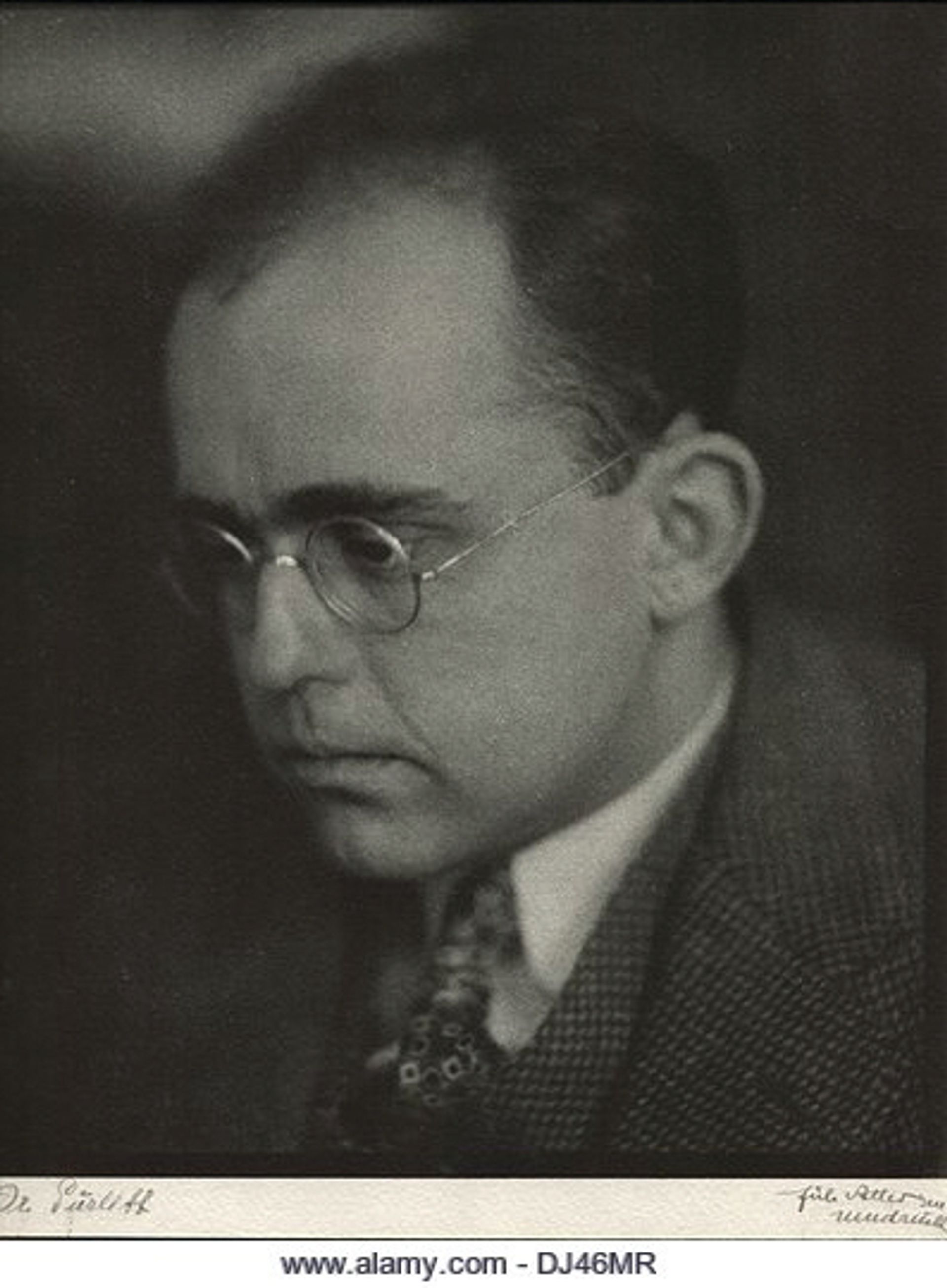

Cornelius Gurlitt’s surprising decision to bequeath his controversial collection to the Kunstmuseum Bern has triggered a new impetus for provenance research in the Swiss capital. The elderly recluse, who hoarded Nazi-looted art for decades in his Munich apartment and Salzburg home, unexpectedly named the museum as the sole beneficiary of a will written weeks before he died in May 2014.

Gurlitt’s legacy comprised more than 1,500 works of art, including paintings by Pablo Picasso, Henri Matisse, Claude Monet, Max Beckmann and Otto Dix. He had inherited the trove from his father, Hildebrand Gurlitt, a dealer for the Nazis who bought works that had been plundered from Jews or sold by Jews desperate to leave Germany.

The museum took possession of the first pieces from the collection in the first week of July. It had already begun laying the groundwork to manage the bequest. The art historian Nikola Doll was appointed in May to run a provenance research team of four and the museum held a conference on Nazi-looted art in collaboration with the University of Bern in early June.

“It is impossible to separate the Gurlitt collection from […] the debate about Nazi-looted art,” says Nina Zimmer, the director of the Kunstmuseum Bern. “Gurlitt sparked […] international attention on the Swiss politics of provenance research.”

At the time, the Kunstmuseum Bern hesitated before accepting Gurlitt’s art, describing it as “a considerable burden of responsibility” that carried “a wealth of questions of the most difficult and sensitive kind”. International groups such as the World Jewish Congress drew attention to Switzerland’s spotty record in restituting Nazi-looted art.

Cornelius Gurlitt’s cousin contested his will, postponing the museum’s inheritance until December 2016. To finance the court costs incurred by her challenge, the museum is now planning to sell his Salzburg and Munich properties.

“I am glad the museum’s board took on this responsibility,” Zimmer says. The bequest, she says, has not only brought about a shift in attitude but also led to new policies.

One result of the debate was the federal government’s decision to offer museums grants for provenance research last year. It allocated more than SFr900,000 to ten institutions, including SFr200,000 for the Kunstmuseum Bern. Private donors, including the Rudolf and Ursula Streit Foundation and the Ursula Wirz Foundation, have supplemented this with their own contributions. The funding so far is enough to support provenance research for two years. “We have to keep fighting for long-term financing and a long-term structure,” Zimmer says.

The museum is using the money to digitise its archives from the era of the Third Reich and make them accessible to researchers. It is also investigating and publishing the provenance of its own collection.

Meanwhile, the University of Bern’s Institute of Art History is in talks with potential sponsors for a new teaching post for provenance research—something Zimmer says is urgently needed given the current dearth of specialists in Switzerland. The Gurlitt collection remains in Germany for now, and the Kunstmuseum will only take possession of art with a provenance that is free from suspicion of Nazi looting. The remainder will continue to be investigated by the Gurlitt Provenance Research Project at the Magdeburg-based German Lost Art Foundation, at least until the end of this year.

Parallel exhibitions of the collection, called Dossier Gurlitt, are planned to open at the Kunstmuseum Bern and the Bundeskunsthalle in Bonn, Germany, in November. The Bern show will focus on works seized from German museums as part of the Nazis’ merciless campaign against art they considered “degenerate”. The Kunstmuseum is offering visitors a preview at the Gurlitt Workshop, where the works will undergo conservation before the exhibition. Guided tours are due to start on 18 August.

Gurlitt by numbers Among 1,566 works:

Two paintings by Jean-Louis Forain have been identified as looted by the Nazis in France but still contain provenance gaps requiring further research.

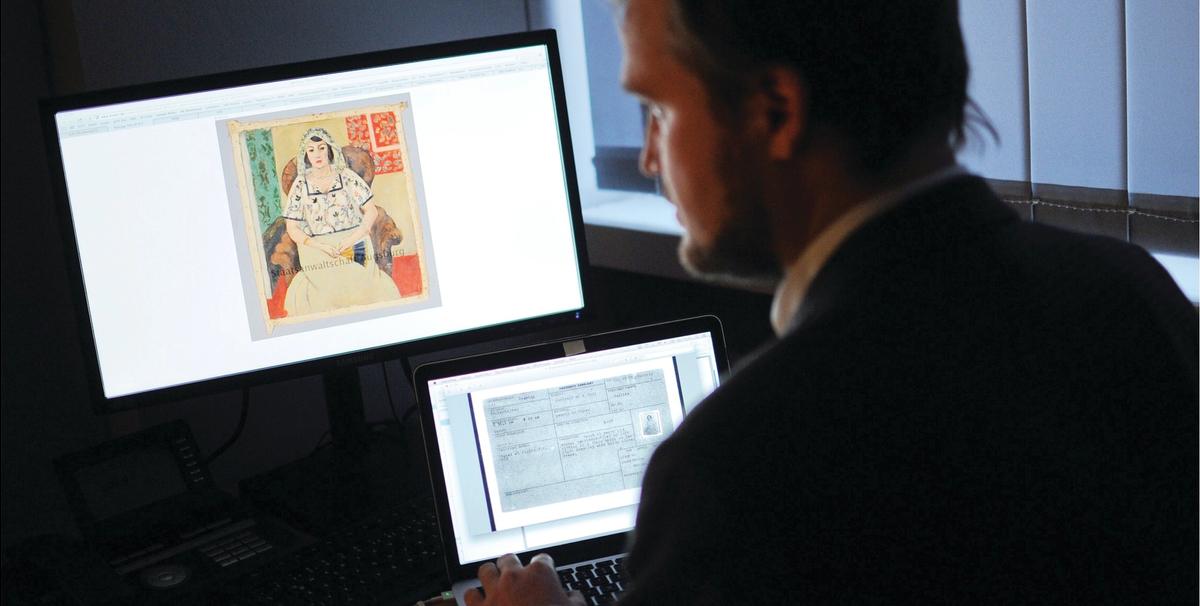

Five pieces have been identified as Nazi-looted. Four of these have been returned to the heirs of the original owners, including Max Liebermann’s Two Riders on the Beach (1901) and Matisse’s Seated Woman (1921).

55 pieces have been excluded from research because they were mass produced—for example, pages from a calendar.

As of 14 January 2016, 231 works were identified by the Schwabing Art Trove taskforce as “degenerate” art seized by the Nazis from German museums and are therefore not liable for restitution. Of these, 118 were acquired by the museums before 1933. They include works on paper by George Grosz, Oskar Kokoschka and Wassily Kandinsky, and are likely to be among the first works sent to Bern.

278 are works by or dedicated to Gurlitt family members, and therefore free of suspicion. They are likely to be in the first batch of works travelling to Bern.

1,039 works are undergoing research by the German Lost Art Foundation in Magdeburg.