The Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna has discovered an ancient Egyptian scroll hidden inside a vessel containing a mummified ibis. In the lengthy text, which are business notes, the scribe names three men he accuses of theft. It dates from around 1100BC.

The rolled-up papyrus, wrapped in two layers of linen, was found when conservators were examining their animal mummies before moving them to a new storage depot in Himberg, outside the Austrian capital.

A crucial question is whether the papyrus was inserted in the clay cone-shaped vessel in antiquity or in modern times, when it was in the Miramar collection, owned by Emperor Maximilian of Mexico. The monarch acquired the object in Egypt in the mid-19th century. After his execution in 1867, Maximilian’s collection passed to his Habsburg brother, the Austrian Emperor Franz Joseph, and in 1883 it entered the Kunsthistorisches Museum.

Samples of the mummy’s linen covering and the two pieces of fabric used to wrap the scroll were sent for radiocarbon testing to determine the dating. The results showed that the scroll’s inner wrapping dates from around 1100BC, while the other fabrics are both much younger, around 400BC.

Regina Hölzl, the director of the museum’s Egyptian and Near Eastern collection, believes that “it is very likely that the scroll, which has survived in a safe place for several centuries, was deliberately inserted into the ibis cone in Ptolemaic times to raise the votive value of the mummy”.

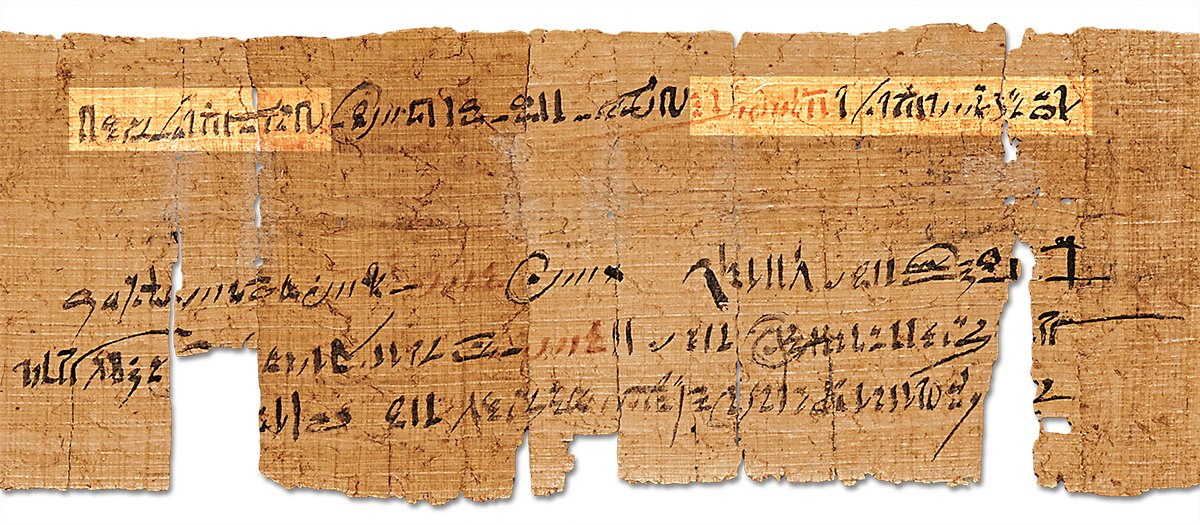

Conservators placed the brittle papyrus in a humid chamber to restore its flexibility before it was treated with cellulose and smoothed with a suction table and weights KHM-Museumsverband

Rolled-up papyri are now a rare find. Conservators had to devise a special method to flatten the text. Because of its brittle condition, it was first treated in a humid chamber to restore the flexibility of the fibres. The papyrus was then treated with cellulose and smoothed with the aid of a suction table and weights.

The text was in hieratic cursive writing used for everyday documents. Robert Demarée of the University of Leiden, who deciphered it, was able to confirm that the scroll was written by the scribe Thutmose who records his name in the document. His handwriting is also known from examples in a number of museums including London’s British Museum, the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford and the Egyptian Museum in Turin.

The text is the equivalent of a notebook or cashbook in which Thutmose recorded his business transactions. He listed supplies that he used, such as copper, turquoise and lapis lazuli, and objects he bought, including amulets and jewellery. Thutmose also recorded that some clothing was stolen from his house and he named the suspected thieves: Amenhotep son of Qenna, Nesamenope son of Hay, and Pentawemet.

The Vienna discovery suggests that other ibis mummies could hold papyri. Sealed ibis mummies are now rarely opened, but with x-rays, conservators can examine the cones without damaging them and then decide to open those which appear to include texts.

Ibis mummies survive in enormous quantities as the bird was the sacred creature of the god Thoth. They were votive objects brought to temples by tens of thousands of worshippers every year. It is estimated that underground vaults at two sites alone— in Saqqara (outside Cairo) and Tuna el-Gebel (on the Nile in Middle Egypt)—could contain up to five million of these types of mummies.

The Forgotten Papyrus, an exhibition telling the story of the discovery, is due to open at Vienna’s Kunsthistorisches Museum from 8 May to 16 October. Hölzl says that she “really hopes that we will find other examples of written documents with animal mummies, which would confirm our hypothesis that the papyrus scroll was placed inside the Vienna ibis cone in antiquity”.