Economic reports released in New York and Los Angeles this week reveal the dire impact of the coronavirus pandemic on arts employment in the US. On Thursday, the Otis College of Art and Design released its annual report on the creative economy in California, finding that every single sector saw substantial losses throughout the year, with over 175,000 jobs gone across the state in the past year, including nearly a quarter of the cultural workforce in Los Angeles. While in New York, a report from the state Comptroller’s Office found that employment in the creative fields had fallen by 66% in the past year.

According to the Otis report, between February and December of 2020, 13.3% of jobs in the creative sector were lost throughout the state, mainly from the art hub in Los Angeles, where nearly 110,000 jobs have been cut, or 23.5% of the workforce. Throughout the state, fine and performing arts saw nearly 16,000 jobs lost, entertainment and digital media saw over 128,000, the fashion industry saw nearly 23,000, and creative goods and products saw nearly 6,000.

“We would be having a very different conversation if the federal government hadn't instituted the CARES act, including the expanded unemployment and the opportunity for self-employed contractors to take part in that unemployment, as many of the sectors in the report have large contract workforces,” says Adam Fowler, the director of research at Beacon Economics and the author of the report. “We’re doing better than I would have predicted, but relief efforts are like treading water and we're just idling by until the public health crisis is under control. So the question for California is how to make a push towards both financial support and regulatory support in public sector policy to incentivise recovery.”

Fowler adds that “it’s still an open question in terms of who’s going to survive and who’s not” for both artists and organisations. “There is no recovery plan for the performing arts, for example,” he says. “We’ve all been tuned in day by day regarding what the restaurants will do, but the restaurants have a powerful lobbying organisation that keeps their needs at the forefront of the conversation, whereas guidelines don’t yet exist regarding how a dance company can reopen with limited occupancy, for example.”

Smaller groups and individual practitioners are “going to need time to build a strategy if there’s going to be an extended period where their business model has to change,” Fowler adds, noting that it would be more helpful if relief funding were pinned to statistics about unemployment and public health, rather than expiring at relatively arbitrary dates.

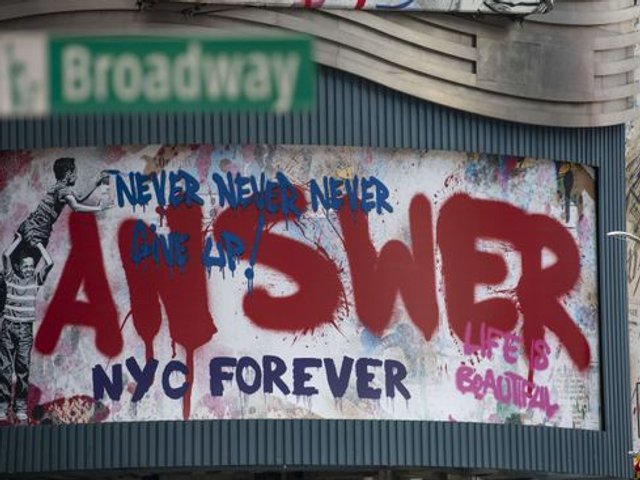

“We don’t want a recovery that doesn't include the arts,'' Fowler says. “What a depressing thought that we could come back to an economy that doesn’t have the interesting art, theater, and cultural assets that make our cities what they are. We’ve got to really take that seriously, because many of those business models were on the razor’s edge even before the pandemic.”

A further study by Californians for the Arts noted that, of the roughly 1,000 creative workers it surveyed, 88% of respondents confirmed that they had lost income or other arts-related revenue as a result of the pandemic. And 43% of respondents said they were unsure whether they would be able to continue to make a living in their chosen field moving forwards.

And in New York, a report from the state Comptroller’s Office detailed that, as of December 2020, employment in the creative industry had declined by 66% from the year before. According to the report, New York City was home to 93,500 jobs in arts, entertainment and recreation with an average salary of $79,300, but as of December, two thirds of these jobs have been lost. “Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, the level of employment, the number of establishments and total wages in the arts, entertainment and recreation sector had each expanded significantly over the past decade, growing at a much faster rate than for all sectors citywide,” the report says, adding that the city’s identity “as a cultural powerhouse” served as a magnet for workers and businesses “making the sector vital to the City’s economy”.

“Direct relief from the federal government, and state and local programs to create safe venues for artists and entertainers are steps in the right direction,” said New York State Comptroller Thomas DiNapoli in a statement, “but more help is needed to keep the lights on.”