The latest proposals for artworks to occupy the Fourth Plinth in Trafalgar Square in London were unveiled today. The six maquettes for the works—by the artists Nicole Eisenmann, Samson Kambalu, Goshka Macuga, Ibrahim Mahama, Teresa Margolles and Paloma Varga Weisz—are on view at the National Gallery, a stone’s throw from the plinth.

The new ideas, two of which will be chosen to occupy the plinth in 2022 and 2024, are being shown amid sharp focus on London’s historical monuments, due to the UK government’s attempts to influence academic and heritage debates relating to British history following the renewed focus on slavery and colonialism in the wake of recent Black Lives Matter protests.

“The fourth plinth has always sat, I think, at this intersection of popularity and sometimes political comment and thought,” says Ekow Eshun, the chair of the Fourth Plinth Commissioning Group. “In part, that's a lot to do with its location, with its place in Trafalgar Square. Our position is that the Fourth Plinth as a programme is an ongoing conversation with the city—about the role of art, but really also about the role of society. At times, those conversations become more heightened, as they have done over the past year. But the point about the project as a whole is that it continues to have this conversation through these different highs and lows in different periods of time.”

Among the more directly socio-political works in this year’s selection is Samson Kambalu’s Antelope, which appears to be a relatively conventional bronze sculpture from one angle, but in fact depicts the pan-Africanist John Chilembwe’s defiant gesture of wearing a hat, which was forbidden in Nyasaland, modern-day Malawi, under colonial British rule. A smaller sculpture of the European missionary John Chorley would stand alongside Chilembwe.

Teresa Margolles, 850 Improntas (850 Imprints) (2021) © James O Jenkins

Meanwhile, Teresa Margolles’s proposal is to show 850 plaster masks depicting and made by trans people in London in a cubic structure inspired by form of a Tzompantli, a Mesoamerican skull rack “used to display war captives or sacrifice victims”, according to the official statement. Both a gesture of defiance and a reflection of overlooked or under-represented communities in public art and monuments, Margolles’s plaster masks would erode as a result of London’s weather and ultimately disappear.

Justine Simons, London’s deputy mayor for culture and the creative industries, says that artists approaching the commission “have never shied away from exploring difficult, provocative” issues. She adds: “It feels like a really bold and confident move for London, as a world class city, to have been commissioning thought-provoking progressive, brilliant contemporary art, in the heart of this grade-one listed heritage space for two decades. It's bold and it says how confident we are as an international, diverse, creative city. And it's more important than ever.”

Eshun says that the works “are potentially enduring in that they can look beyond the moment. In practical terms they do, because one of these works will go up on the plinth in 2024. So this is less about the current political moment, and more about the larger sense of art's relationship and art's conversation with the city and its people."

And that dialogue has “got more international as we've gone on”, Eshun says, “because we're looking to find artists from all around the world who can be part of that ongoing conversation”.

Members of the public can have their say on the proposals online, before the Fourth Plinth Commissioning Group—which includes Eshun and Simons alongside the artist Jeremy Deller, the director of the Showroom in London, Elvira Dyangani Ose and the broadcaster Jon Snow, among others—decides on the two winners of the commission in late June. The maquettes are on view at the National Gallery until 4 July.

The plinth has strict “formal strictures” in that it has finite dimensions, but, Eshun says, “there's the thing that is in the middle of Trafalgar Square, the most popular historical public space in London, it's in front of the National Gallery, it's looking out to Parliament. There’s a range of conversations that are taking place that the artists have to bear in mind, and I think the successful works on the plinth are able to synthesise all these different settings and contexts, and offer something that has clarity, imagination, ambition. I think each of these [proposals] in different ways, has the capacity to do that."

From vulnerability to defiance, space rockets to grain silos: the six Fourth Plinth proposals

Justine Simons, deputy mayor for culture and the creative industries in London, on the contenders for the two commissions

Nicole Eisenman, The Jewellery Tree © James O Jenkins

Nicole Eisenmann, The Jewellery Tree

An enlarged jewellery stand, of the kind you find on a dressing table, with a cluster of often unexpected objects on and around it, including a rolled up carpet, flatbreads and potatoes, a drum that seems to be puking black liquid, and the medals of Lord Nelson, who stands on his famous column nearby. “It is this mix of sentimental things, precious things, but also everyday things. So you'll see a used coffee cup lid as well as a medal. And it's this idea of making the everyday monumental. But again, as all of them, it’s riffing off Trafalgar Square, and the heritage in the square. And that's what's great about the site-specific nature of the Fourth Plinth.”

Samson Kambalu, Antelope © James O Jenkins

Samson Kambalu, Antelope

A recreation of a 1914 photograph of the pan-Africanist John Chilembwe and the European missionary John Chorley in bronze. The picture was taken under British colonial rule in Nyasaland, as Malawi was then known. “It’s an extraordinary story of how a hat became a symbol of defiance and resistance against colonial rule,” Simons says. “So what you'll see is two bronze statues. And one of the statues, John Chilembwe, is outsize—super-size—wearing a hat. And you look at it, and you think that's a bronze statue, we recognise that, there's lots of Victorian bronze statues around. But if you look a bit closer, you realise that it is this really powerful symbol of resistance and defiance, because at the time, in the 1900s, it was—incredibly—illegal for Black people to wear a hat in the presence of white people.” Kambalu moved the hat “in order to really amplify the hat so it looks even bigger”, Simons says. “Chilembwe was killed by the colonial police, for fighting for equality. And in a moment where we're looking to redress diversity in the public realm, this is a powerful story that people need to know about.”

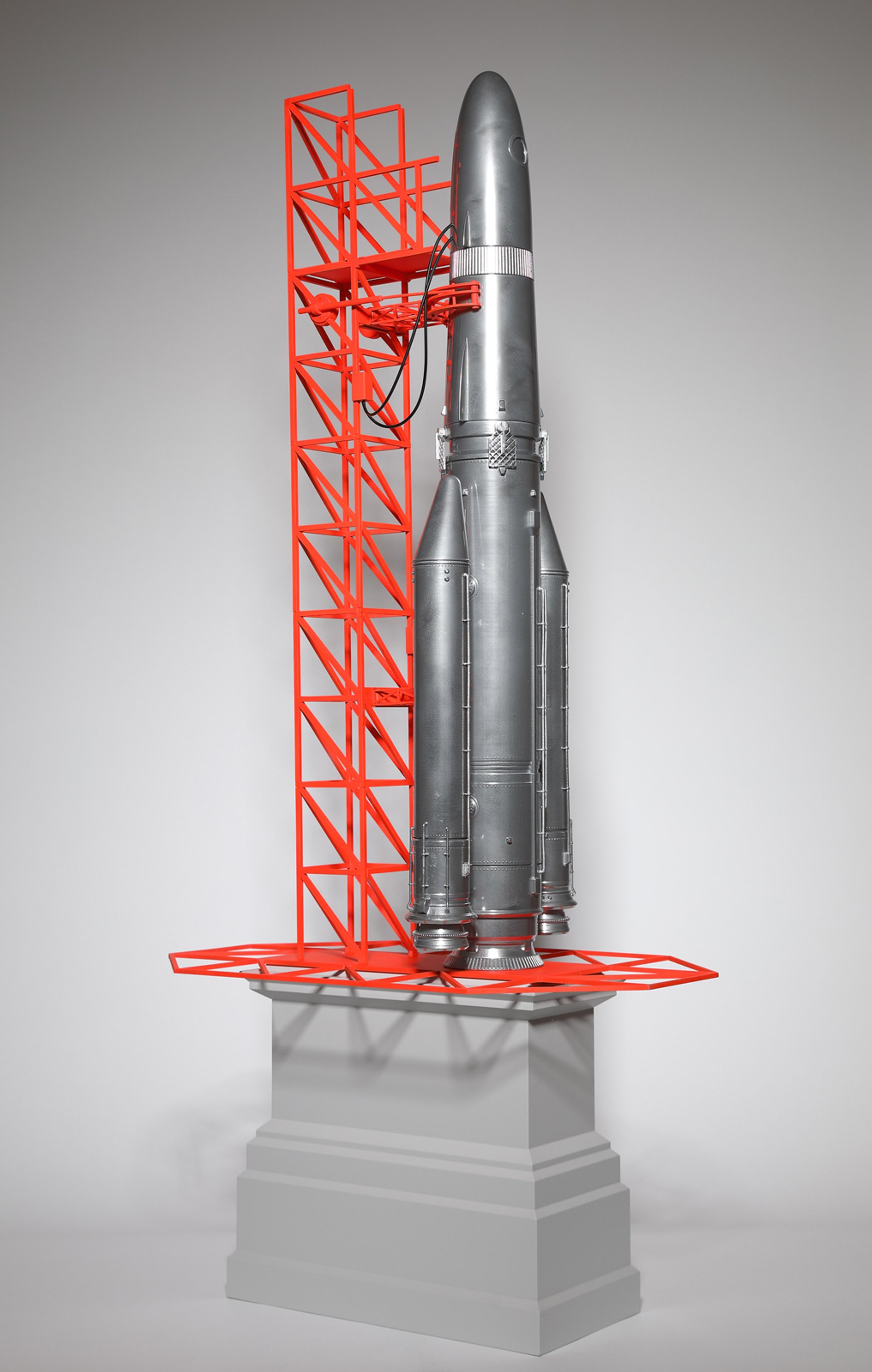

Goshka Macuga, GONOGO © James O Jenkins

Goshka Macuga, GONOGO

A silver rocket, with a distinctively retro-space age shape, sits on a bright orange launcher which evokes Modernist geometric sculpture. “The rocket will be massive,” Simons says, “it's really big. And I think the artist has talked about looking into the skies, looking into space, to gain some perspective on our lives. That is an idea that resonates today, more than ever.”

Ibrahim Mahama, On Hunger and Farming in the Skies of the Past 1957-1966 © James O Jenkins

Ibrahim Mahama, On Hunger and Farming in the Skies of the Past 1957-66

The latest in a series of works in which Mahama explores the Brutalist grain silos built by Eastern European architects in a utopian spirit in post-colonial Ghana, only to become abandoned relics, and symbols of the dashing of many of the hopes of early independence. Mahama’s proposal features a reconstruction of one of the silos in Tamale, his hometown, consumed with plants. “[The silos] were commissioned in the 1960s in Ghana,” Simons says, “and they never really got to fulfil their true potential, their intended function, because the President [Kwame Nkrumah] was very quickly overthrown in the 1960s. These incredible Brutalist structures are all around the country. And what you can see is how the ecosystem has grown around them. So the artist has been to visit lots of them and says that they've got plant life, there's bats, there's frogs, there's birds. Again, there's something about the pandemic there, isn't there? Where humans have retreated from urban space, and animals and plants have taken over.”

Teresa Margolles, 850 Improntas (850 Imprints) (2021) © James O Jenkins

Teresa Margolles, Teresa Margolles, 850 Improntas (850 Imprints) (2021)

A cuboid form atop the plinth with 850 plaster masks in a grid, cast from the faces of trans people in London. “This piece is really powerful,” Simons argues. “It's a monument to the trans community. There's a lot of conversation, isn't there, about how we need to represent more of our stories, and we need to represent more of society in our public realm. She's going to work with the London trans community, she'll cast their faces, and they'll literally be able to see themselves in the artwork. It's based on the death-walls that you saw in ancient times, where people were sacrificed for the gods. So you see these walls of skulls, effectively. So it has a nod to that. And in Mexico, where she's from, there have been lots of murders and deaths in the trans community. But she talks about this as a monument to the living. This is defiance, it's a wall of resistance, she says. This is all about the living and vibrant and fantastic trans community in London.”

Paloma Vargas Weisz, Bumpman for Trafalgar Square © James O Jenkins

Paloma Varga Weisz, Bumpman for Trafalgar Square

A figure that Varga Weisz has returned to in her work, partly inspired by the 16th-century German Wundergestalten tradition, where extraordinary human anatomies were depicted in pamphlets. The figure sits on a log that extends far beyond the footprint of the plinth. “You can see the Bumpman, a bronze piece, with all his vulnerabilities revealed on the outside,” Simons says. “And the artist is talking about how Trafalgar Square is all about the bronze stiff upper-lip, and here we have a more truthful picture. But he's contemplative, he’s looking to the skies and he's okay with his bumps.”