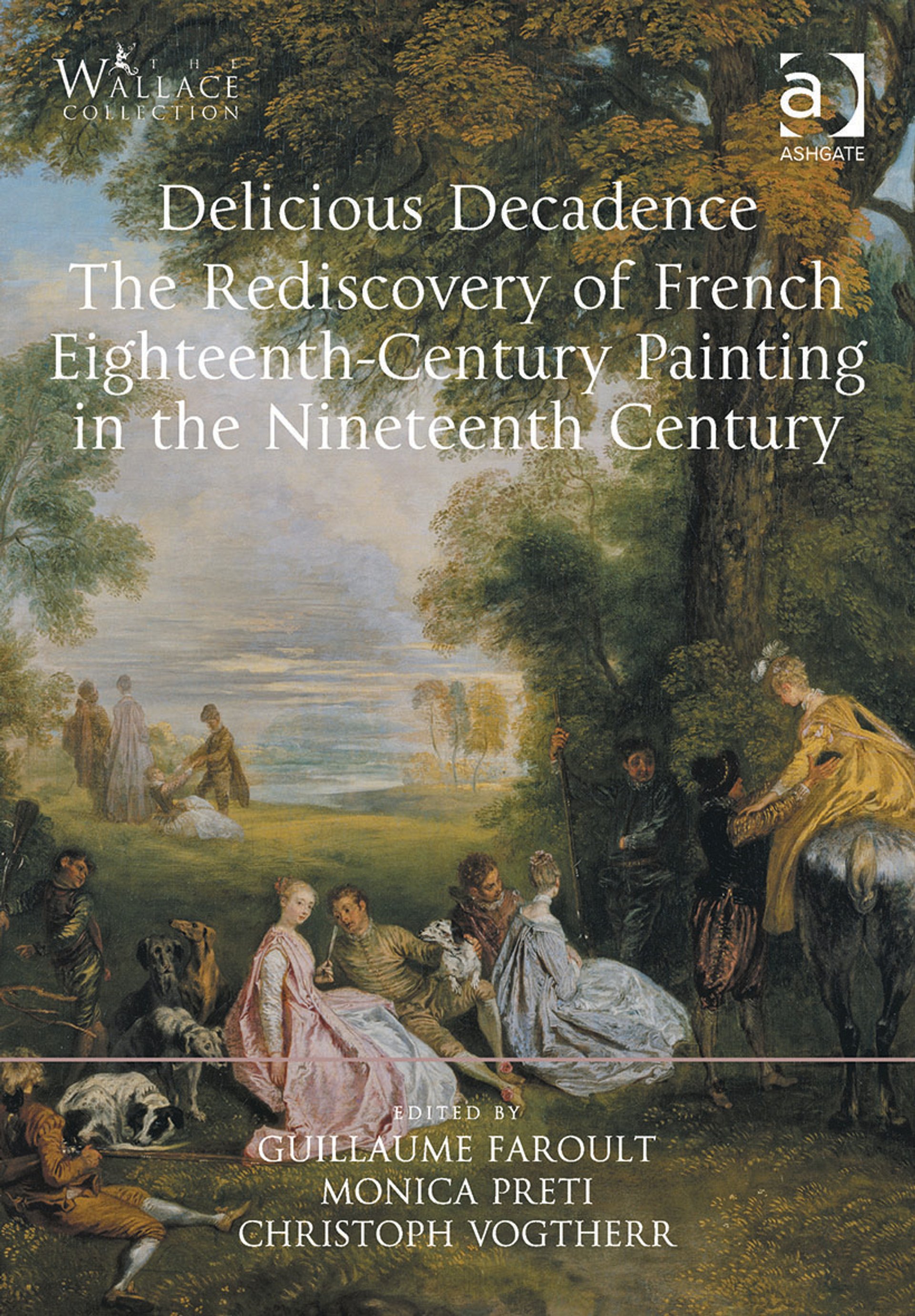

The ten papers assembled in Delicious Decadence: the Rediscovery of French Eighteenth-Century Painting in the Nineteenth Century, were delivered at an international conference at London’s Wallace Collection in May 2008. They were occasioned by an exhibition devoted to the collector Louis La Caze (1798-1869). His bequest to the Louvre of 583 paintings, many by 18th-century French artists, gave the seal of approval to a slow process by which the art of 18th-century France, or at least works by a handful of its masters, entered the official canon. The authors trace that process, identifying early critics, collectors and curators whose pioneering efforts led to paintings by Watteau, Chardin, Boucher and Fragonard, returning at mid-century to public appreciation. Jacques-Louis David’s stern revolution in art had relegated them to the more frivolous margins.

The title of the volume comes from a resonant phrase, une décadence délicieuse, from the Goncourt brothers’ L’art du dix-huitième siècle. It also succinctly suggests that what was revived in the mid-19th century was a narrow strand of the 18th-century tradition, the fête galante and related celebrations of French refinement and sensuality in a Rococo mode. The bourgeois realism of Chardin, second only to Watteau in the enthusiasm he provoked among connoisseurs, was also celebrated. It was seen to break with academicism based on superannuated Italian models, and to introduce a refreshing, truly French spontaneity into picture-making. Few, if any, references were made at the time to the dour Jansenist allegories of a Jean Restout, say, or indeed to religious imagery of any kind.

Paris and London

It would seem to be a tale of two cities. The energy of La Caze’s collecting in Paris, and of the Goncourts’ pen, was matched by the single-minded pursuit of 18th-century treasures by Paris-based Briton the Marquess of Hertford (1800-1870), whose collection would form the basis of the Wallace Collection. In his contribution here, Jon Whiteley points to other early London enthusiasts. Indeed, as appreciation of the Rococo mounted, French connoisseurs were heard to lament that many of the finest paintings had slipped into English hands. As often as not these collectors were primarily interested in the decorative arts; paintings served to illustrate for them a uniquely refined way of life in which Sèvres porcelain, collected with maniacal enthusiasm and at high prices, was by far the most desirable material manifestation.

Stephen Duffy traces the impact the opening of the Wallace Collection in 1900 had on English taste, and the amusing expressions it provoked of deeply ingrained middle-class mistrust for suave Parisian ways. Humphrey Wine points out that the tantalising hope the Wallace Collection might one day come to London, indeed might come to the National Gallery, saved that parsimonious and Italophile institution a great deal of money; for generations it simply did not bother to acquire in the field. And when the collection went to its own home in Manchester Square rather than to Trafalgar Square, the National tacitly treated the Wallace as a convenient outpost, not bothering to collect French 18th-century art for several generations more.

Berlin’s role

In the most provocative essay here Christoph Vogtherr demonstrates that almost as important as Paris or London in the revival of French 18th-century painting was the role played by Berlin. Frederick the Great had assembled a magnificent collection of Rococo works in the 18th century. The pictures were among the chief adornments of his Francophile court, not least among them Watteau’s L’Enseigne de Gersaint. As enthusiasm for things dix-huitième mounted in the 19th century, the collection became a tool of diplomacy, lent abroad, or not lent, as the exigencies of Realpolitik dictated.

The French felt increasing embarrassment that the greatest collection of such works should grace the Prussian capital while little like it was to be seen in the Louvre. They reacted in no less political a manner. Two French scholars turned their efforts to proving that the Berlin Enseigne was merely a copy of a version that remained safely on French soil. That they were wrong was proven easily enough. But it was not the first time that 19th-century politics had shaped perceptions of 18th-century art. As Frances Suzman Jowell shows, before that the socialist Théophile Thoré, writing as Willem Bürger, had argued passionately that the fête galante tradition was a manifestation of liberalism and liberty. It represented the moment French art had freed itself of foreign aesthetic domination.

Such hints of the wider implications attendant on the Goncourts’ “delicious decadence” render this volume surprising and important.

Christopher Riopelle is the curator of post-1800 paintings at the National Gallery, London

Delicious Decadence: The Rediscovery of French Eighteenth-Century Painting in the Nineteenth Century

Christoph Vogtherr, Monica Preti and Guillaume Faroult, eds

Ashgate, 210pp, £55 (hb)