When you enter a period room, you are invited to feel like you have been transported to a real place where a real person once lived. But the Minneapolis Institute of Art (Mia) wants you to know that may not be the case. On 22 April, the institution unveiled an unorthodox overhaul of six of its 17 period rooms as part of an ongoing initiative to change the way the public thinks about these spaces.

Until recently, Mia—one of the first US museums to bring period rooms into its collection in the early 20th century—used two of its newly-refurbished rooms, the 1772 Charleston Dining and Drawing Rooms, to tell the story of decorative arts in the American colonies. But colonial furniture had no connection to the rooms’ original inhabitant.

“Early on, period rooms were sourced by antiques dealers for museums that were eager to represent period style—they weren’t looking at authenticity,” says Jennifer Komar Olivarez, Mia’s head of exhibition planning and strategy. More recently, the once-popular spaces have been “treated as pass-through spaces”, Komar Olivarez says. “They weren’t paying off anymore.”

With grants from the Milwaukee- based Chipstone Foundation and the National Endowment for the Arts, among others, the museum set out to learn more about the owner of the Charleston rooms: Colonel John Stuart, the South Carolina-based Commissioner of Indian Affairs for Britain’s southern colonies. In the late 18th century, he helped to maintain peace between British settlers and Native Americans. Curators delved into early South Carolina legislative records and confirmed that Stuart was a slave owner (he owned some 200 slaves). They also researched Stuart’s family tree and learned more about his Cherokee son.

They then looked for objects to tell these previously untold stories. In the dining room, curators added an English tilt-top table that better reflected Stuart’s taste for British furniture, and grass baskets like the ones that slaves on his plantations would have used.

Curators also added non-traditional elements, such as contemporary art, period clothing and video interviews, to explore the role of Native Americans and enslaved Africans in Stuart’s world. Without them, the curators say, he would have had neither wealth nor status.

“Almost by default, the narratives about individuals in these rooms tend to be about those in positions of power,” says Alex Bortolot, Mia’s content strategist. “One of our primary callings… is to invite the voices of those who have largely been marginalised in the telling of American history back into the rooms.”

Although some visitors may be surprised by Mia’s new approach (on view until 15 April 2018), the curators say they are not taking as many liberties as one might think. In fact, most period rooms do not contain original furniture. The only component of the Charleston rooms that came directly from Stuart’s home is the wall panelling. “These rooms are constructions—but so is history. This project illustrates that very clearly,” says Jan-Lodewijk Grootaers, the museum’s curator of African art.

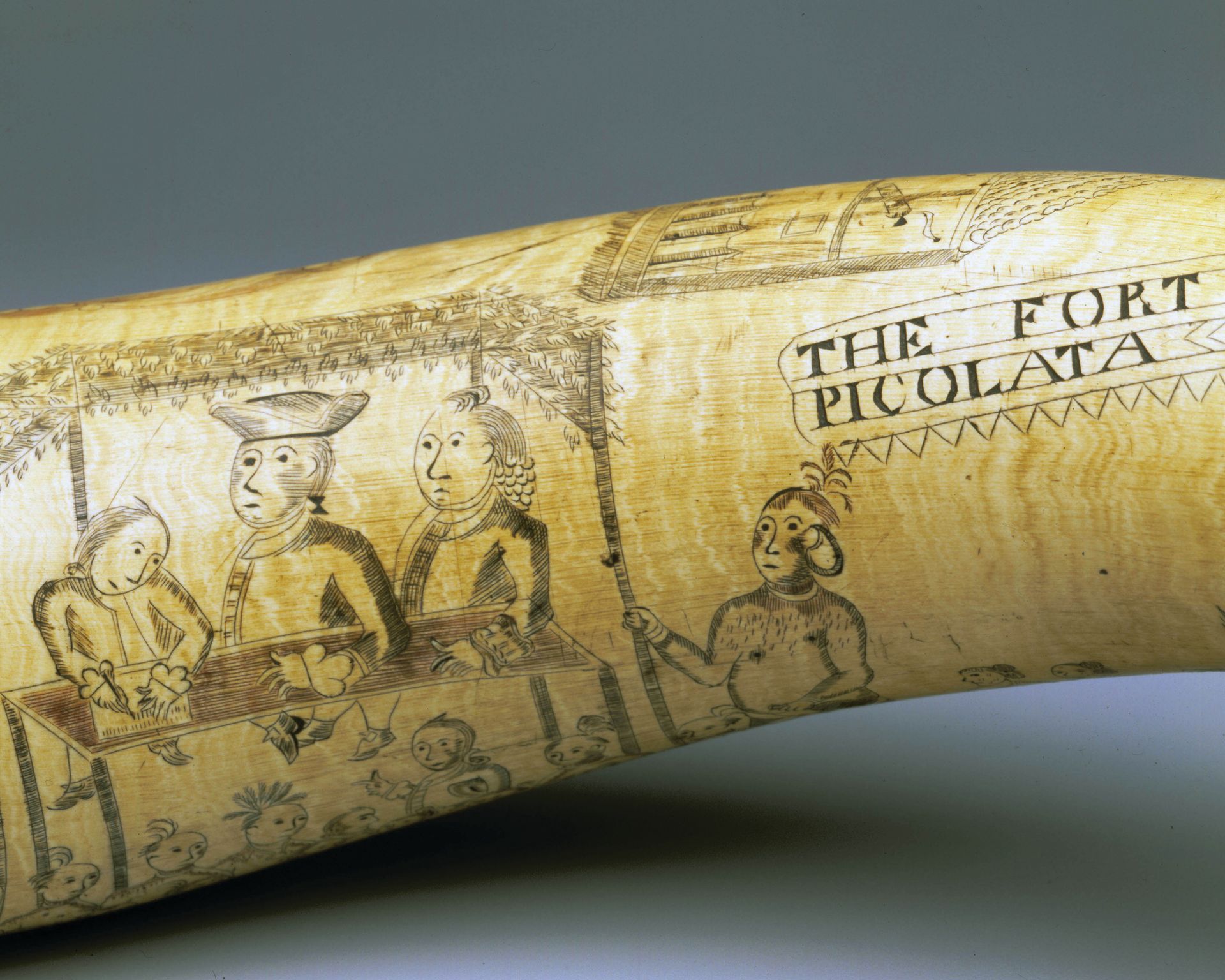

Treasure hunt: objects found for the Charleston Rooms Powder horn with scenes from the Indian Congress at Fort Picolata (1768)

This powder horn includes the only known portrait of John Stuart (the figure in the tricorn hat). It is a carving of the first Indian Congress in 1765, where he helped negotiate a land treaty with the local Creek people. Curators discovered the powder horn in the collection of John and Marva Warnock in 2015 and then used an eyewitness account to identify Stuart in the carving.

Shan Goshorn’s Playing Their Hand (2013)

The Native American artist Shan Goshorn created this work after examining a Cherokee gambling basket in the archives of the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, DC. The exterior features historical accounts of three Cherokee warriors’ journey to England to visit King George III in 1762.

Cherokee artist’s bandolier bag (1825-50)

Curators searched for objects to illustrate the diplomatic exchange between Cherokee and British representatives during Stuart’s time. This bag—as well as the moccasins and sash that are displayed elsewhere in the room—is similar to those worn by Cherokee leaders during negotiations with the British.