John Waters has long made his love of Baltimore known, setting many of his cult classic films in his native city. Today, the director of Pink Flamingos and Hairspray cemented his artistic legacy there by donating around 375 works from his fine art collection to the Baltimore Museum of Art (BMA). The gift includes photographs and works on paper by artists such as Diane Arbus, Nan Goldin, Lee Lozano, Richard Prince, Cindy Sherman, Andy Warhol, and Christopher Wool, as well as 90 works by Waters himself, making the museum the largest archive of his art. To honour his generosity, the museum will rename a rotunda in its European art galleries after the film-maker—as well as a pair of restrooms in the East Lobby, “per his request”, the institution notes.

“The first art I ever bought was a two-dollar Miró poster at The Baltimore Museum of Art gift shop back in the 50s when I was a child,” Waters says in a statement. “After taking it home and hanging it on my bedroom wall at my parents’ house, I realized from the hostile reaction of my neighborhood playmates that art could provoke, shock, and cause trouble. I became a collector for life. It’s only fitting that the fruits of my 60-year search for new art that could startle, antagonize, and infuriate even me, ends up where it all began—in my hometown museum.”

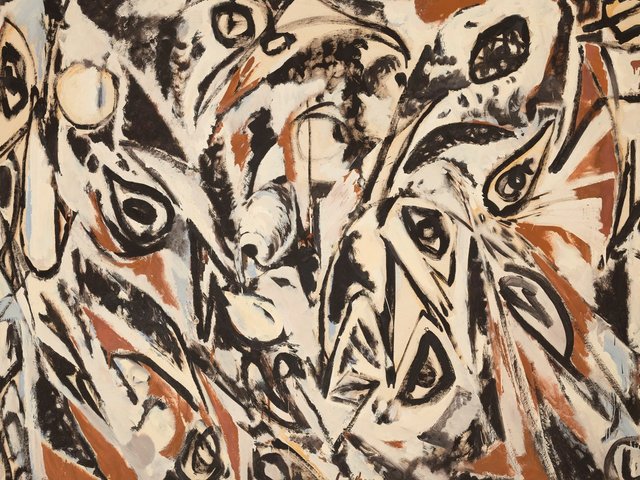

Gregory Green, Work Space #7 (1998) Photo: Jen Berg/John Waters Studio

Waters’s collection, much of which is installed in his home, features in-depth holdings of works by Peter Fischli & David Weiss, Mike Kelley, Karin Sander and Richard Tuttle, and will fill gaps in the museum’s own collection of work by artists including Catherine Opie and Thomas Demand. An exhibition of works from the gift will be staged at the museum within the next five years, it says in a statement.

“John’s generosity, friendship, and commitment to his hometown are boundless. We are deeply grateful to him for entrusting us with his collection and for giving us the opportunity to engage our many audiences with it. We look forward to collaborating with John on the presentation of his collection gift and to finding new ways of sharing the stories and experiences that it holds with our community,” say Clair Zamoiski Segal, the chair of the museum’s board, in a statement.

Tadashi Kawamata, Destruction no. 8 (2016) Photo: Jen Berg/John Waters Studio

The gift comes with restrictions against any of the works being sold, however, a notable arrangement in light of the recent backlash the museum faced after it tried to deaccession some high-valued works from its collection. Waters told the New York Times that he was against the deaccessioning, adding that one of the works potentially on the block, Brice Marden’s “3” (1987-88), is a piece he has dreams about. But the controversy did not derail his commitment to give his collection to the museum, where he has previously shown his work in the 2018 exhibition John Waters: Indecent Exposure.

“As with other significant collections with the museum, John’s collection is developed through an acute personal sensibility that harnesses the power of art to elicit humor, provoke questions, and challenge long-held traditions and norms,” says Christopher Bedford, the museum’s director, in a statement. “This vision melds seamlessly with the BMA’s own mission to upend the standard narrations of art history.”