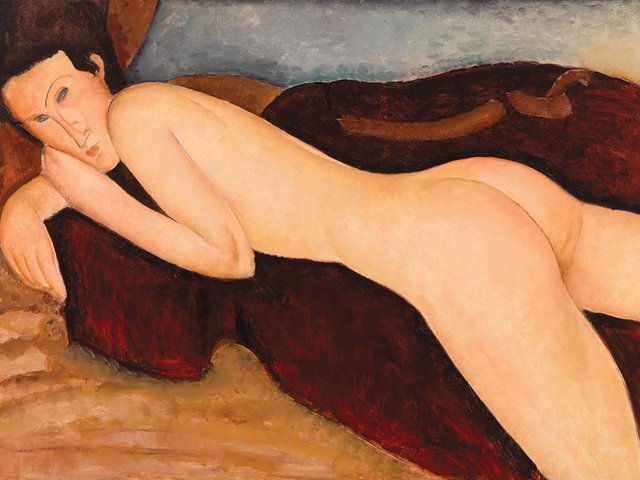

Ten French museums and their national scientific laboratory have begun a forensic two-year examination of all the Amedeo Modigliani works in French public collections—leaving scholars divided over how it might affect the forgery epidemic plaguing the artist’s market. The project, known as Modigliani and his Secrets, will scrutinise 29 pieces: three sculptures and 26 paintings, of which one, a portrait of a brunette owned by the Musée des Beaux-Arts de Nancy, is no longer considered authentic.

This is the first comprehensive study on an artist in French collections since a project dedicated to Van Gogh was undertaken in 1999, says Marie-Amélie Senot from the LaM, Lille’s Modern art museum, which is leading the investigation. The LaM has 14 Modigliani portraits, the highest number in any French museum, thanks to its founding donor Jean Masurel, whose uncle began collecting the artist’s work in 1917. This group of works was the core of a 2016 Modigliani survey there, which triggered the scientific initiative.

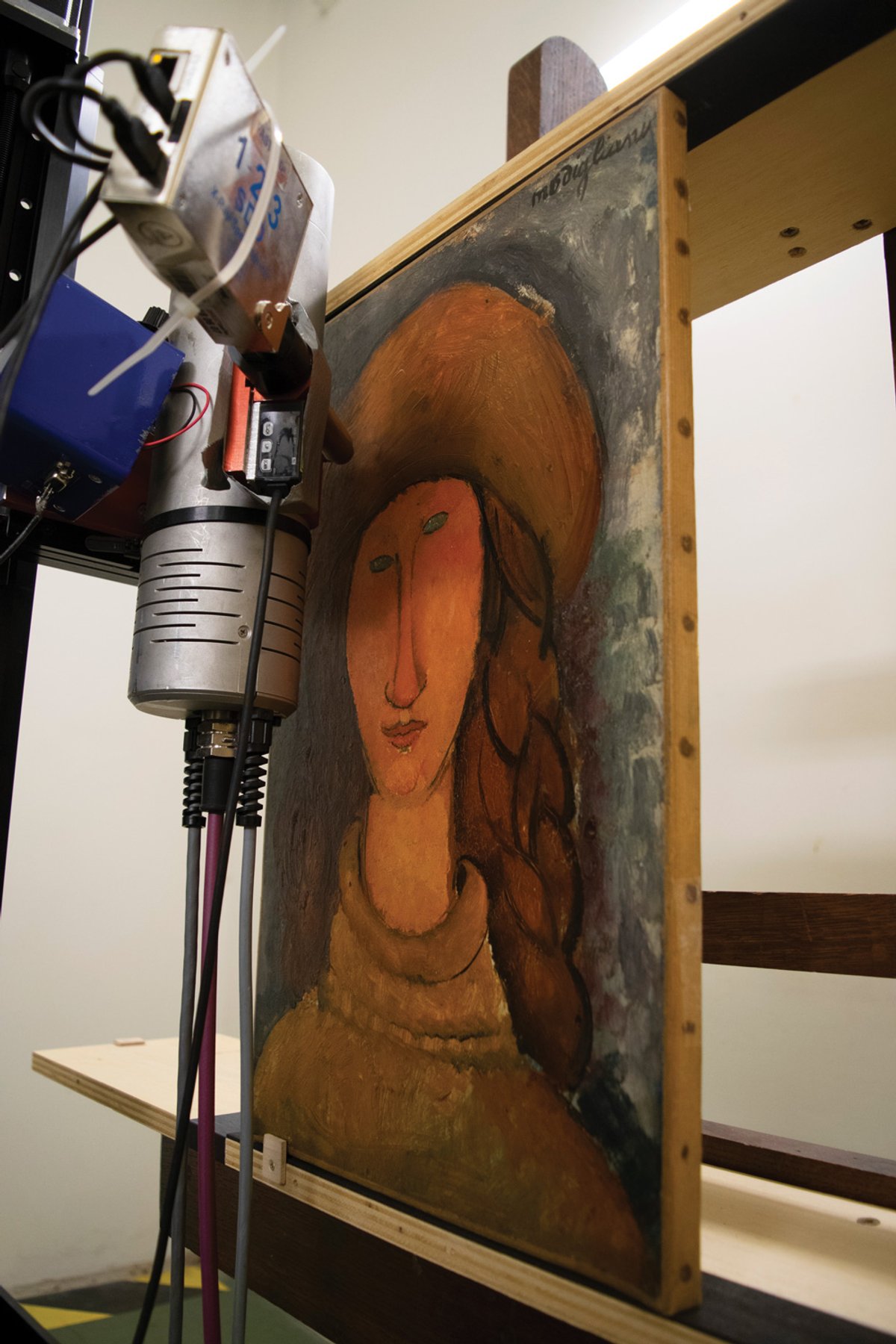

The Centre for Research and Restoration of the Museums of France (known as C2RMF), based in the Musée du Louvre, began examining the first works in May. The Centre Pompidou, the Musée Picasso and the Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris are all submitting pieces, along with museums in Grenoble, Nancy, Rouen and Troyes. The national laboratory at C2RMF will conduct scientific imaging and the chemical study of synthetic pigments. In Lille, the laboratory of the National Centre for Scientific Research will examine the organic materials.

The study is due to conclude in December 2019, with a publication and symposium expected to follow in 2020, the 100th anniversary of the artist’s death. “Experts will be welcome” to comment on the findings, Senot says. They include the French scholar Marc Restellini and Kenneth Wayne in the US, who are working on separate catalogue raisonnés of the artist.

Restellini welcomes the French study but says he is disappointed at not being consulted, having “developed scientific research on the artist for the past 20 years”. He has some “doubts about the interpretation” the museums might make of the results and opposes the publication of technical findings, on the grounds that it “will help forgers to make their fakes”. The latest Modigliani controversy erupted in January this year, when prosecutors in Genoa declared 20 paintings exhibited at the Palazzo Ducale to be forgeries.

Restellini says he will publish his catalogue raisonné in 2020. It was commissioned in 1997 by the Wildenstein Institute, with which he parted company in 2014. He has no relationship either with Wayne’s Modigliani Project.

Senot stresses the French study’s independence from Restellini, Wayne and the Modigliani market. “We might exchange information of course, but the scientific importance of our research relies on the fact that it has no financial impact whatsoever,” she says. “These are public works, by an artist who is very popular, so we have an obligation to present the results to a wide audience.”

What is more, “better knowledge is the best weapon against forgery”, believes Michel Menu, the head of the C2RMF research department. “Naturally, forgers try to update their techniques and it makes our work much more delicate,” Menu says. “Still, offering data to scholars, curators, journalists, dealers and the public is the best way to detect and reveal the forgeries that are out there.”