Day’s End, a monumental, permanent work of public art by David Hammons on Hudson River Park, is now completed after seven years of planning, fundraising, impact studies, and community feedback, and will be officially unveiled on 16 May. The 325ft-long sculpture made of brushed steel poles recreates the outline of a former warehouse that once stood on Pier 52 off Gansevoort Street, across from the Whitney Museum of American art, which funded the project.

Taking its name from an earlier work on the pier by the artist Gordon-Matta-Clark, who surreptitiously carved out sections of the abandoned building as an architectural intervention, Day’s End is a sort of ghostly memorial to the site’s artistic and social history. “It’s enigmatic in a really nice way, in that it causes you to pause for a second and reflect, which is the whole idea,” says the Whitney’s director Adam Weinberg. “It’s like, ‘What is this? And why is it here?’”

“Part of the piece’s brilliance is that—because there’s no floor, no ceilings, no walls, it’s totally, totally open—it is the container of everything,” Weinberg adds. “You can’t photograph it without having something else in it. So it becomes the container for the trees, for the cityscape behind it, for the water. It basically—in true David Hammons fashion—is the most democratic of all works, because it’s not about itself as much as it’s about everything else it captures.”

Hammons’s Day’s End is located in Hudson River Park on the Gansevoort Peninsula Courtesy of Whitney Museum of American Art

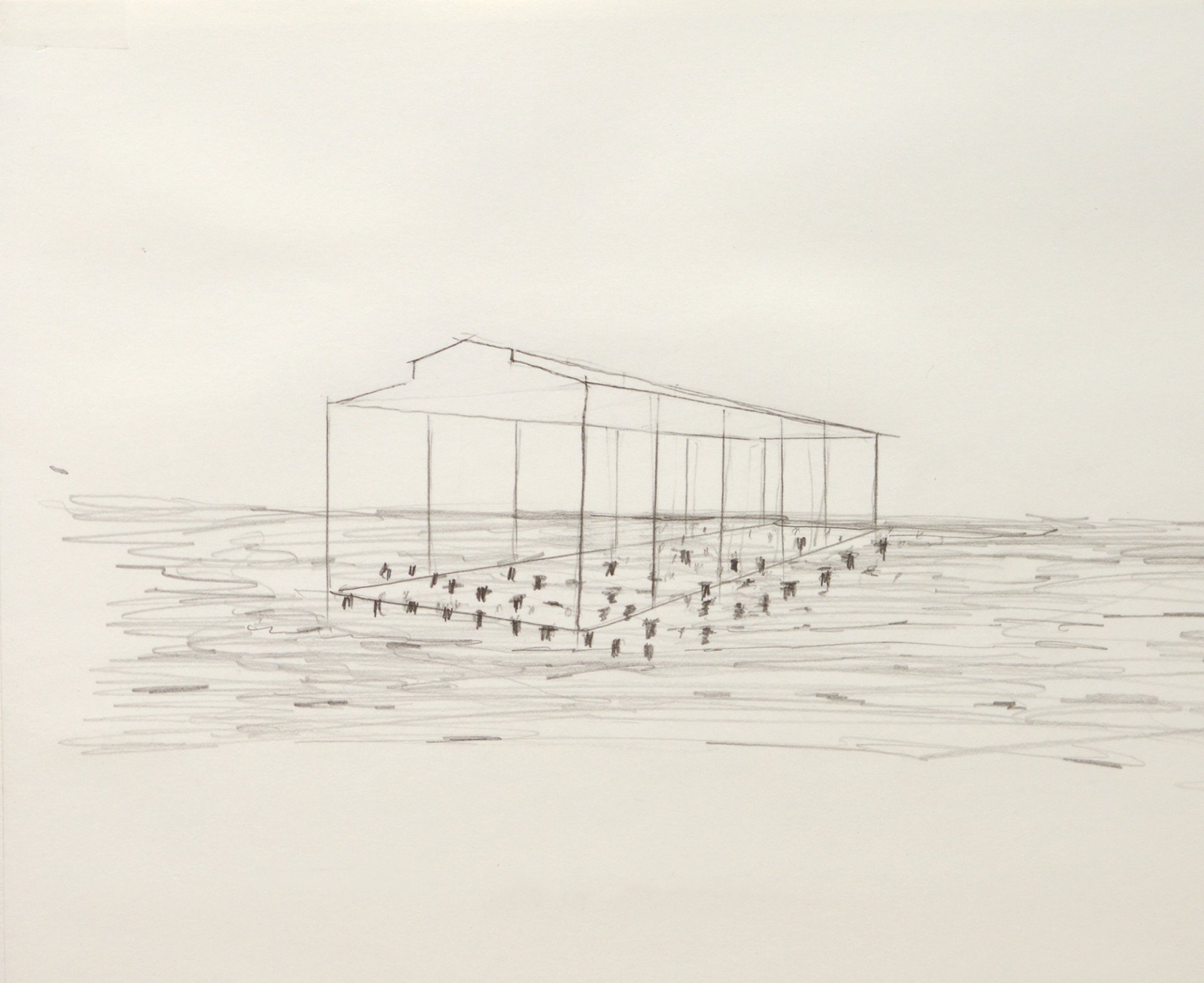

The project started as a sketch Hammons sent to the Whitney after visiting its newly opened building in the Meatpacking District and looking out from one of the gallery windows across the river. But completing the $17m sculpture, part of a $70m regeneration of a former sanitation site into a public greenspace, involved government planning, community organising and a lot of complicated engineering. “I had no idea what it would entail,” Weinberg says. “And, like most ambitious things I end up doing, if I fully knew what I was getting myself in for, I might not necessarily do them because it literally took, as you could see now, seven years from inception to realise it.”

David Hammons, Sketch for Day’s End

The groundbreaking for the piece took place in September 2019 and it was originally due to be finished last autumn, but the pandemic caused delays in production. Fabrication was done in five countries, Weinberg says, including Italy, Brazil and Canada, where outbreaks of the coronavirus “did slow things down”.

Installation of the work started earlier month as spring weather and progressed smoothly, however, with its completion announced today ahead of schedule. “In a way, I feel very fortunate, because what could be better than to have Day’s End be a part of the reopening of New York,” Weinberg says.

Installation of David Hammons's Day's End on Hudson River Park Photo: Timothy Schenck

The public opening of the project will be celebrated on 16 May with a Community Day of free family workshops (timed tickets will be needed), open admission to the museum and its exhibition, and other events. And as part of the education programming, the Whitney is launching its first podcast on 14 May, Artists Among Us, with a five-part series dedicated to Day's End, which explores Hammons's and Matta-Clark's work and the social history of the Meatpacking District. Narrated by the artist Carrie Mae Weems, the series will include interviews with ecologists, historians, artists, sociologists, LGBTQ speakers and Indigenous leaders.

"The idea was to really take this sculpture as a jumping off point or a portal through which to understand this really remarkable and yet very small piece of land in New York City, which has had such radical transformation over the last 400-plus years," says Tania Ketenjian, the co-founder of Sound Made Public, which produced the podcast in collaboration with the Whitney. "And then there's what happens when you create a work like Day's End, that stands very strongly on its own as a piece of art, but also is paying homage in a certain way."

David Hammons at the groundbreaking for Day’s End, hosted by the Whitney Museum of American Art, 16 September 2019

And while the Whitney has raised all the funding for the work—with $4.3m coming from New York City's culture budget, and the rest from private donors—and is now organising a maintenance plan and support for its long-term care, Day’s End will not be part of the museum’s collection. “Whether we physically own the piece that’s across the street from us in perpetuity or not is really beside the point,” Weinberg says. “The point is, we are guardians of our visual culture, and this one happens to be next door to us. We’re very lucky.”

David Hammons, Day’s End (2014-21) © David Hammons. Photo: Timothy Schenck