Recluse Brown (2015–16) (still). Four-channel video installation, sound; 32:19 min. Dimensions variable. © Kaari Upson. Courtesy the artist and Sprüth Magers

Talking to Kaari Upson is like looking at one of her wall-sized drawings. One idea leads to another, tangents splinter down unexpected paths, you travel forward and backward in time simultaneously, and suddenly you’re back to the start and a picture starts to form. This seems to match her artistic practice, where drawings and videos and sculptures develop from and feed into another. For her show at the New Museum, the Los Angeles-based artist is presenting a selection of new (and older) work based on tract housing in Las Vegas, domestic furniture and the ever-present figure of the mother.

The Art Newspaper: Tell us about the show.

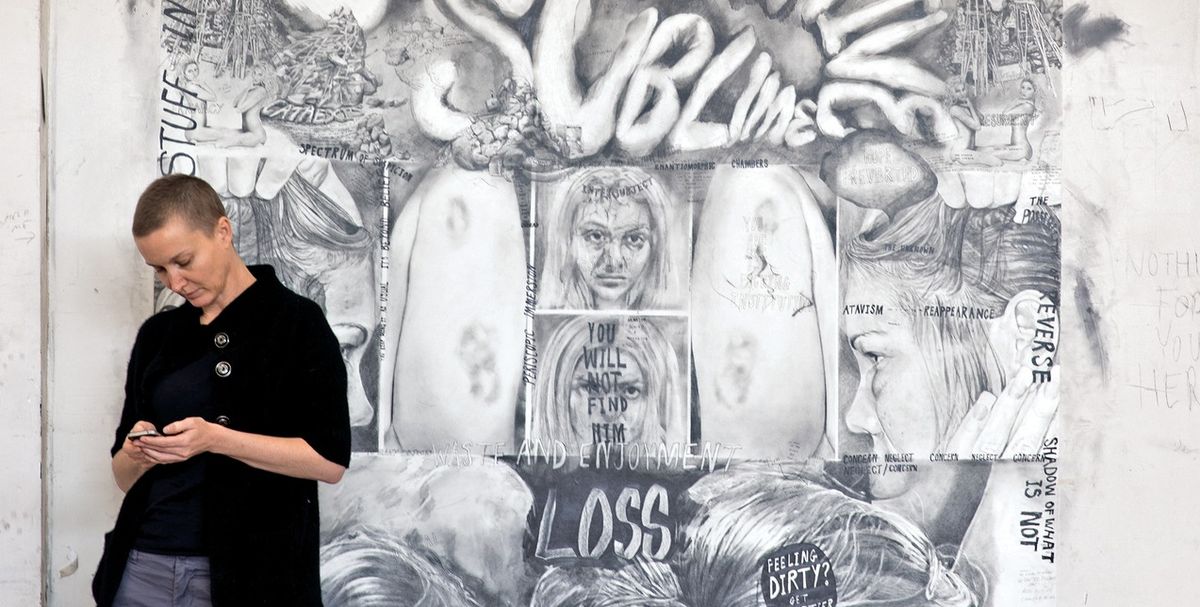

Kaari Upson: There’s no beginning, middle or end in the work. It could be the end of something that I’m not even recognising the line of, but then the beginning of something else that I don’t even know is about to happen. We’re taking a slice of that space [the studio] and then putting it into the museum. There are very large-scale drawings. They’re not finished; some of them started five years ago, so they’re drawings I work on. Some people have described them as the unconscious of certain sculptures.

When I work on one drawing, and I add the first text, or even an image, it’s recycled back in on itself. Then an accident of two texts that I’m researching might overlap an image that I put on. The next thing that happens is that I make a video, and then an image from the video might make its way back in. As these things layer, it generally points to a direction of an answer to how a three-dimensional object might get made. It just keeps happening, so I keep trusting that.

It’s a literal drawing board that you’re constantly going back to.

Yeah. People say it’s mental mapping; I don’t know, I’ve just always drawn like that. Even when I write my notes down, they look just like my drawings. I love drawing, I find it very meditative. Because everything else that goes on in the studio is extremely experimental, even the casting processes that we use. I don’t like to use traditional means to make an object, I like to make something that could definitely go wrong, or where you don’t know what could possibly happen in the outcome. The only thing that gives me grounding is when I come back to the drawing and just sit there for hours.

Will there be objects in the show related to the drawings?

I would see it that way, but I don’t know if that would be coherent to the viewer.

There is a skin cast of a real fireplace from a house in Las Vegas. I’m following tract houses in Vegas, some built between 1979 and 1981. The source house that I’ve been working with for years has this two-sided, classic 70s stone fireplace, and when I cast it, it took a trace amount of the actual stone surface, and I used a special technique that made it thin like paper. So the cast of [the fireplace] is in the room with the drawings, because it points to the larger project that’s going to take years to develop.

There’s a very large-scale sectional couch. It will be important later because it appears in videos. It keeps reappearing—there’s a couch behind a couch behind a couch.

The 90-degree angle in the couches became important to me. I started to make these objects many years ago; the first couch I made was just four of those 90-degree angles cast at different gravities. That piece is in the New Museum show. It looks like the most beautiful and deformed hole in the body.

I can get very formally obsessed with things. On my drive to [my studio], which is only five minutes, there are couches upon couches upon couches, and I actually have to hold myself back. There was a new one and it had fatty layers of leather, and I just wanted it so bad. But I don’t make them anymore. With the works in the Whitney Biennial, I left it all on the field, I did everything I needed to do with couches. And they’re done. There’s no more. I need to make different objects now.

So the ones that are coming back to the New Museum are on loan from Dakis Joannou, the great collector in Greece. He is loaning the original one, and the one I made toward the end that has the Angelina Jolie death-mask face in it, which appears all throughout the show. It’s become this kind of surrogate. What do you call it when you have a little doll? Like an object that you transfer onto? The show is called Good Thing You Are Not Alone, and it’s about this doubling—it’s beyond doubling right now, it’s this multiplicity. And my work is always about that, extensively.

Then in one of the side galleries is a pretty monstrous minimalist sculpture. And when I say monstrous, we’re talking 17 feet by 9 feet by 20-plus feet. Like one giant minimalist cube that reflects on bulk buying and Costco and… “cat beds”, I call them. They’re made in a human form.

The body that I inhabit in all of the videos is based on a very neutralised woman—my mom is a beautiful woman, but went into this zone where her worth wasn’t measured by objectifying her, and she just became this neutralised woman—they’re called The Hers. The Hers are manifested now as cat beds, for a good reason. The cats sleep on them; they love them.

So now, what was considered the invisible woman, the woman that nobody looks at… everything kind of dominoes, hits itself, and things that are accidental or reacting to something else, manifest in objects sometimes. The cats sleep on the chests of these dolls, and now the cats have surrogates, this place to put their love, or whatever it is.

And then inside that minimalist cube, there’s an environment in which people can sit and read my curated collection of Idiot’s Guides: Idiot’s Guide to Physics, Idiot’s Guide to Intimacy. I’ve collected them over many years. I originally bought them for the Larry Project ten years ago. I needed to do graphology, so I bought the Idiot’s Guide to Graphology. And when I couldn’t figure out how to do it, I contacted the woman who wrote the book. So I’ve been using them for years. But now it’s gone wild; it’s Idiot’s Guide to Nazi Germany, Idiot’s Guide to Potty Training—it’s everything. And I like that there’s this kind of pathological scratching at getting all the information. They’re very similar to my drawings. It’s that same kind of organising, framing information.

So we are really getting a slice of everything you’re working on.

Yeah, I think it’s funny, because I think that would make a lot of people very nervous, thinking “Oh, you’re going to look at an unfinished body of work”. I don’t know if there’s anything I do—I guess the sculptural stuff that you see at the Whitney is the closest thing to an unchanging, static, "here it is, it’s done", object. That’s maybe the closest you get in anything I make. Because I use fugitive materials, or drawings where, if you put it in front of me I’ll endlessly draw on them, they will never be the same. I made objects that are meant to be broken down, and sculpture that’s meant to become a drawing or dust. I’m not really interested in saying when something is finished.

• Kaari Upson: Good Thing You Are Not Alone, New Museum, Until 10 September