Minutes before lawyers for the drug company Purdue Pharma argued for the dissolution of their company in bankruptcy court, the photographer Nan Goldin picked up her dogged pursuit of the opioid manufacturer from the steps of the Southern District Federal Courthouse in White Plains, New York. “Artists need to step up and put their bodies on the line,” Goldin told The Art Newspaper. “It’s not going to hurt their careers. And in this day and age, a career is not as important as fighting these systems.”

During the protest, Goldin and 15 activists from the groups PAIN (Prescription Addiction Intervention Now) and Truth Pharm tossed blood-soaked dollar bills into the air to represent the billions in profits that Purdue and the Sacklers have made from the sale of painkillers over the last two decades. The fake banknotes featured the slogan “In Pharmacy We Trust”, an image of the Purdue headquarters and the number 400,000—the amount of people who have died from opioid overdoses between 1999 and 2017, according to the CDC. Pill bottles scattered on the court steps contained similar information and a warning label—“Side effect: Death.”

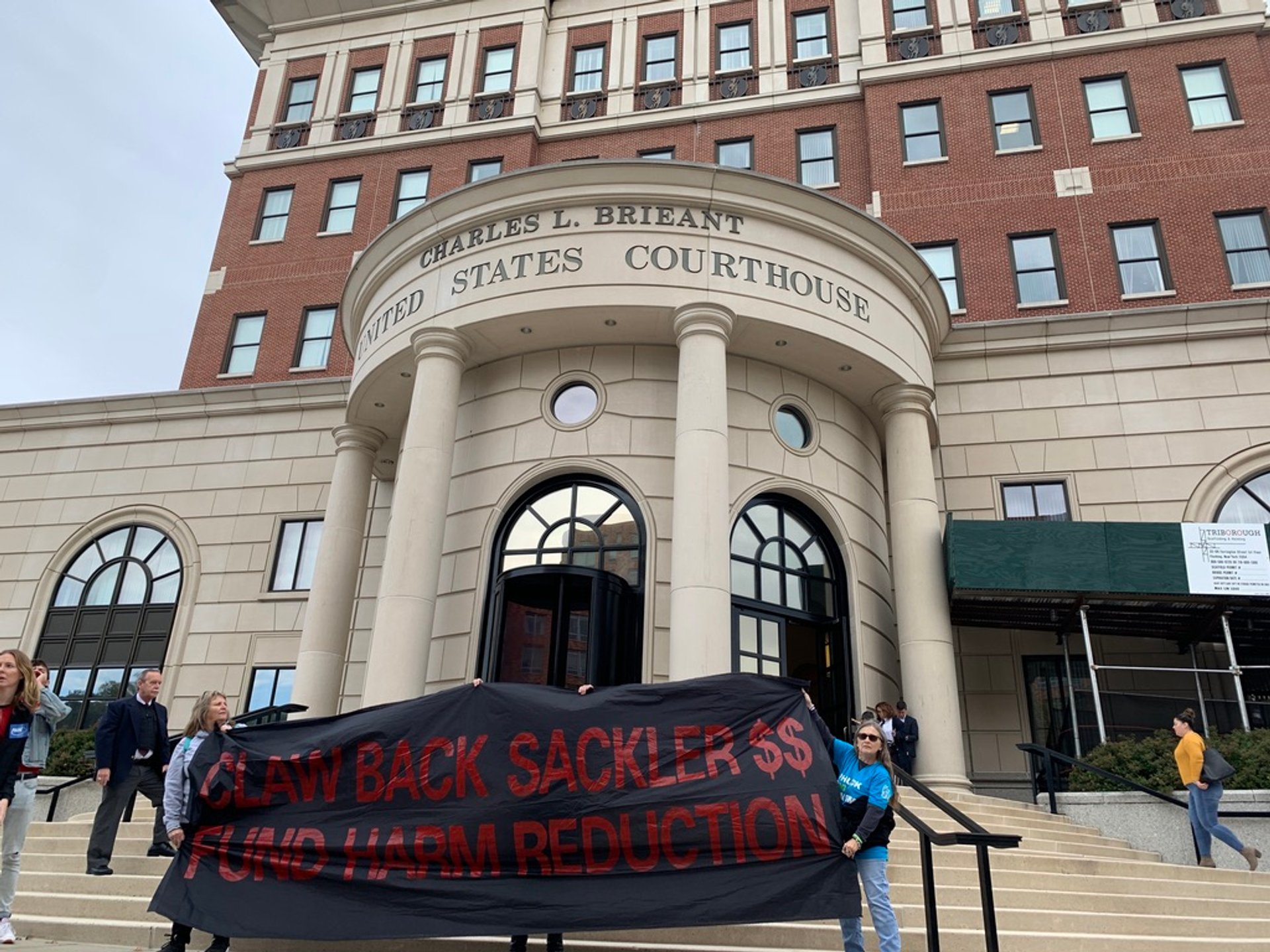

The demonstrators also unfurled banners demanding that courts “claw back” money from the pharmaceutical company and the personal fortunes of the Sackler family members who profited from it, to fund harm reduction programmes that have been shown to decrease overdose deaths.

Inside the courtroom, Judge Robert Drain was listening to Purdue Pharma’s bankruptcy case, which critics have characterised as a way to shield billions in opioid profits from the more than 1,600 lawsuits brought by state and local government against the drug maker, and let the family behind the company absolve themselves from responsibility for the US opioid crisis. Under Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection, Purdue would be able to pause all litigation against its assets. The company’s transformation would be overseen by a bankruptcy judge and the appointment of new trustees and a board free of the Sacklers. It is unclear, however, whether the settlement would exempt family members from pending litigation against them individually.

The demonstrators unfurled banners demanding that courts “claw back” money from the pharmaceutical company and the personal fortunes of the Sackler family members who profited from it, to fund harm reduction programmes that have been shown to decrease overdose deaths Photo: Zachary Small

“We think the settlement currently being negotiated in court is a lot of smoke and mirrors,” says the artist Marina Berio, a member of PAIN member and a longtime friend of Goldin’s.

In September, the New York attorney general’s office said that it had tracked nearly $1bn in wire transfers from Purdue to Sackler family members through Swiss bank accounts. “While the Sacklers continue to lowball victims and skirt a responsible settlement, we refuse to allow the family to misuse the courts in an effort to shield their financial misconduct,” Attorney General Letitia James said in a statement. New York, New Jersey, and Connecticut have so far refused to join a tentative $10bn settlement with the OxyContin maker. Those states would like to see the Sacklers commit at least $4.5bn of their personal wealth to families affected by the crisis. Currently, the Sacklers have agreed to provide a $3bn payout over seven years.

The company maintains that bankruptcy proceedings will clear a path for one of the biggest corporate payouts in American history. Several lawyers for the pharmaceutical giant stressed in their statements to the judge that the corporation has always manifested financial transparency in their actions.

For more than a year, PAIN has sustained a two-pronged assault on the Sackler family’s reputation. Demonstrators have simultaneously urged the art world to divest itself from the philanthropic billionaire dynasty while lobbying public officials to hold individuals Sacklers liable for the opioid crisis. The Guggenheim Museum, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, London’s National Gallery, the Tate, and others have announced that they will not accept any more Sackler money.

The Center for Disease Control (CDC) estimates that more than 70,000 Americans died from drug overdoses in 2017. Goldin, who previously struggled with an addiction to painkillers, has used her platform to publicise the severity of the opioid crisis and a need to hold Purdue and its owners, the Sackler family, accountable. She has also repeatedly encouraged New York Governor Andrew Cuomo to open overdose prevention centers across the state. “This is a major health crisis,” Berio said. “There are a lot of reasons to be involved. I saw Nan through her last detox and rehab. I’ve also lost some students to overdoses over the years.”

As the latest protest in White Plains started, a local resident named Peggy came over to watch the demonstration unfold. She has struggled with opioid addiction herself, having first taken OxyContin after a doctor prescribed it for her back pain. “I became an addict overnight,” she said, “I couldn’t wait to leave work and come home so that I could take more pills.” While Peggy told us her story, activists on the courthouse steps continued chanting: “Not one more. Not one more.”