While it waits to open its doors, the new Norwegian National Museum has put its collection on ice. It has placed a digital copy of its entire collection of some 400,000 objects in the Arctic World Archive (AWA), which is cocooned in a coal mine burrowed into a mountain of permafrost on the Arctic archipelago of Svalbard.

The AWA was established in 2017 by the Norwegian technology company Piql AS as a “safe repository for world memory”. The site, near the Svalbard Seed Vault, aims to secure digital artefacts and information of world importance from the dangers of natural disasters, technological changes, hacking and wars.

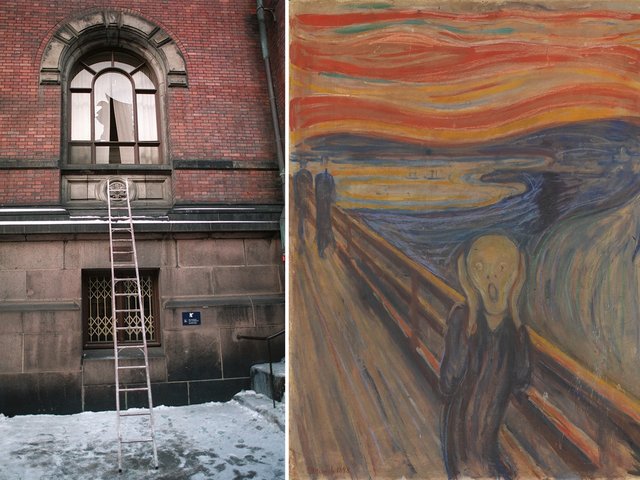

Photographs of the museum’s collection, covering fine art (including Munch’s The Scream) and works of architecture and design, have been transferred to “piqlFilm”: analogue film that can retain digital data and keep it safe offline. The AWA calls the medium “futureproof”. In theory “the only thing you need to read the film is light,” says Rolf Yngve Uggen, the museum’s director of collections management.

The museum has made three deposits of digitised works of art for an undisclosed fee, which now sit alongside consignments from Unicef, Sweden’s Moderna Museet and the Vatican Library. The AWA claims it can keep their data alive for “over 1,000 years”.

The subterranean safekeeping of artefacts and records is nothing new, however. During the Second World War, the National Gallery in London consigned its treasures to Manod Quarry in Wales. But Svalbard is particularly remote and secure. “It’s like being on another planet,” Uggen says. “It’s like the final frontier.”