Anti-immigrant sentiment in China is on the rise. In recent months there has been a surge in online vitriol towards Muslim refugees, while nationalists with openly racist views have become more vocal. One community under fire is the African immigrant population in Guangzhou, a major port city with around 13 million inhabitants, on the Pearl River, 120km north-west of Hong Kong.

In March, at a Communist Party Congress in Beijing, Pan Qinglin, a representative from the northern Chinese municipality Tianjin, advocated “solving the African social problem” in Guangzhou through mass deportation. He claimed that half a million Africans have moved to the southern trading city (academic estimates put the number at tens of thousands) and accused them of drug trafficking and sexual assault. He also warned that Africans are likely to bring Aids and Ebola to China. He later told the media that African immigration and its impact on Chinese racial purity will cause Chinese civilisation to collapse. Although it did not pass, Pan’s proposal garnered significant online support.

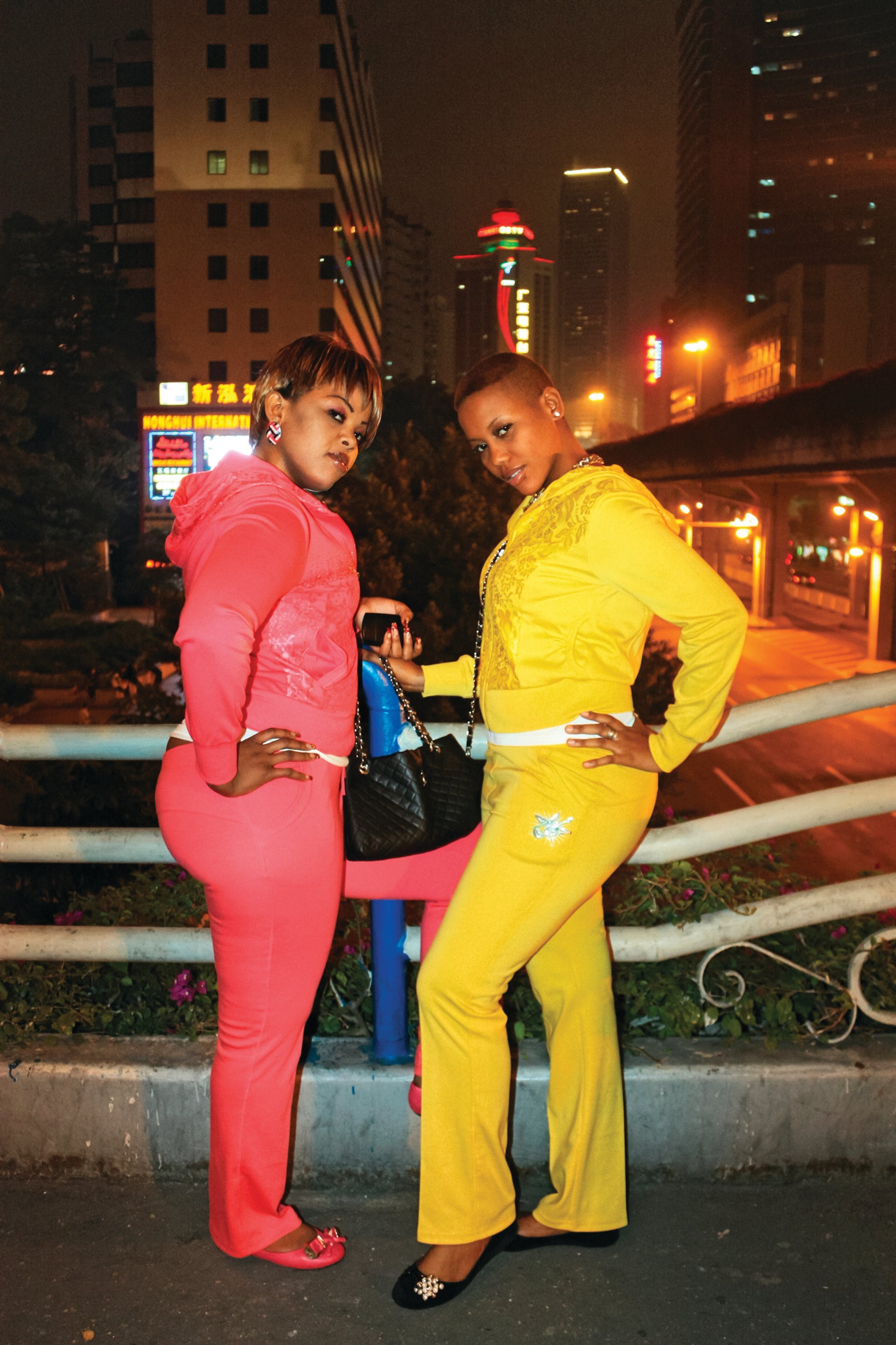

This racism is not new, says Daniel Traub, a US photographer who has documented the African residents of Guangzhou, many of whom are successful traders, in collaboration with two itinerant Chinese portrait photographers, Wu Yong Fu and Zeng Xian Fang. Traub’s portraits, which are on display in the exhibition Here’s Looking at You! at the Shanghai Centre of Photography (until 25 June), were taken on a pedestrian bridge in Xiaobei, an ethnically diverse neighbourhood of the city, over several years. “Perhaps people feel more justified in [expressing racist opinions] because of Trump and Brexit,” Traub says.

An official crackdown on Africans in Xiaobei began in late 2014, Traub says, as the Ebola epidemic took hold in West Africa. “The Chinese authorities used that as an excuse to [target] Africans in Guangzhou; informal commerce was curtailed, and from what I understand, the African population there decreased quite a bit.” Despite the official stance, the Chinese inhabitants of Guangzhou are more “open-minded” than the Chinese elsewhere in the country because they live side by side with African immigrants and interact with them regularly, Traub says.

The Africans in Guangzhou feel that “they have a right to be in China because there are so many Chinese doing business and living in Africa…why shouldn’t there be a reciprocal presence of these populations in China?” Traub asks. “China’s resistance to immigration… seems a bit hypocritical and in the long run, perhaps even self-defeating. It seems to me that China’s influence and reach can only go so far if it doesn’t allow the mainland itself to become more cosmopolitan and diverse.”

“China has yet to start the conversation about the condition and rights of minority communities in the country,” says the Shanghai-based curator and critic Zhang Hanlu. That conversation is “partially suppressed by the state [because] a homogeneous population is more easily controlled… look at how the government treats migrant workers in Beijing: it restricts their [ability to] work, live and have their children educated in the city”, and so they leave. But “more global migrants are coming to China’s cities from Southeast Asia and Africa, and I’m interested to see more light cast on these groups; they are foreigners, but very different to the immigrants from white developed countries that we are used to”, Zhang says.

• Daniel Traub’s portraits of Africans in Guangzhou are published in Little North Road, Africa in China (Kehrer Verlag, 2016)