Two of the most famous pieces of Land Art—Robert Smithson's Spiral Jetty (1970) and Nancy Holt's Sun Tunnels (1973-76), each sited remotely in the Utah landscape—are more widely known through photography, writing and legend than firsthand experience. Continuing the late couple’s investigation of places on the planet at once real and imagined, the Holt/Smithson Foundation has just invited five contemporary artists—Tacita Dean, Renée Green, Sky Hopinka, Joan Jonas, and Oscar Santillán—to develop a proposal for a new work that will use an uninhabited island in Maine, purchased sight-unseen by Smithson and Holt in 1971, as a point of departure.

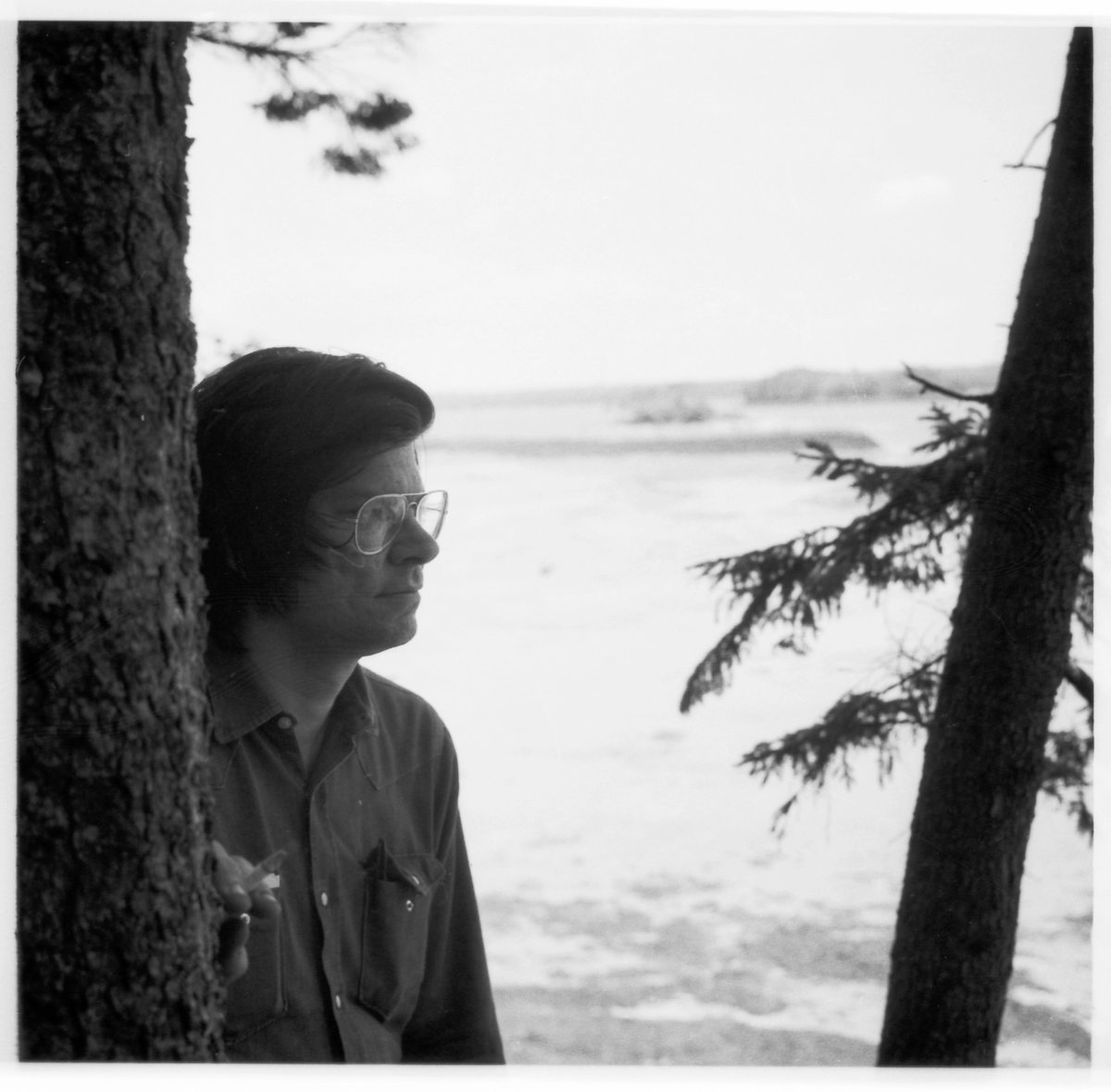

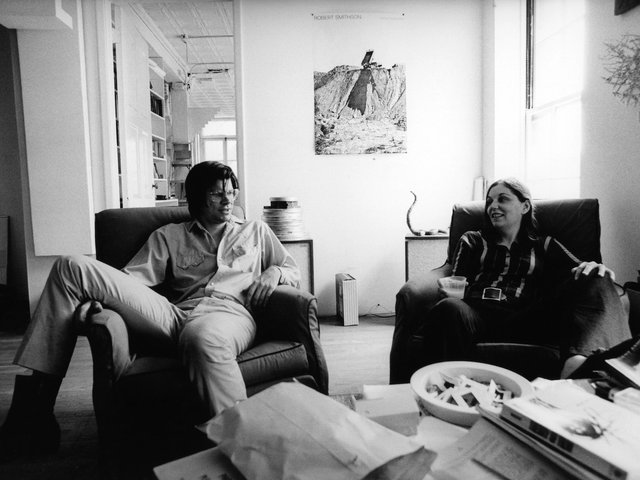

“Smithson was quite obsessed by islands, being places where you could really see geological history changing,” says Lisa Le Feuvre, the executive director of the artist-endowed foundation inaugurated in 2018 to kindle and expand the creative legacies of Smithson, who died aged 35 in a plane crash while surveying another potential site in 1973, and Holt, who died aged 75 in 2014.

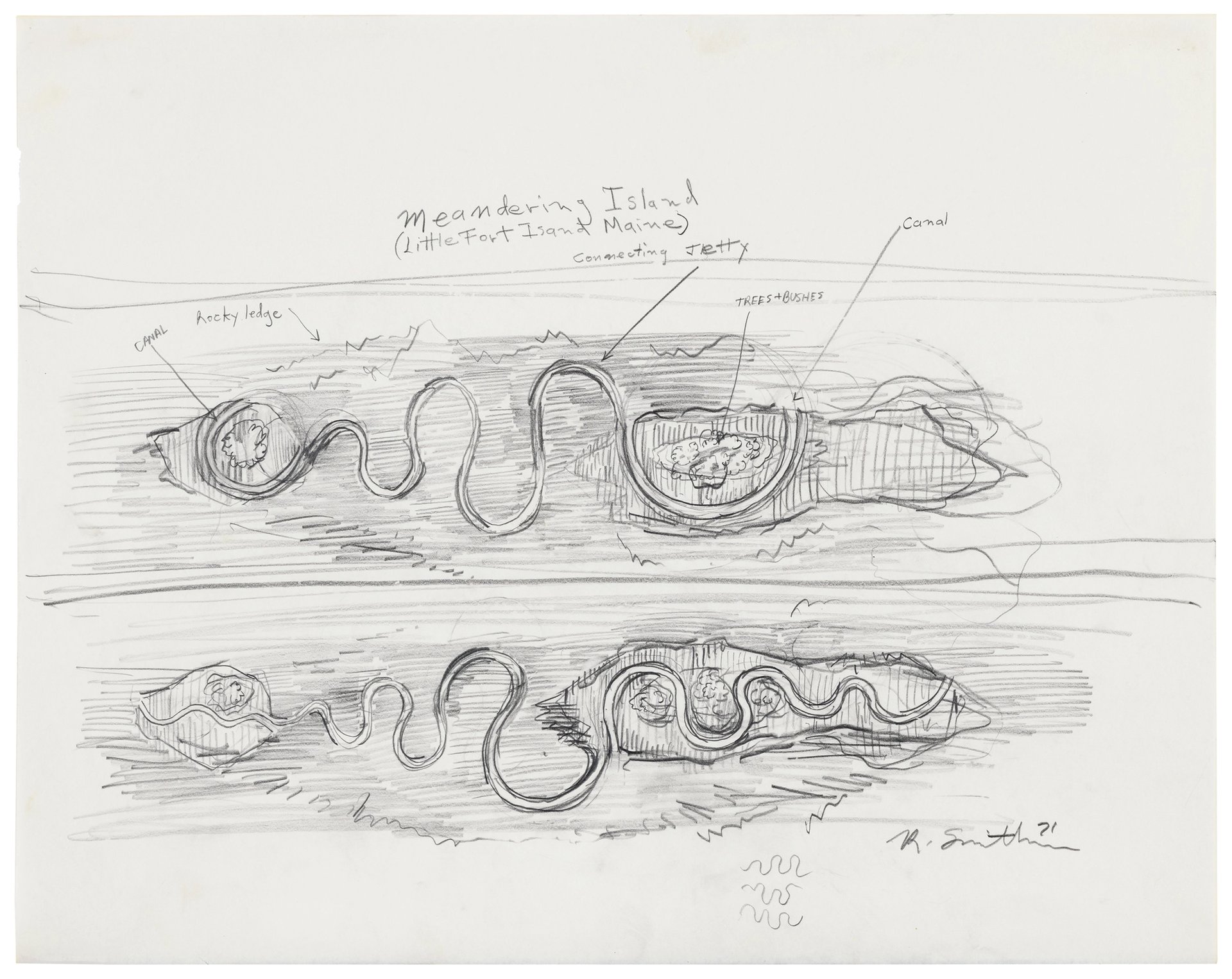

Before visiting Little Fort Island just off the coast of Harrington, Maine, which they were able to buy cheaply, Smithson made two drawings of earthworks snaking the length of the landscape. But he abandoned the concept after actually going to the site in 1972.

Robert Smithson, Meandering Island (Little Fort Island Maine) (1971) ©Holt/Smithson Foundation, Licensed by VAGA at ARS, New York

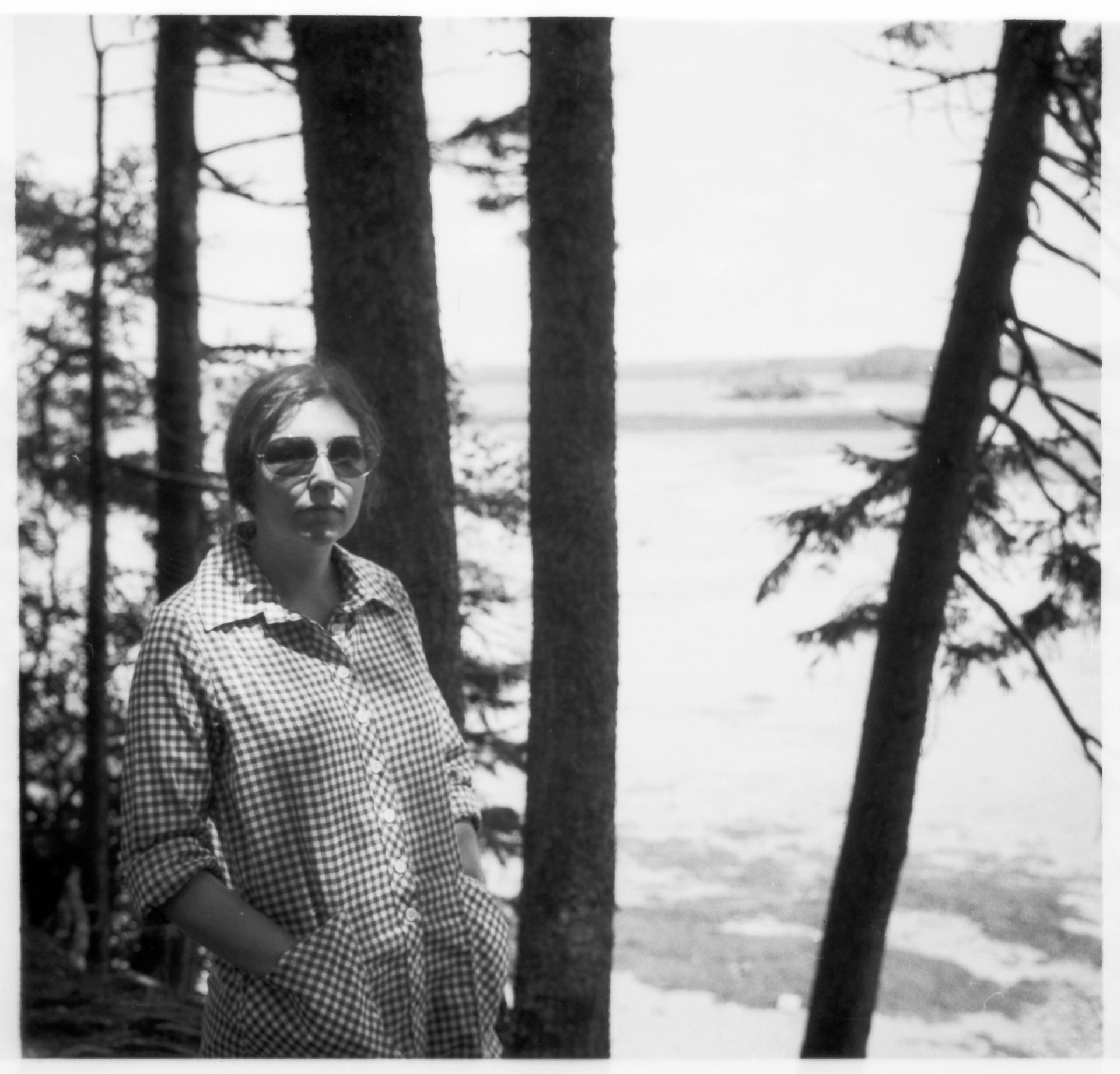

“Immediately, he was struck by how beautiful it was and decided it wasn’t right for him to make a piece on,” says Le Feuvre, explaining that he liked to work with properties that had traces of human existence. With the deed to the island eventually left in Holt's will to the foundation, “we really wanted to take on the idea of speculative thinking of a place imagined but not visited,” she adds.

Working with a panel of international nominators, the foundation came up with an initial list of 120 artists and then narrowed it to the five selected. Each received an email out of the blue, with the proposition to consider the island over the next three years and dream up a concept that could exist on-site or off-site and in any media. If the proposal could be realised, the foundation would work to find partners to bring it to fruition. All five quickly said yes.

Nancy Holt near Little Fort Island, Maine (1972) Photograph: Robert Smithson ©Holt/Smithson Foundation, Licensed by VAGA at ARS, New York

“Most institutions don't have the time or resources to say to an artist: ‘Just research for a few years’,” says Le Feuvre, who eventually would like to exhibit all the proposals for “The Island Project: Point of Departure”, to show the range of different positions.

The inter-generational group—ranging in ages from Jonas, 84, who knew Holt and Smithson personally, to Green, 62, to Hopinka, 36—all have acknowledged the influence of Holt and Smithson on their practices as well as an interest in islands in some way.

The invited artists, from left: Sky Hopinka, Oscar Santillán, Tacita Dean, Renée Green and Joan Jonas

Dean, 55, whose 1998 audio work Trying to Find the Spiral Jetty directly references Smithson, is excited to visit the island once pandemic restrictions are lifted. “I like to know that there is this call to go to somewhere and also to travel in their footsteps,” she says. “I'm someone who works from experience and who likes following traces.”

Santillán, 40, in turn, asked the foundation what it would mean if he never actually went to the island, and he has requested a geological survey. “The notion of fictional places has been part of my practice,” says Santillán, who is assessing whether to let the site remain a “phantom island” in his imagination.

After opening the foundation's original email, Santillán's first thought was it was spam. His second thought, he recalls, was: “If this is real, it's the most wonderful invitation I could get as an artist.”