The Belgian artist Wim Delvoye is showing his inventive, innovative and occasionally controversial works in his first Swiss retrospective at the Museum Tinguely (14 June-1 January 2018). The exhibition, organised in collaboration with the Mudam, Luxembourg’s museum of Modern art, highlights how, since the late 1980s, Delvoye has combined the “profane with the sublime… [In his work] tradition clashes with utopia, and craftsmanship with high-tech,” the organisers say. We spoke to him about his enduring love of tattoos (on pigs and humans), Jean Tinguely and turds.

The Art Newspaper: Have you always been interested in Jean Tinguely’s work?

Wim Delvoye: I have always found Tinguely to be a very interesting artist. He is the person who started making machines that ended up becoming high art, so it’s almost more a question of legitimisation than inspiration. He consolidated the idea of moving machines, referring back to the early 20th-century industrial revolution. But when I made my first Cloaca [excrement-making] machines, I did not want to make any nostalgic references. In 1996, it was all about Dolly, the cloned sheep. Then in 2000, [the US scientist] Craig Venter mapped the human genome, so in that context, I launched my Cloaca Original machine that very same year.

You made your mark with Cloaca, but have you updated it in any way?

Nowadays, the only thing I have to do with the Cloacas is to maintain and improve them. I don’t even respect the historical look, like finding the right colour for instance. I treat them as living things, not like paintings that have stopped in time. Cloaca is a living project; there are ten machines, of which there will be three on show in the Tinguely museum. It is obvious there is a mechanical dialogue [in relation] to Tinguely’s installations, so I wanted to highlight this.

Why did it make such an impression?

The Cloaca machine was built for museums from the very get-go; it’s a very institutional kind of work. You need people on the ground to maintain and control it, to nurture and feed it, replace the silicone tubes, clean up after it. It has been shown in more than 30 museums since 2000, and there have been different controversies linked with different nationalities and countries. In Lyon, France, for example, a great gastronomic city, the citizens were only interested in what the machine ate, and they didn’t really care about its excretions. Chefs even came in to create special meals. In Düsseldorf, a very Protestant town, the German newspapers were full of reports saying: “How dare he? There are so many people dying of hunger.” Just the idea of wasting food was so shocking for Protestant Germany. Everyone is so different in Europe. In Vienna, where I showed Cloaca at the Kunsthalle [in 2001], I mingled in the crowd, and you hear all these stories, people talking about their childhood, their special place for shitting, how they collect their shit… you definitely know you’re in the place where Freud lived and devised his theories. It was astonishing.

The Spud Gun sculptures in the show are considered both mechanical and sculptural items?

I also had to think about what else I do with machines, so I made a couple of Spud Guns. They’re very beautiful and they look a little like small Cloacas, in the same bricolage style, very shiny, techy and boyish. You use potatoes to shoot with them, and they can badly hurt someone. It’s all about defending yourself today against bad people, against governments, against violence. It seems to me there is more aggression, opposition and violence now. Making a shit machine was like a flower-power time in comparison.

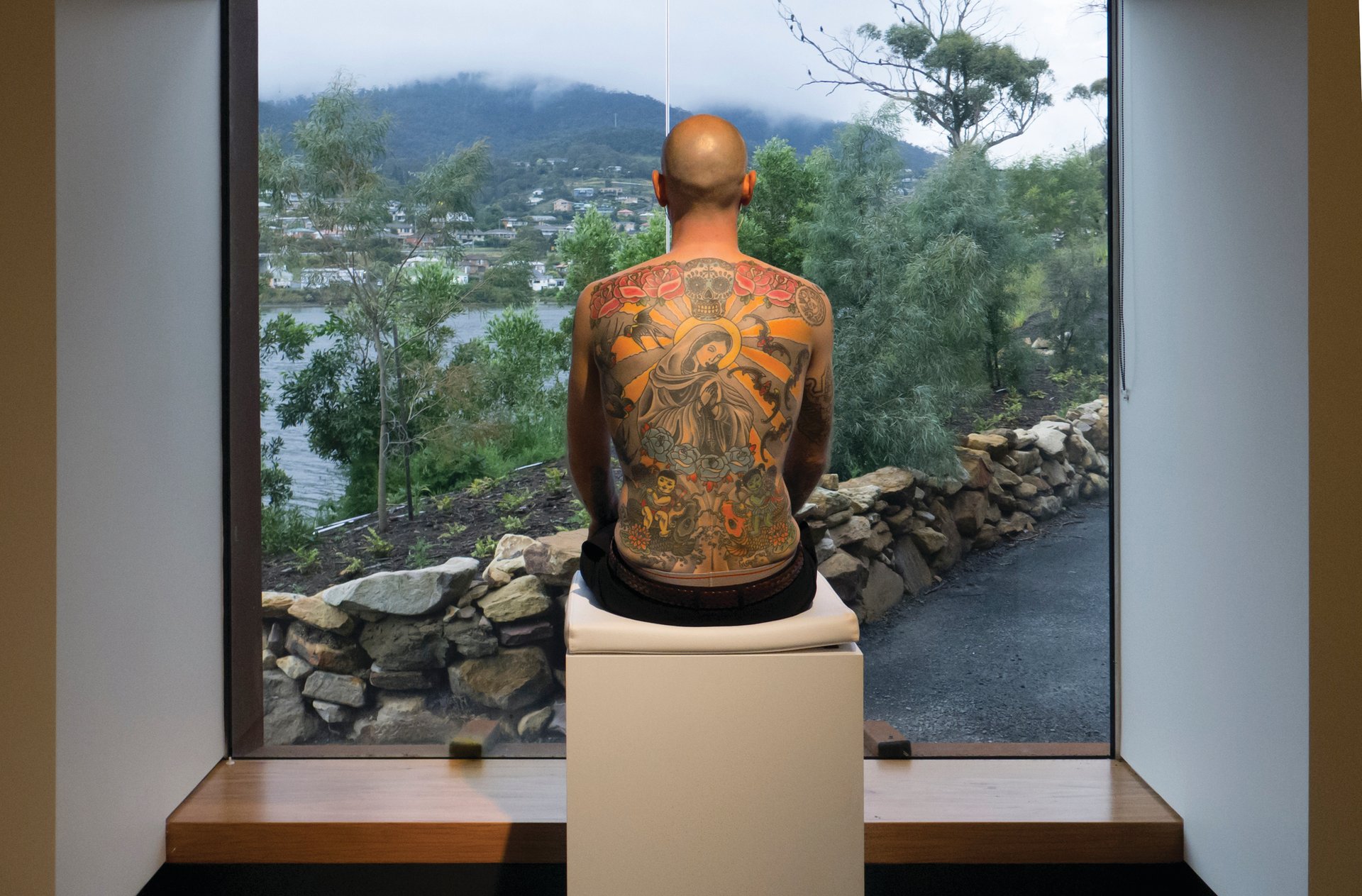

Tattoos have been integral to your practice— I’m assuming Tim, your human canvas, will appear?

Yes, Tim the tattooed man will be on display in Basel, as he’s now accepted as a regular work. He was also featured in my [2011] retrospective exhibition at Mona in Hobart, Tasmania. The museum owner, David Walsh, agreed that he would be paid for a week. Then when they met him, he was so charming and blended into the local scene so well that a couple of weeks became a couple of months, and in the end he stayed for six months. He sat in the show for eight hours, not moving, just like a performance. He is certainly in the top five of my most famous works. Tim really hopes that the collector who owns the tattoo, a German guy called Rik Reinking, will put him up for auction. He would love to do the catwalk at some auction house. And it would raise many issues in an ironic way.

The show also includes childhood drawings; how do they pre-empt your later works?

The childhood drawings I will be showing at the Tinguely also needed to be part of this “retrospective”. I was very productive in kindergarten and these drawings are primitive, childish doodles. The idea actually came from my show at Mudam [held earlier this year]; it’s like a leftover from that exhibition. There is evidence of craftsmanship also in the show, like the nine stained-glass windows [the works such as Euterpe (2001-02), incorporate X-ray images of people having sex, body parts such as intestines and skeletons], Gothic laser-cut stainless steel works, and embossed aluminium work.

You always like to make a statement, but can artists really make understated works?

[My art] is fearless. So far, I’ve done well just because I’m that fearless. Most artists fall from their horse; they make some kind of agreement, they only have to do 20 paintings a year and so on. But if you want to make rapid and entertaining evolution so that your public can hardly keep track of your thoughts, to make sure you’re always one step ahead, you have to work hard and produce a lot, try out new things. For that reason, I always admired [the German artist] Thomas Schütte: he did so many different things with oil on canvas in the 1980s, for example. I was still trying to climb my way up when he was already making fearless art.

And this sense of adventure perhaps fuels your initiatives abroad. You’re restoring several historic buildings in Kashan, northern Iran.

It is quite remarkable how much I’ve achieved in Iran. Strangely, I am asked less questions there than in the West. I feel more free there. It’s not perfect—we’ve had delays, but things are always resolvable. And I’m ahead of everyone else, going there: I have the support of the ministry of culture and officials who run local museums. I’m expecting a big China moment—it’s like Russia in 1991. And I like the contrarian aspect [of Iran]. I’m not making any political statements, though: I have no political opinion. I just want to restore these 18th-century houses.

And you collect also. Why?

I loved to collect archaeological pieces, vintage photography and 17th-century Old Masters. I have marble pieces from the 16th and 17th centuries for example, but it’s not a collection, more a story of opportunities. I move on from one interest to another, but prices are so low that I cannot resist. I was into antiquarian books. But I stopped as it was also very unsexy. You won’t get laid, Gareth, if you ask someone to come and see your old books.

Wim Delvoye: bigging it up

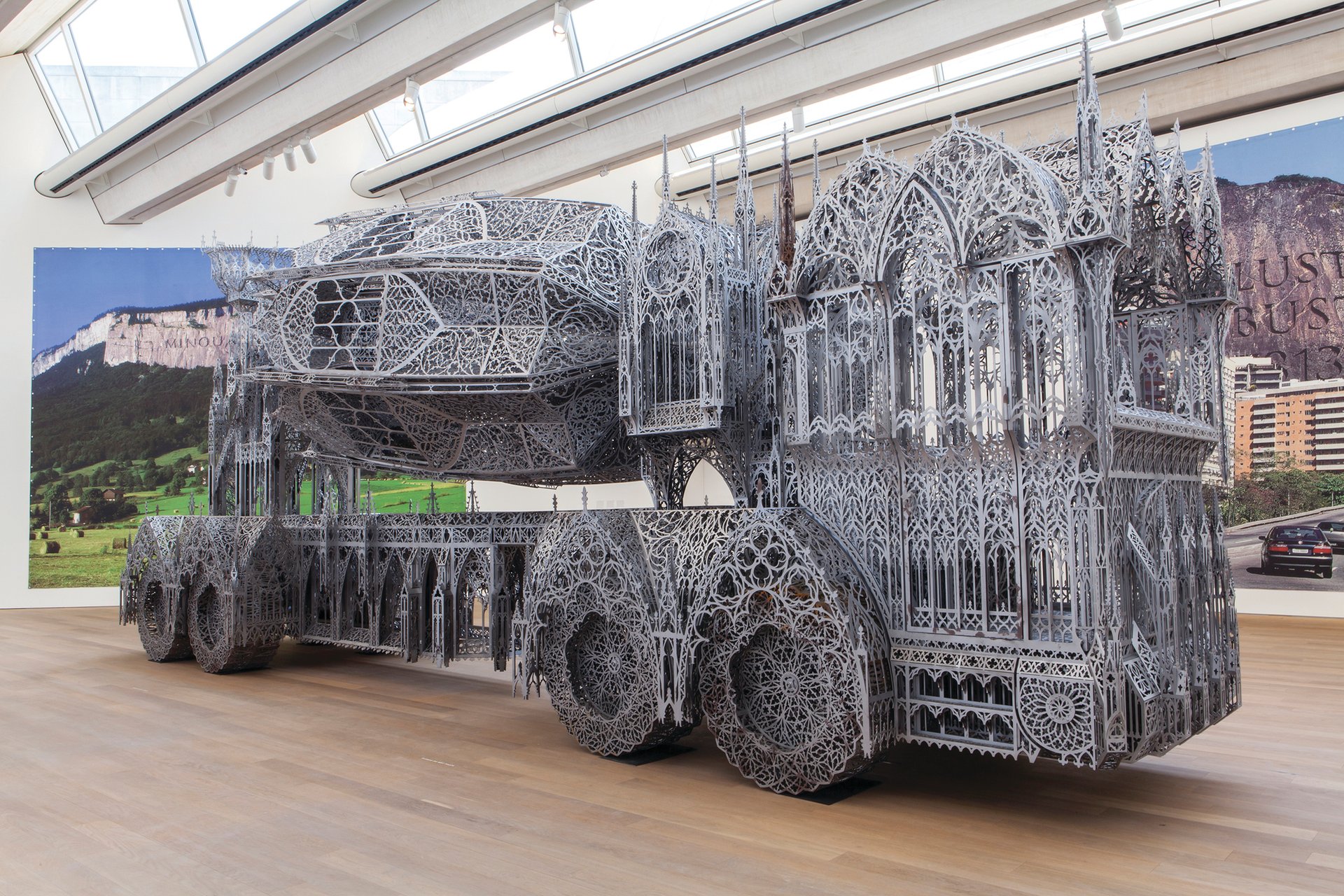

Gothic

Some of Delvoye’s most spectacular, and intricate, large-scale works from his Gothic series are included in the Basel show. These include Cement Truck (2012-16), a vast russet orange creation which, according to the exhibition catalogue, is “made of Corten steel plates which have been laser cut to reproduce neo-Gothic tracery and ornaments”. The filigreed work Concrete Mixer (2012) is another example of Delvoye’s work created in the skeletal, perfectly symmetrical Gothic style.

Bonds

Delvoye took the audacious step of selling bonds in Cloaca, which could be exchanged after a three-year period for vacuum-packed artificial excrement produced by the machine. “By selling bonds in his Cloacas and financing other projects through the sale of shares, by shamelessly promoting investment in art and actually demanding it of his collectors, he has stepped out into a world that is ostensibly ‘unartistic’ but that is actually very much au fait with art; after all, we all watch the art market,” say the scholars Roland Wetzel and Enrico Lunghi in the catalogue foreword. A preparatory drawing for Cloaca bond (2008) is on show.

Maserati car

An ornately decorated Maserati car dating from 1961 is also on display. “It’s the only time Maserati experimented with aluminium, a very soft metal, which was considered a material of the future back then, so a lot of major brands experimented with it at the time,” Delvoye says. “I got my hands on this original Maserati, which we shipped to Jakarta where Iranian assistants made very ornate, very Middle Eastern designs [on the car]. They emboss it with hammers, stamping very beautiful designs in the body work. It is like a new flying carpet. We want to compete with historical examples. Today you have so many tools at your disposal, but I don’t want to just copy, I want to compete.”