It is striking how museum expansions are often experienced as a shock to the psyche—a sense that a familiar narrative has been jettisoned in favour of a creative leap off a cliff. But as the Museum of Modern Art in New York prepares to open its doors on 21 October after a $450m expansion and reinstallation, curators are casting the experience more as an absorbing adventure that will unfold for years to come.

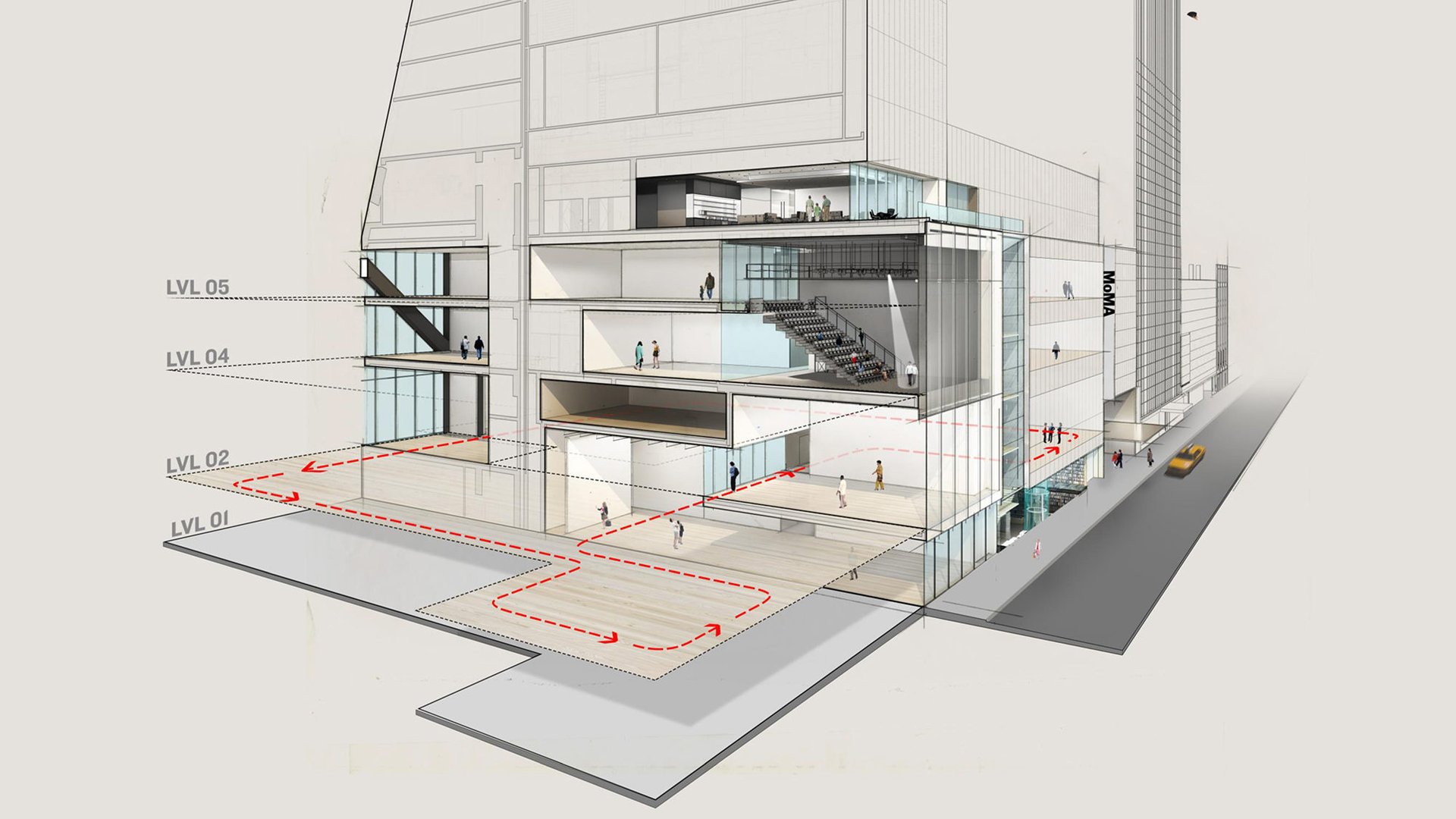

The museum’s costly expansion, ten years in the making and designed by the architects Diller, Scofidio + Renfro in collaboration with Gensler, carves out 47,000 additional sq. ft of space in which to recount the tale of Modern and contemporary art. MoMA’s pre-existing home is now connected to Jean Nouvel’s newly completed residential tower, with a new building sandwiched between the two; walls have been removed, staircases extended and ceilings lifted as existing permanent collection galleries have been refashioned to flow seamlessly into new ones.

A rendering of the Museum of Modern Art's westward expansion, with the added space outlined in red © 2017 Diller, Scofidio + Renfro

For Ann Temkin, it was clear from the moment she became MoMA’s chief curator of painting and sculpture in 2008 that no expansion would ever allow the museum to truly demonstrate the riches of its unrivalled Modern and contemporary collection. “If you can’t address it with space,” went her thinking, “the other resource you have is time.”

Thus was born the idea of the perpetual rehang: much of what visitors will see when they re-enter the permanent galleries on 21 October will change in six to nine months as curators swap out works in regular rotations. (Checklists for next May’s rotation are already drawn up.)

We didn’t want a jumble, where the beauty of each individual medium is somehow compromised

What curators have installed for now is a rethinking of the Modernist canon. In a top-to-bottom transformation, they have abandoned the museum’s formerly confident story of the major "isms", from Post-Impressionism to Cubism to Surrealism to Abstract Expressionism. Works from different movements and continents now jostle in the same space.

What is more, the museum has collapsed the old divides between paintings and sculpture, drawings and prints, architecture, design and photography: the permanent collection galleries now present works from across all disciplines in a generally consistent chronology from the late 19th century to the present day, with some time travellers thrown in.

See inside the newly expanded MoMA

The two opening galleries in particular attest to the new approach. Viewed as a unit, they demonstrate how mixing mediums can have a resounding impact—more powerful, Temkin says, than she and her colleagues had imagined.

If Gallery 501 enshrines the Post-Impressionists who have generally populated Modernism’s origins story—Van Gogh’s Starry Night, Cézanne’s The Bather and The Boy in a Red Vest, selections of Vuillard and Seurat—it is the judiciously chosen unexpected works that throw them into relief. “We didn’t want a jumble, where the beauty of each individual medium is somehow compromised,” says Temkin.

A view of MoMA's reconfigured Gallery 501, with pottery by the Mississippian artist George Ohr (1857-1918) displayed with European paintings Jonathan Muzikar/© Museum of Modern Art

Earthenware vessels by the Mississippi artist George Ohr (1857-1918) echo the sculptural forms of Cézanne's Chateau Noir (1903-04) and The Bather (around 1885). An intriguing 1882 charcoal drawing by Odilon Redon of a hot-air balloon shaped like an eye makes you look twice at Gauguin’s deeply strange 1889 Portrait of Meijer de Haan, with its flat colours and bulbous Baconesque head.

But before you have delved into all these details, you catch a glimpse of Gallery 502 through the door to your right—a Salon-style display of turn-of-the-century photography and film. “I love the idea that Picasso and Braque went to the movies and Cubism was born,” says Rajendra Roy, MoMA’s chief curator of film, “but film was also doing important things that had nothing to do with how it influenced other artists.” To wit: the until-now-unseen, newly restored footage shot from a New York subway car in 1905 by the American Mutoscope and Biograph Company.

MoMA's Gallery 502, where newly restored footage shot in 1905 in the New York subway system is on view © Jonathan Muzikar/Museum of Modern Art

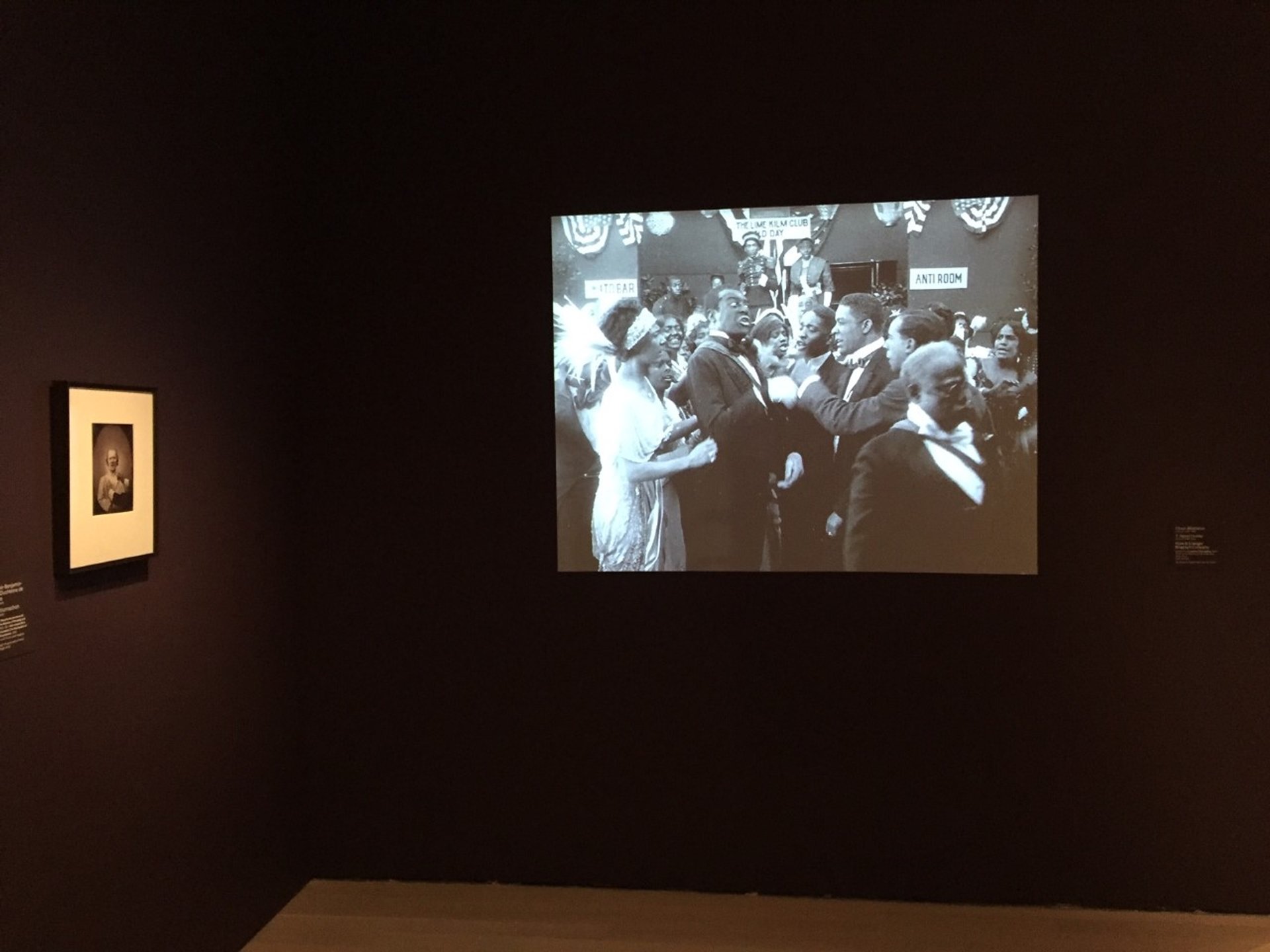

The film adds so much to the discussion about how Modernism began, Roy points out: New York, the metropolis, the working classes, “migration, immigration, urbanisation, mobility, speed”. Given that most visitors heading into the gallery will have relied on that same subway system to get to MoMA, the film offers a way in. Then there is a treasure that lay mislabelled and unseen in the archives for decades: Bert Williams: Lime Kiln Club Field Day, a middle-class comedy filmed with an all African-American cast from 1913.

Bert Williams: Lime Kiln Club Field Day, a 1913 comedy shot with an all-African-American cast

Yes, Starry Night is still there, and Cézanne is still critical, Roy notes. But who knows which of these stories will resonate with visitors most? He envisions young museum-goers telling their friends after a visit, “Guys, you’ve got to go see this Bert Williams film, you know, in the second gallery—oh and there’s this really cool other painting with like, kind of a trippy sky?”

If you were raised with the notion that in a crazy world gone mad, museums were something stable, this is going to be hard

For Temkin, such curation is about writing short stories. For Sarah Suzuki, a curator of drawings and prints who is overseeing the opening, it is a way of drawing constellations. For Roy, it is about telling the truth.

The curators are meanwhile bracing for the full range of reactions. “Of course,” says Roy, “angry is hopefully too strong a word, but if you were raised with the notion that in a crazy world gone mad, museums were something stable, this is going to be hard.”

Adjustments can indeed be challenging. When the museum closed to the public in June for the completion of construction and the reinstallation, a film crew captured a visitor and the museum’s security supervisor, both visibly reluctant to say goodbye for even a few months to Monet’s waterlilies. Three years before that, a decision to close the architecture, design, drawings and photography galleries at the outset of the expansion process provoked such distress among stalwarts of those mediums that Martino Stierli, chief curator of architecture and design, wrote an open letter to reassure people that MoMA still cared.

Art history isn’t the neat package you think it is

Phase One, unveiled in June 2017, showed off a substantially reworked east wing with a light-filled lobby, new amenities including a lounge, a bookshop, a café and a cloakroom, and generous temporary exhibition spaces. Phase Two was all about the permanent collection.

The museum boasts holdings of about 200,000 objects, of which paintings and sculptures account for less than 2%. But the permanent collection galleries have historically shown little else—and precious little at that (400-odd works at any given time). Photography, design, drawing and printmaking, meanwhile, were long collected and exhibited separately in a constant rotation, given the fragile nature of the mediums.

Temkin recalls a groundbreaking experiment in 2010 which saw the entire fourth floor emptied of its usual contents (the 1940s to the 1970s) and turned over to Abstract Expressionist works across disciplines. “The honesty of presenting a history that wasn’t merely the top six masterpieces—it went such a long way in telling you that art history isn’t the neat package you think it is,” she says. The unexpected dialogues between disparate works illuminating a time and place—New York in the 1950s, in this case—were electric.

The problem with discrete experiments, though, is that most visitors paid them no mind. It became apparent, Temkin says, that the museum needed a systematic rotation of the permanent galleries with everyone in the museum on board, which led inexorably to the painstaking reinstallation.

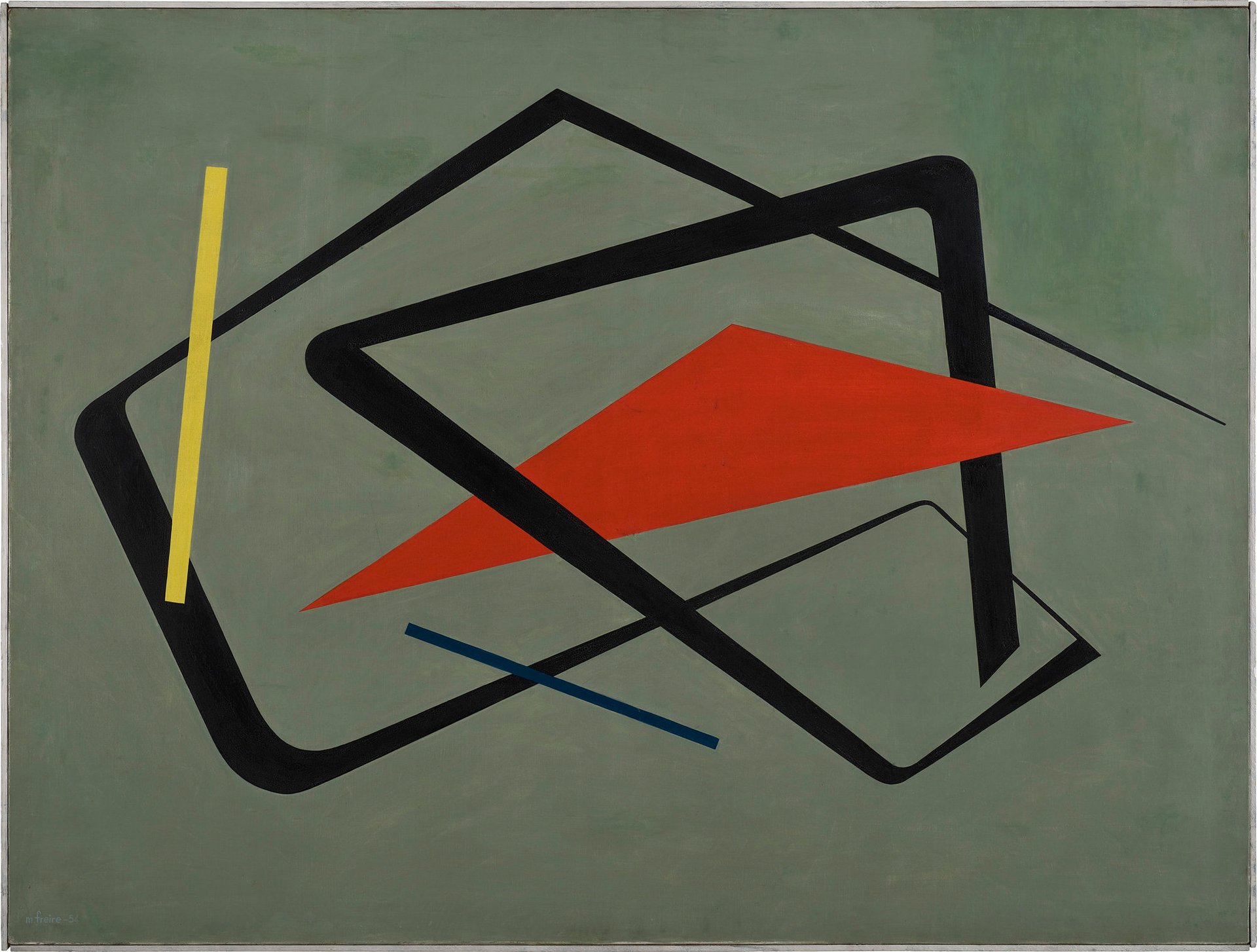

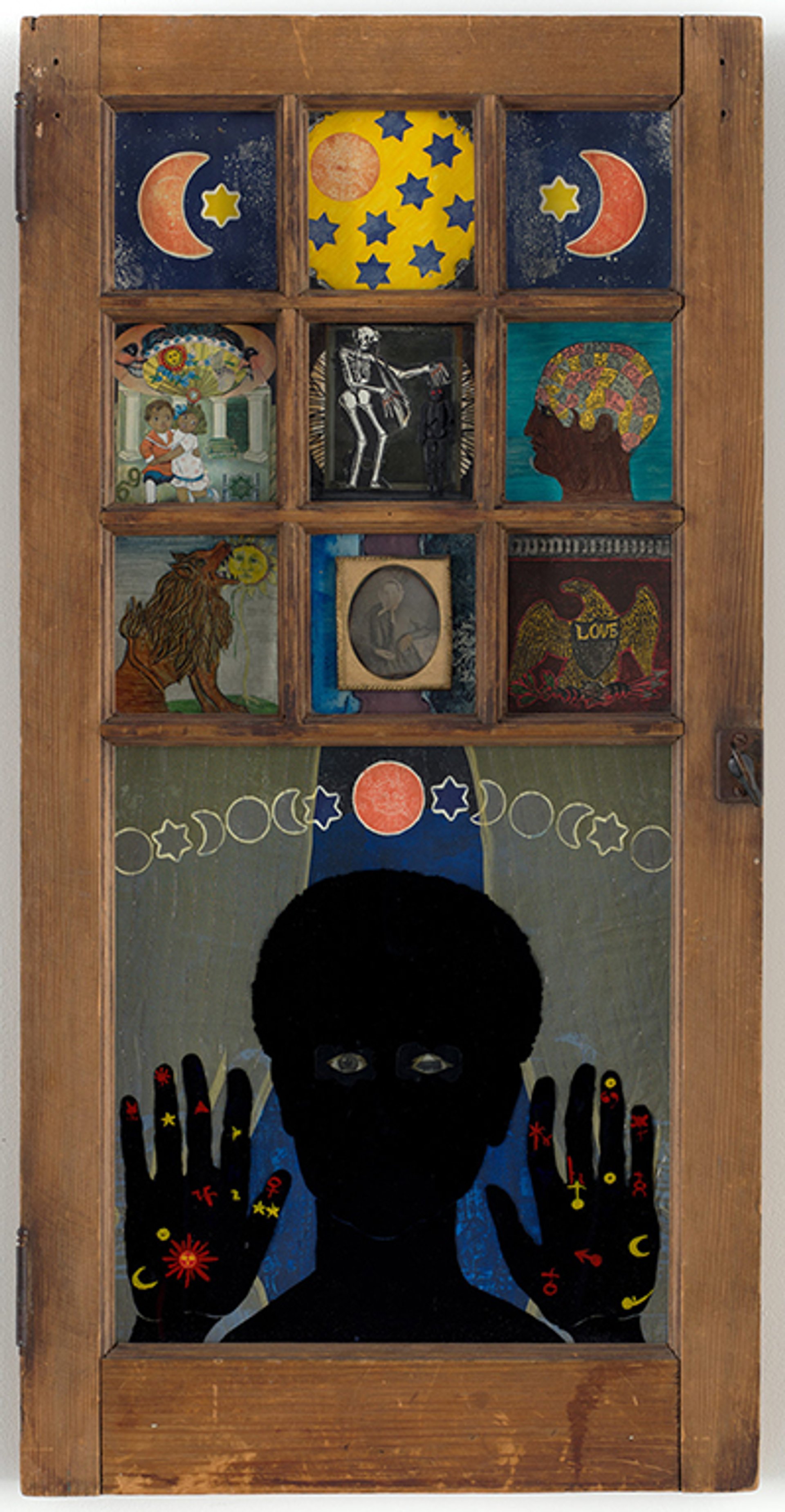

MoMA has also organised three temporary exhibitions opening on 21 October. The largest, a display of abstract works by leading Latin American artists, is drawn primarily from art donated to the museum by Patricia Phelps de Cisneros. A show devoted to the artist Betye Saar will explore the relationship between her 1969 assemblage Black Girl’s Window, a work in the permanent collection, and the artist’s experimental print practice. And an exhibition will focus on landmark performances by the multidisciplinary artist Pope.L.

A 1954 untitled painting by the Uruguayan artist María Freire Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Patricia Phelps de Cisneros through the Latin American and Caribbean Fund in honor of Gabriel Pérez Barreiro

Betye Saar's Black Girl’s Window (1969) Rob Gerhardt/© 2018 Museum of Modern Art, New York

Visitors are also expected to flock to MoMA’s new Studio, a dedicated space for performance, process and time-based art that will connect to content in the surrounding collection galleries and challenge accepted narratives of art history. The first offering is an immersive sound installation, Rainforest V (Variation 1) and the electronic music performance Forest Speech by David Tudor and Composers Inside Electronics. The museum is also promoting a new education center known as the Creativity Lab, where visitors are encouraged to drop by to take part in conversations arising from the installation of the permanent collection.

MoMA's new Studio, where visitors can hear Rainforest V (Variation 1), an immersive sound installation, and Forest Speech, an electronic music performance.

Amid all the changes, it is easy to forget that MoMA was a radical idea to begin with. Suzuki describes the new iteration as a return to the ideals of the museum’s founding director, Alfred Barr, and his notion of the museum as a laboratory for experimentation. “It was a moment when the story did not feel as codified,” she says. “There was tremendous excitement and freedom in that.” Re-examining the collection has renewed that fervour.

It is not only about finding hidden treasures, Temkin points out. It is also about what is missing, although she avoids the idea of gaps to be filled: she prefers to think that there is a fuller history to be proud of. “For me, one is never done,” she says. “There are always new chapters.”