The London-born artist Malcolm Morley, known for his innovations in photorealist and neo-expressionist art, has died aged 86. Xavier Hufkens gallery in Brussels, one of the galleries that represent him, says in a statement: “He defied stylistic characterisation, moving through so-called abstract, hyperrealist, neo-romantic, and neo-expressionist painterly modes, while being attentive to his own biographical experiences.”

Morley, born in 1931, grew up in wartime London and served a prison sentence at Wormwood Scrubs Jail for burglary. In 1952, he was offered a place at the Camberwell School of Arts and Crafts in London, transferring later to the Royal College of Art.

He moved to New York in 1958 where he became known for furthering photorealism, producing works that emulate photographs with hyper-realistic clarity.

Malcolm Morley's S.S. Amsterdam in Front of Rotterdam (1966) Private Collection. Courtesy Sperone Westwater, New York

In an interview with the Guardian in 2013, Morley said he preferred calling the movement Super-realism. “Not because I’m saying the art is super, but because it reminded me of Malevich’s suprematism,” he said.

His early technique involved transferring images of Old Master paintings, family portraits and images from travel brochures to the canvas using a grid system. Morley told the Spectator how this technique was born, saying: “Imagery seemed to be filled up. Warhol had done all those Coke bottles—there wasn’t much left. What was I going to do? What I did was paint an ocean-going liner.

“I went down to Pier 57 [in New York] and looked at a huge liner but it was impossible to organise it as a picture. So I got a postcard of it and used the grid, which was what I’d seen at [artist] Richard Artschwager’s. He used the grid. But I used it in a particular way and finished each piece as I went.”

After 1970, his obsessive style became looser and more expressionist, incorporating collage. Key works of the period include Train Wreck (1975); one of two prints he made of the original painting is in the Tate collection. The piece, based on the sculpture of a derailed toy train, explores the themes of tragedy and disaster.

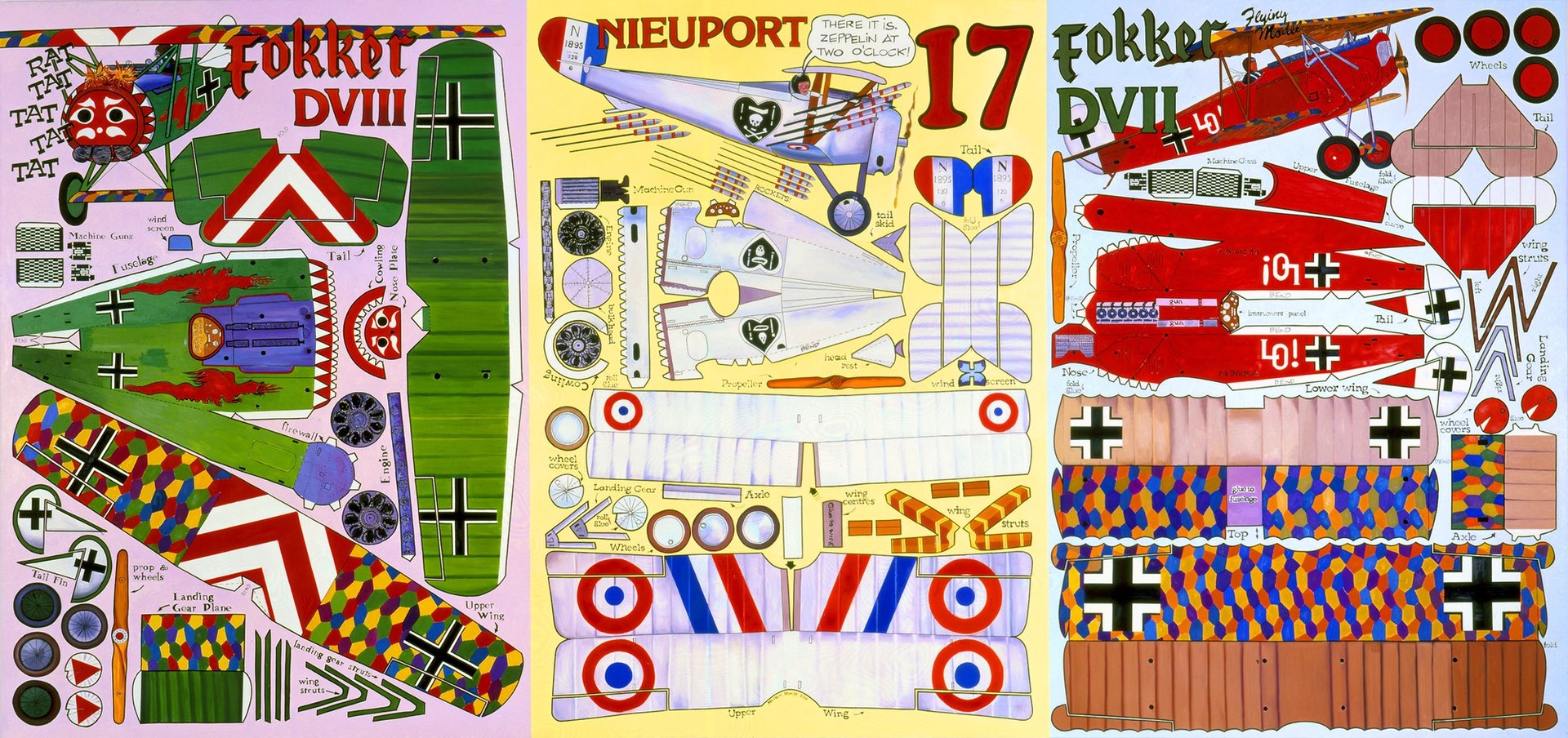

Malcolm Morley's Rat Tat Tat (2001) Collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, purchased with the George A. Hearn Fund, Kathryn E. Hurd Fund, and Andrew and Christine Hall Gift, 2013. Courtesy Sperone Westwater, New York

Morley is also credited as a driving force behind New Spirit Painting, a term which refers to the resurgence of expressionist painting around 1980. Asked about sparking the neo-expressionist art of the era, Morley told the New York Times in 1993: “If I had known that I was going to invent horrors like Julian Schnabel, David Salle and those people, I would have cut off my hands.”

In 1984, he won the inaugural Turner Prize at Tate for his Whitechapel retrospective the preceding year, beating off Richard Deacon, Gilbert & George and Richard Long. Writing in the Guardian, the critic Waldemar Januszczak criticised the decision as Morley had been based in the US for more than 20 years.

“Morley is a painter of uncommon force, an artist who seems to be able to bend the laws of physics. The reasons he should not have won this prize have nothing to do with his talents but concern the identity of the prize itself and our faith in its value,” Januszczak said.

In 2014, a major exhibition of Morley’s works held at the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford, and drawn from the Hall Collection, put the artist back on the art world radar. Last year at Frieze Masters, the New York-based Sperone Westwater Gallery—who also represent the artist—devoted its stand to a survey of Morley’s work from the 1960s photorealist paintings to his expressionistic 1980s pieces.