The German government’s advisory panel on Nazi-looted art has called on the city of Cologne to return a watercolour by Egon Schiele to the heirs of Heinrich Rieger, a Jewish Viennese dentist and art collector who was murdered at Theresienstadt concentration camp.

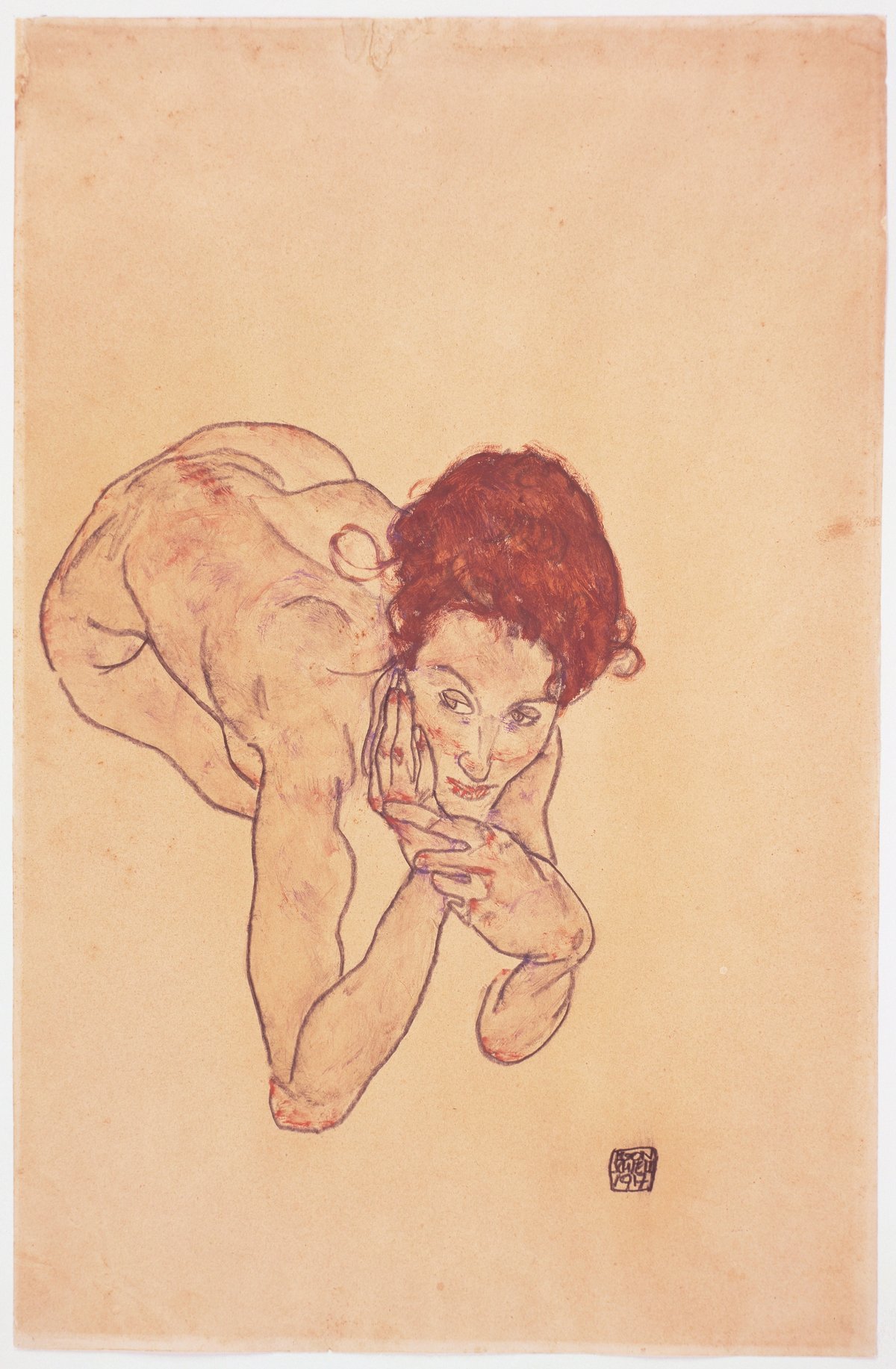

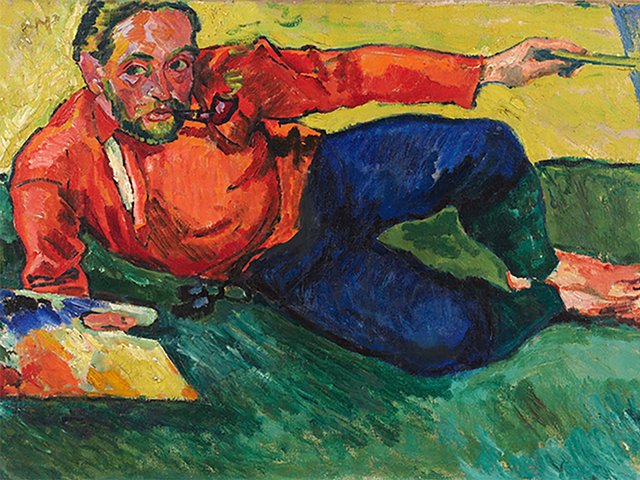

The 1917 work in watercolour and pencil, titled Crouching Female Nude, (Kauernder weiblicher Akt in German) was donated to the city of Cologne in 1966. It is not known when it disappeared from Rieger’s collection. He began exchanging dental treatment for drawings and paintings with young Austrian artists in about 1900. Over the following three decades, he collected around 800 works by artists including Oskar Kokoschka and Gustav Klimt. A whole room of his home—which he opened for public viewing 12 times a year—was devoted to Schiele, one of his patients.

After the Nazis annexed Austria, Rieger’s son Robert managed to escape via Paris to New York. Rieger and his wife had many possessions confiscated and were forced to sell others, including their art. Berta Rieger wrote to her son in 1939 saying: “Just one thing is terrible, we have to sell almost all our possessions at fire-sale prices.” They were deported to Theresienstadt, where Rieger died in 1942; Berta was transferred again to Auschwitz in 1944 and was probably gassed on arrival there.

The exact circumstances of the loss of Crouching Female Nude from Rieger’s collection could not be established. Cologne had argued it was possible Rieger sold the work before the Nazis annexed Austria and began persecuting Jews and seizing their art collections. But the panel said the evidence suggests Rieger sold only a handful of works before 1938 and a vast majority of his sales “took place after March 1938 as a consequence of the pressures of Nazi persecution.” Its recommendation to restitute the work was unanimous.

Yilmaz Dziewior, the director of the Museum Ludwig, said the museum was grateful to the commission for its work and thanked Rieger’s heirs for their patience. The city of Cologne is expected to approve the restitution next month.

“This case has occupied all those involved for a long time and the fact that it was not possible to trace fully the fate of Crouching Nude—as is so often the case with the art collections of victims of Nazism—was disappointing for us at the Ludwig Museum,” Dziewior said. “We are relieved that there are now prospects for a fair and just solution with the return of the work to the family.”