now concurs more with Frank Zöllner’s later date of around 1507 onwards (cited in the latter’s 2017/2018 monograph). Dalivalle can also find no direct record of the Salvator Mundi in any French royal collection; she thinks it is unlikely that it was commissioned by the French King, Louis XII, as was confidently mooted in the National Gallery catalogue and more decisively in the Christies’ sale literature; the supposed French royal provenance may even have played a part in the painting being acquired for the Louvre Abu Dhabi. Elsewhere in the book Kemp cites Pope Leo X as “a particularly attractive possibility” for the picture’s patron. Dalivalle confesses that “we simply do not know where it went” after 1530, before it turned up at the court of Charles I. And in her fastidious account of the picture’s fortunes at the Stuart court she confesses “provenance histories are fallible, malleable and subject to radical revision”: a useful caveat.

The book is also candid about some of the restorer Dianne Modestini’s more controversial decisions: to mask a first thumb in favour of a second thumb that the artist subsequently painted, together with an original arabesque pattern in the crossed bands of Christ costume, and to reconsider her decision to leave the later muddy grey background intact because of a lack of original paint in the background (she repainted the background black having found traces of black paint, but also inspired by the London version of the Virgin of the Rocks). All this was done in order to make it “a viable work of art,” Simon says. Modestini also provided “a resolution of Christ’s eyes”. (Modestini has just published a website illustrating her investigations and interventions: salvatormundirevisited.com).

Kemp’s detailed account, of the genesis of this “icon” and its visual characteristics focuses at length on Leonardo’s optical effects (the globe and the differences in focus between the blessing hand and the head), but he also attempts to make a virtue out of any criticisms made by the painting’s detractors: the blue robe (instead of the red robe that Leonardo’s Christ wears in The Last Supper, and which is worn by the Salvator Mundi variants) is due to the artistic choice of precious ultramarine (albeit of a particularly low grade) and its ability “to highlight any surface lustres on the crystal sphere that Christ holds”; the fact that Vasari in his Life of Leonardo (1550) says that Leonardo “went as far as to assert that the head of Christ [in his Last Supper] was left unfinished since he did not think it was possible to convey the celestial divinity required for Christ”, Kemp infers it does not suggest a reluctance to portray Christ; “Better,” he says, to say that “Christ was left formally and emotionally indefinite”; and he notes that the two Leonardo Salvator Mundi drapery studies in Windsor are on a larger scale than is the norm and are not precisely paralleled in Leonardo’s other drawings, though goes on to cite some exceptions in favour of Leonardo’s authorship.

And as for the beard, which is standard in images of the Salvator Mundi and is present in all the copies bar one (there are 27 known to date), but is not evident in this definitive version, Kemp says that there is a “decent possibility that there was once a very fine and sparse beard in the picture before it was abraded … as if breathed onto the surface, rather than painted.” This, however, is contradicted by Modestini’s findings: she is categorical on her website that there is no physical evidence of the remains of a beard or any facial hair, accounting for Christ’s “disquieting, androgynous appearance”. Sloppily executed elements—such as the mistake in the interlaced knot design on the crossed bands, or the clumsy folds at the top of the robe—are errors that Kemp attributes to an assistant. The looped knot design in the under-drawing could he says be used to support a hypothesis that the painting was begun in Milan “but this seems to complicate things unnecessarily”.

As regards the possible role of studio assistants or pupils, harsh words are reserved for Bambach, who, as we have seen, played a key role in various episodes of the saga. In Kemp’s epilogue he notes that Bambach, in her recent three-volume monograph Leonardo Rediscovered, repeats her attribution of the picture to Boltraffio, with some scattered interventions by Leonardo. “We are confident”, Kemp says, “that the full review we have provided will serve to undermine what seems to be an arbitrary judgement.” But perhaps the unkindest cut of all is to relegate Lewis’s recent book on the Salvator Mundi to a single footnote (and a listing in the bibliography), citing it as an example of sensationalist journalism.

• Leonardo’s Salvator Mundi & the Collecting of Leonardo in Stuart Courts by Martin Kemp, Robert B. Simon and Margaret Dalivalle is published by Oxford University Press on 24 October 2019