It is by some accounts the world’s biggest protest. Since November, tens of thousands of Indian farmers have driven their tractors towards New Delhi and are now camped out on the highways around its periphery. They refuse to leave until the government overturns a new set of agricultural laws they claim will deregulate crop pricing and devastate their earnings by exposing them to exploitation from large corporations.

Along New Delhi’s borders with the neighbouring states of Punjab, Haryana and Uttar Pradesh, the protest sites have turned into makeshift villages with their own schools, kitchens and hospitals. But with tractor queues stretching to around 25km, and with the technology-averse elderly making up a sizeable portion of the protestors, union leaders speaking on stages have been struggling to disseminate accurate and up-to-date information to the vast crowds.

The front page of the second edition of the Trolley Times, published in English © Trolley Times

This served as the impetus for a team of Indian artists, writers and agricultural workers to create the Trolley Times—a bi-weekly newspaper, now on its seventh edition, which aims to “voice the truth of the farmers' protest”.

Deriving its name from the trolley— the trailer of the tractor that farmers have now repurposed into mobile homes for the duration of the protest—the publication has a circulation of 7,500 and is printed in Hindi and Punjabi, with select editions also translated into English. Handed out at six demonstration sites, the newspaper is a mix of protest information and strategy, interviews with union and community leaders, as well as games, poetry and essays.

Artist duo Thukral & Tagra are behind the design of Trolley Times Courtesy of Thukral & Tagra

Behind the design of the Trolley Times are the Indian artist duo Jiten Thukral and Sumir Tagra, known collectively as Thukral & Tagra.

“It is a ritual act, that of opening a newspaper every morning and discussing events. Protestors need a purpose if they are to continue to fight,” Thukral says. “We are, of course, privileged and urban-dwelling, not farmers, and this is not our personal struggle. Our role here as artists is to help condense and capture a visual identity for the movement.”

The duo have been exploring agrarian issues in their native state of Punjab since 2012. This was around the time suicides among Indian farmers skyrocketed to epidemic levels, largely due to widespread crop failures and rising debt linked, in part, to climate change exacerbated drought.

Their most significant research project on this crisis was commissioned by the Yorkshire Sculpture Park (YSP), which led to a 2018 show on the traditional Indian style of wrestling kushti, practised among farming communities. At YSP, they invited visitors to attempt wrestling manoeuvres to understand how “farming families wrestle for their lives”, they say in an exhibition text which highlights the multitude of issues plaguing India’s farmers. These include agrarian policy failure, corporate strong arming, soil degradation from the overuse of pesticides and insufficient government intervention.

Women have turned up en masse to the protests © Gurdeep Dhaliwal / gurdeepdhaliwal.com

Many of these problems are now addressed in the pages of the newspaper, alongside what the duo describe as the “invisible voices” of the movement, such as that of Harinder Bindu, a 43-year-old female farmer union leader who crossed religious and class divides to encourage hundreds—if not thousands—of women to leave their villages and join the protest. “We want to shine a light on the lesser told stories of these protests—of the solidarity, gender equality and intergenerational co-operation at play here," they say.

Other marginalised groups such as immigrants and undocumented workers within the agricultural sector are also featured in specially themed editions of the paper that broach social issues as contentious as the caste system.

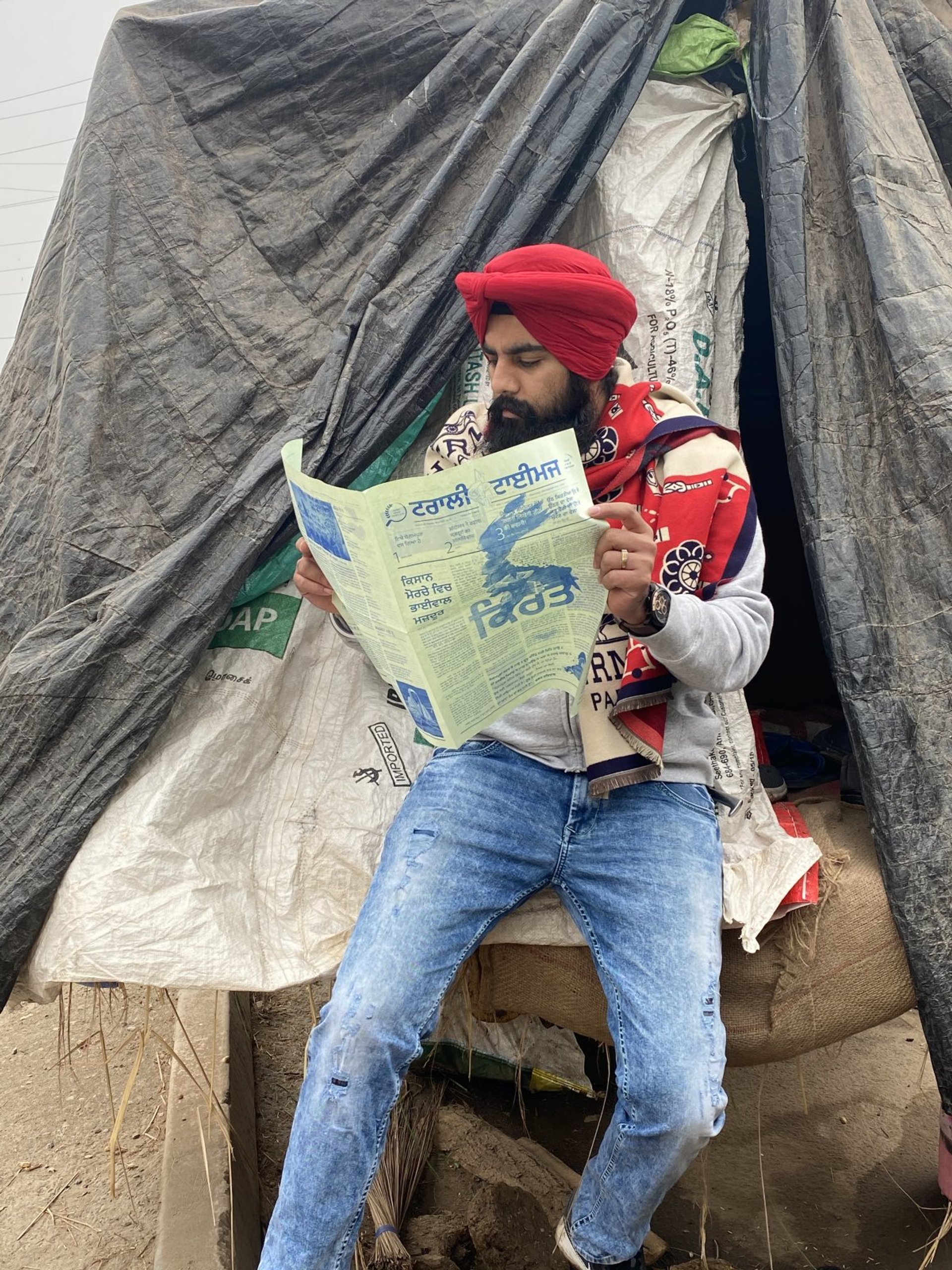

A copy of the Trolley Times read by a protestor © Gurdeep Dhaliwal / gurdeepdhaliwal.com

Most Indian media has largely ignored—if not outright denied—these narratives. Instead, farmers and their unions are often depicted as anti-nationalist, recalcitrant and greedy.

“The majority of our major news channels are billionaire-owned and government-leaning. You must look elsewhere for the real story,” says the Punjabi documentary photographer Gurdeep Dhaliwal, a founding member of the Trolley Times team. “They don’t show the aspects of the protests that would encourage the middle classes to join the farmers side. There’s no politics and violence here. But they know that if the middle class joins the farmers, this will become a very different protest.”

“Land is everything they have, if you’re taking that away they’re going to do everything to save it”Gurdeep Dhaliwal, documentary photographer

Dhaliwal has documented the protests on the ground since they first began in Punjab last August via his Instagram page @_kirrt_. He says that the farmers' spirit has been resolute since its inception. “Land is everything they have, if you’re taking that away they’re going to do everything to save it.”

Each edition of the paper also features a dedicated section to the “martyrs” who have died since the protests began from a combination of cold weather, illness and—in at least four reported cases—suicide in support of the cause. According to various farm unions, around 78 deaths have occurred during the farmers’ protests from 26 November to 6 January.

Streamlining or selling out?

These protests come at a time when coronavirus has caused many urban workers to migrate back to their villages, swelling the already massive portion of the 1.3 billion Indians who primarily depend on agriculture for their livelihood—estimated at more than 60 percent.

Yet the sector still accounts for only around 15 percent of the country’s economic output. It is this sluggish performance which the laws ostensibly seek to combat. At their core, they will defederalise and streamline what Prime Minister Narendra Modi asserts is a needlessly complicated system based around auction markets known as mandis.

Under Modi's ambitious plans to double the economy by 2024, sectors such as agriculture must loosen regulations and open up to private interests. But farmers fear that disposing of protective systems will leave them vulnerable to the volatility of free market economics. And when a crash comes, it will be them, rather than the private companies, who will pay the heaviest price.

Earlier this month, the Indian Supreme Court put the new laws on hold and is trying to strike an agreement between the farmers' unions and the government. Every attempt has so far been unsuccessful, with the farmers refusing anything short of a complete repeal of the laws. A tenth round of talks is scheduled for next month.

Farmers say they will refuse anything short of a complete repeal of the laws © Gurdeep Dhaliwal / gurdeepdhaliwal.com

Tomorrow, India celebrates one of its biggest national holidays, Republic Day. And as the global media turns its eye to the military processions set to take place in the Delhi, farmers have planned a rival tractor rally around the outer highways to publicise their cause. Handed out to onlookers will be the Trolley Times’s eighth edition.

“We hope the Trolley Times becomes a case study for an alternative type of media”, Thukral says. "Compared to corporate owned platforms like Instagram and others where fake news is rife, one wonders how you can develop faith in anything true these days.”

“There is strength in numbers. And we certainly have them"Thukral and Tagra, artists

Available on a Google drive, the newspaper is free to print anywhere and is now distributed across India as well as locations as far as Sydney, Australia. The duo also runs the website kisanekta.in, an open-source archive which acts as an image bank for the Trolley Times.

Thukral &Tagra, who are currently interviewing farmers for the second part of their 2018 documentary film Kisan Ekta Morcha, cite the 1976 Hindi language film Manthan as another major influence. The film told the story of the Milk Revolution, a period when India transformed itself from a milk deficient country to the world's greatest dairy producer. Much like the Trolley Times, the film embodied solidarity among agricultural workers; it was crowdfunded by 500,000 farmers, each of whom donated two rupees.

“There is strength in numbers. And we certainly have them", they say. "It’s high time those in power take notice. Everyone else has protested against this government—Muslims, women, student, farmers. The only thing left are the corporations.”