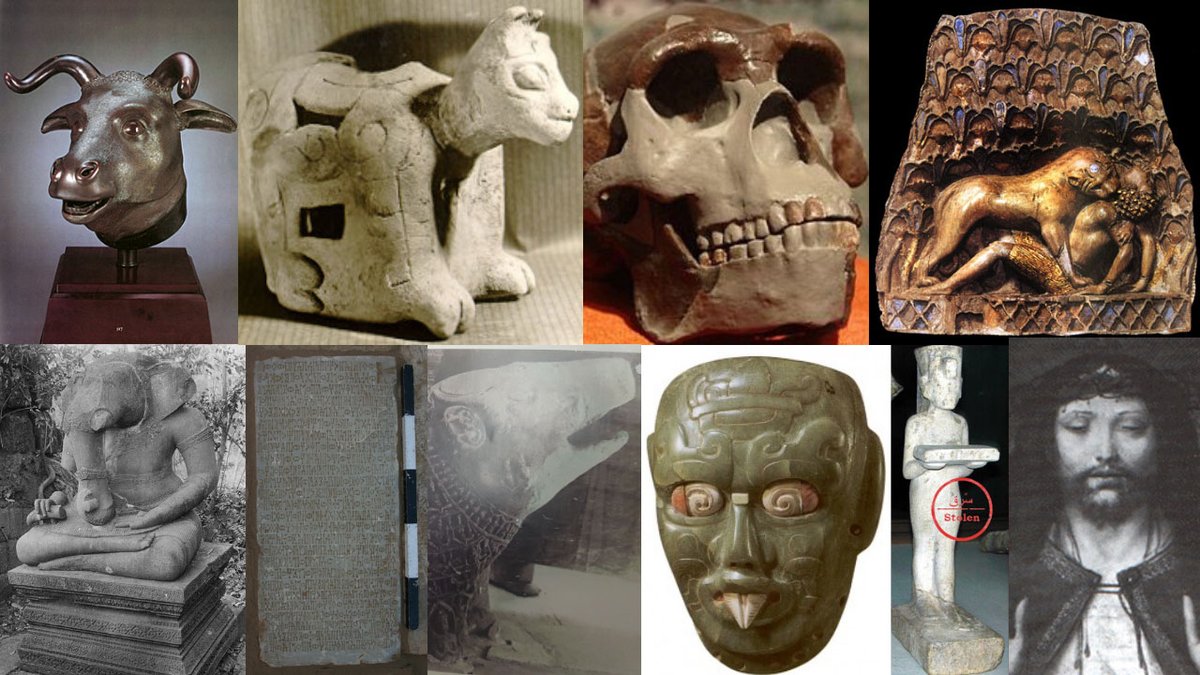

A Mesopotamian ivory relief stolen from the Iraq Museum in Baghdad during the war in 2003; a statue of Ganesh snatched by the Khmer Rouge from the Koh Ker temple complex in Cambodia in the 1970s; a painted icon of Jesus Christ crowned with thorns pillaged from Emperor Tewodoros’ Mountain Fortress in Maqdala, Ethiopia, by a British expedition in 1868.

These and several other historic objects make up the Antiquities Coalition’s list of the “Ten Most Wanted Antiquities”, released today. “It was important, we believe, to highlight that there are still countless missing masterpieces in the world,” says Deborah Lehr, the chairman and co-founder of the Antiquities Coalition. “Given the impact of social media, we wanted to reach out to the general public to raise awareness about these missing antiquities and enlist their support in finding them.”

As a launching point, the organisation, in consultation with leading experts, archaeologists and law enforcement, decided to feature “infamous cases of cultural racketeering”, Lehr says, focusing on archaeological objects that are at least 250 years old. “Based on the feedback, we chose to use high-profile missing items from different parts of the world to illustrate how this is a global issue that requires a global and widespread response,” Lehr adds.

Among the works included on the top ten list are the “Peking Man” Homo erectus fossils, which inexplicably disappeared as they were being shipped from China to the US for safekeeping during the Second World War, and a green stone mask depicting the sun god Kinichi Ahua, taken from the Classic Mayan Río Azul site in Guatemala in the 1970s, which was last on view at the Barbier-Mueller Pre-Columbian Art Museum in Barcelona in 1999.

A Statue of Varaha, depicting the Hindu god Vishnu’s boar avatar, was violently removed from the Temple Complex in Atru, Rajasthan, India in 1988 by thieves who attached an iron chain around the sculpture to break it free from its base. The statue is linked to the antiquities dealer Vaman Ghiya, who was arrested by Indian authorities in 2003 and convicted of smuggling hundreds of thousands of looted objects out of the country but was later acquitted.

At the top of the list is an inscribed alabaster stone tablet, ripped from the floor of the Awam Temple in Marib, Yemen, sometime between 2009 and 2011. “Yemeni antiquities remain under critical threat due to the ongoing civil war and humanitarian crisis,” Lehr says, adding that a report issued by the Antiquities Coalition and Yemen last year showed that “more than 1,600 objects were missing just from the country’s museums due to looting”.

Lehr says it is important to note that when Yemen signed on to the 1970 Unesco Convention last September, it made an official request to the US for emergency import restrictions as well as a full memorandum of understanding (MOU) under the US Convention in Cultural Property Implementation Act. The US government announced that it would impose emergency import restrictions on certain archaeological and ethnological material from the Republic of Yemen in February that will remain in effect until 11 September 2024, but “a full bilateral MOU is still a work in progress, and is much needed”.

Yemen is among many countries whose heritage continues to be under threat, and illicit activities have only worsened since the coronavirus pandemic spread across the globe. “Looters are taking advantage of the pandemic to pillage ancient artefacts from archaeological ruins, while art thieves target masterpieces in metropolitan museums,” Lehr says. “While the coronavirus has largely shuttered above-board dealers, galleries and auction houses, the international black market stays wide open for business.”

Anyone with information on any of the objects including on the top ten list is encouraged to reach out to the Federal Bureau of Investigation, Interpol and Homeland Security Investigations, or to contact the Antiquities Coalition. The list will be updated if any items are found, and the coalition plans to highlight recommendations on leads that come in from experts as well as submissions from the public.

While many of the works have been missing for decades, Lehr says “there is always hope” that they will be recovered, and that “access to technology may bring up new leads”. She adds: “Social media allows us to reach out to the general public, who have shown great interest in this topic, and enlist their support to recover these missing treasures.”