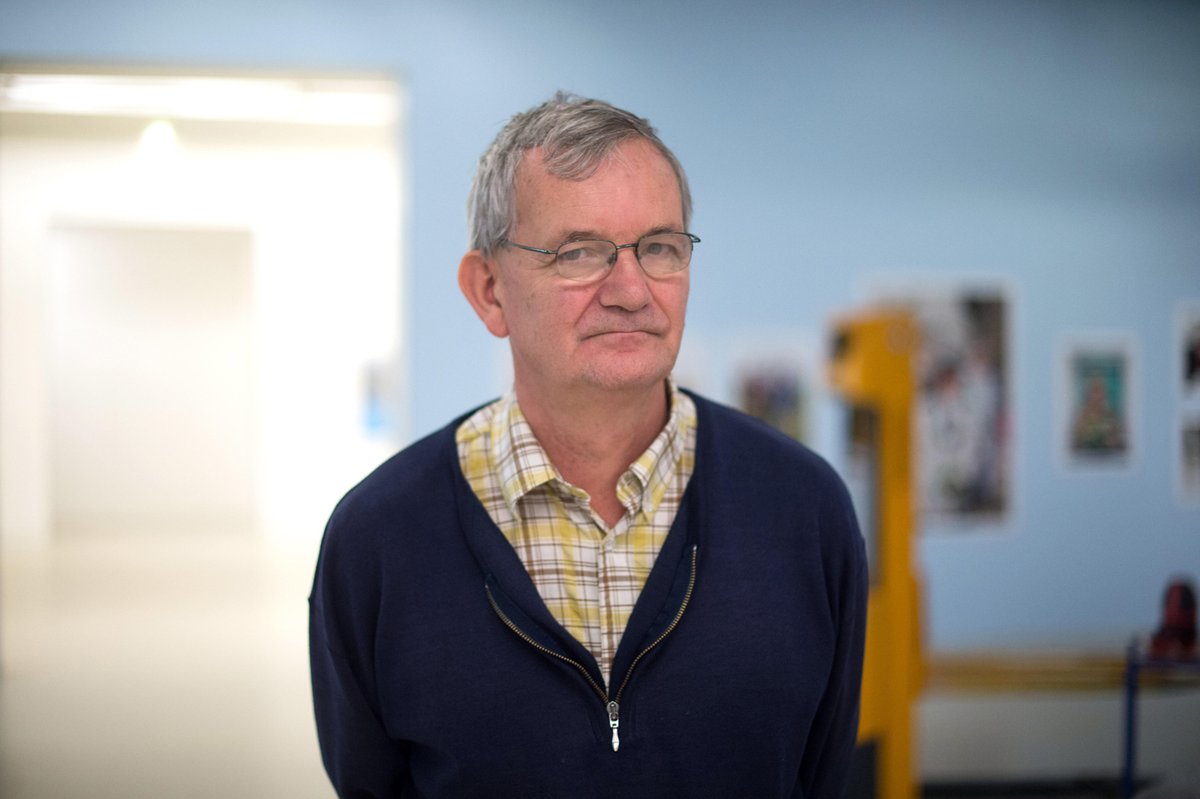

Martin Parr’s decision to quit as artistic director of the inaugural Bristol Photo Festival has sparked a heated debate on how so-called 'cancel culture' relates to the handling of historical photographs and industry elites.

The debate centres on Parr’s promotion and apparent editing of the Gian Butturini book titledLondon, which includes a street portrait of a black woman who worked as a ticket inspector on the London Underground, published next to a picture of an imprisoned gorilla at London Zoo. Mercedes Baptiste Halliday, from London, who is currently a student at University College London, drove an 18-month protest against the book and Parr's involvement, which led to the prominent photographer stepping down from the Bristol Photo Festival this week.

The controversy has raised questions of whether long-established figures such as Parr still deserve deference and respect, and whether potentially problematic images be viewed and discussed at all, or should be lost to time?

In the wake of Baptiste Halliday's campaign, Parr instructed Damiani, the publisher of the book in question, to discontinue publication, and for existing copies of the book to be destroyed.

Butturini's work has, in the modern parlance, been cancelled, despite the protest centring around two images amongst scores of photographs that took years to compile.

In a further message to Baptiste Halliday, which she published, Parr admitted: "This is no excuse, but I'm nearly 70-years-old and a white man and regretfully I'm coming to realise that sometimes I have failed to see things from another perspective.”

Despite Parr's apology and attempts to atone for his support of the book, Baptiste Halliday called for the “ generation of white middle-aged men” that Parr is seen to represent “to be dismantled".

Baptiste Halliday's message has found plenty of support, with Parr viewed as the de facto head of an elite who have traditionally kept photography’s spoils to themselves, and who instinctively perpetuate a status quo that has its roots in racist perspectives.

But opinion has been split. Many photographers think Parr made a genuine mistake for which he has atoned, and are concerned about the quality of genuine debate, as well as our ability to confront challenging images from the past, in a febrile and unforgiving cultural atmosphere.

John Edwin Mason, a photographer and professor of African history at the University of Virginia, says the photography world is now living in a “new reality”.

“The photo industry, especially in Western nations, is going through a time of internal reckoning with racism and sexism, issues that people in power have been able to ignore or push aside,” he says.

Recent social movements and changes in media “have empowered people of colour to challenge the racist norms that have shaped the photo world,” Mason says.

“This troubles many people who aren't used to being held accountable for what they do and say and the harm they cause,” Mason says. “Some of them lash out and foolishly call this ‘cancel culture’. No. It's accountability for doing racist and sexist things, whether it's being blind to a demeaning juxtaposition of photographs or failing to hire photographers of colour. Actions like these are still common. Until relatively recently, photographers had few resources to fight back. Now they do, and some of the powerful and privileged aren't at all happy about it.”

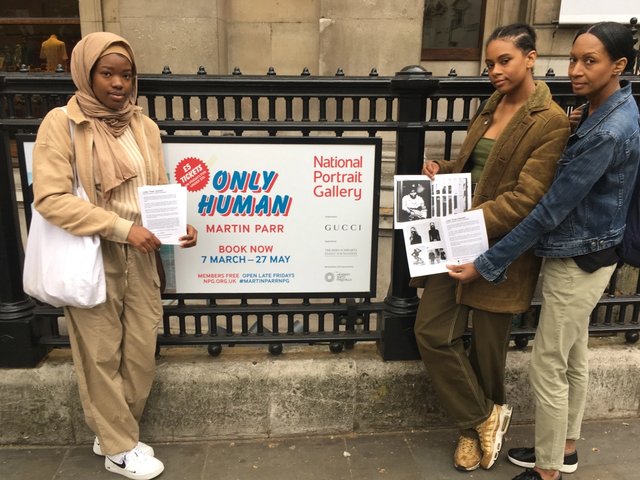

Mercedes Baptiste Halliday has been campaigning against Parr's association with a book of photography by Gian Butturini © Mercedes Baptiste Halliday

Jennie Ricketts, a photography curator and a former picture editor for the Observer, says: “Martin Parr’s apology comes at a significant moment for the photography establishment. A coded language has carried ingrained bias towards black people for far too long. Black people now need to be seen and acknowledged when issues of racism are raised, as Baptiste Halliday did. There then needs to be accountability and reparations made. Anything less simply perpetuates this insensitivity towards black people.”

Brad Feuerhelm, a photographic artist and editor of podcast series Nearest Truth, speaks about the accusations of racism levelled at Parr: “When Parr apologised, he said he had not understood the book was potentially offensive or racist. That, of course, is a problem. But he recanted this position and, in his apology, acknowledged his poor reading as a writer of the preface to the new edition. Does it mean the Butturini's original intent was racist? No. Does it make Parr a racist? No. But it does indicate the perpetuation of problematic issues between photography and race. That needs as wide a discussion as possible.”

Feuerhelm considers Parr’s resignation “a missed opportunity.”

“This could have been discussed with rigour at the festival,” Feuerhelm says. “The claim is serious and should be addressed in an open dialogue, not in tone-deaf silencing. I believe Parr’s apology should have come sooner and with more compassion. I also believe, if his cancellation is the end of the conversation, it has failed to promote corrective growth.”

Damion Berger, a British-born photographer of Jewish heritage, says: "I don’t know what’s more concerning—that Parr has asked for the books to be removed from sale and destroyed, or that his accusers didn’t think to compare Butturini's original 1969 book with Damiani’s facsimile reproduction to see if the edit changed."

Berger adds: “By this new standard, Robert Frank’s The Americans would be thrown on the same bonfire. How would Garry Winogrand’s 1967 picture of the mixed race couple in Central Park each holding a baby chimp be perceived today? As the commentary on interracial prejudice that it was or would the photographer be perceived a racist today?"

"As a Jew, I don’t want every picture of my ancestors during the Holocaust or wearing the Star of David to be purged; quite the opposite. It’s a reminder of a time and way of thinking we must never return to,” Berger says.