Mainland China’s nationwide lockdown to prevent the spread of the novel coronavirus, Covid-19, is reverberating around the art world in a way that is outstripping the country’s last major epidemic, Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (Sars) in 2002 to 2003.

Hubei Province and its capital Wuhan, where the virus likely originated, have borne 83% of the 78,000 confirmed cases of Covid-19 at the time of publication, as well as most of its 2,600 fatalities, more than twice the number who died from Sars. Wuhan’s lively art scene is as overwhelmed as the rest of the city, claiming the lives of two artists: the painter and professor Liu Shouxiang, born 1958, and another whose family asked they not be named. Another, the painter Zhang Wei, is reportedly infected and in critical condition.

Cancellation of the region’s marquee art fair, Art Basel in Hong Kong (ABHK), was announced in early February; the fair could weather ongoing democracy protests, but not a ban on individual visitors from the crucial mainland market. The fair’s cancellation, though, pales in comparison with the global, long-term impact of sequestering Asia’s economic giant and the world’s second largest economy indefinitely. China accounted for 4% of the global economy at the time of Sars; now it is 16%. Millions of factories, restaurants and shops are closed indefinitely along with museums and galleries. Asia’s economy, already navigating a slowdown and a trade war with the US, now faces travel bans and disrupted supply chains. Even assuming there are no further infection clusters, as in Wuhan, there are murmurs of recession.

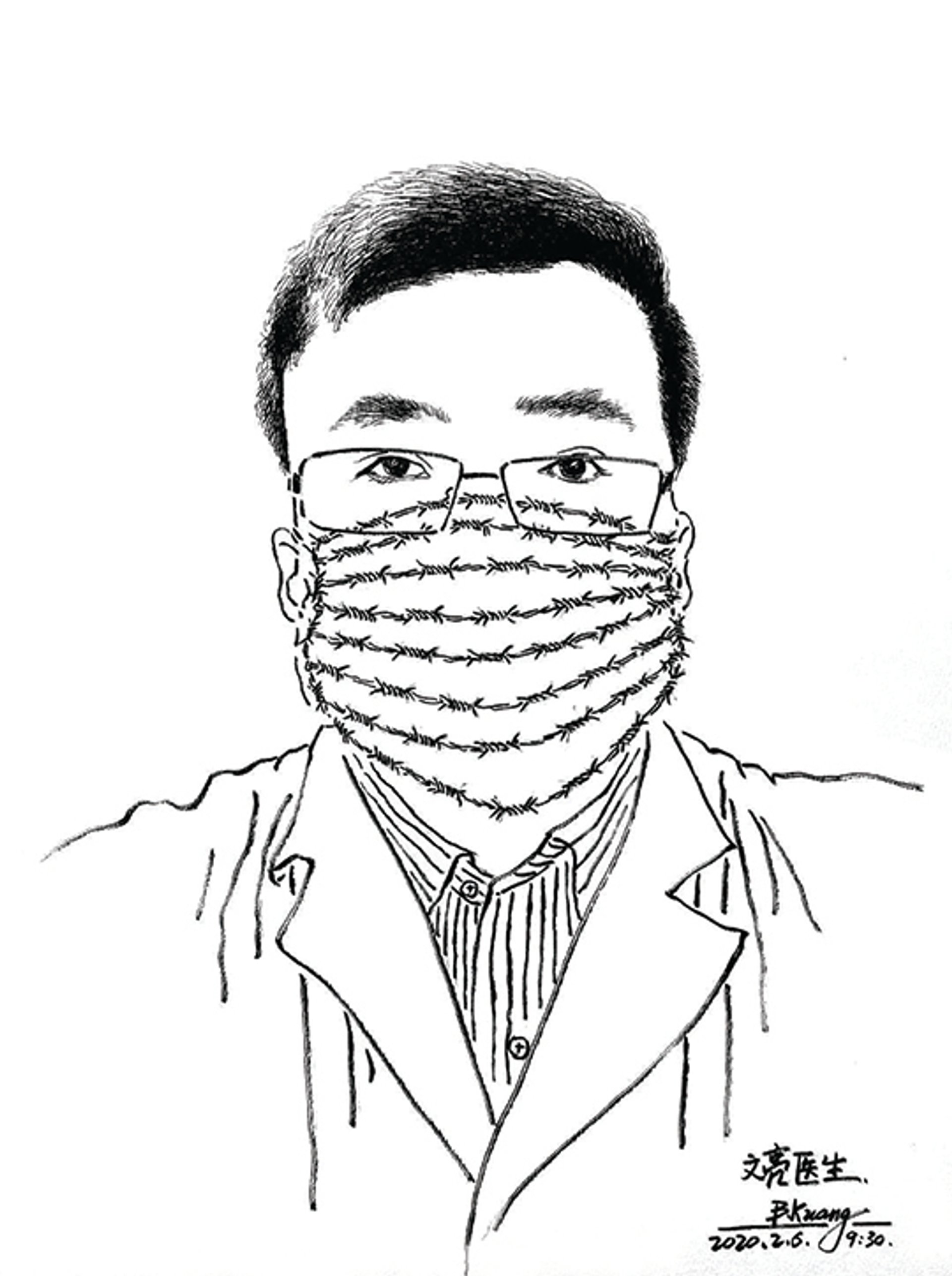

Kuang Biao's commemorative portrait of Li Wenliang , the doctor who died of the Covid-19 virus in Wuhan © Kuang Biao

“What I consider crucial is the general mood of the art world. An active market attracts more collectors, clients and people, but if the general economy and the public mood is sluggish, so too is the art market,” says Henna Joo, the director of Arario Gallery, which has locations in Shanghai and the South Korean cities of Seoul and Cheonan. “The cancellation of ABHK provides a chance for many galleries to reconsider their business models. They can see how a year without ABHK affects their yearly performance. What they, and we, lose is a chance to meet the international new clients—but that will resume next year. This is a one-time phenomenon.”

Lorraine Kiang Malingue, the director and co-founder of Hong Kong and Shanghai’s Edouard Malingue Gallery, expects sales in Asia to take a hit for the quarter, with “small to medium-sized galleries who were meant to be participating in ABHK being affected most”. Malingue expects a range of creative coping strategies, with the focus more on “this tragedy hurting families [than] the tiny art market. It’s a time for reflection and to explore new ways of engaging with the public.”

China’s art scene now is radically different to the intimate, underground upstart of 2003 under Sars. “It was dreamlike and surreal. There was no social media, we had mobile phones then but not smartphones, and everyone in the art world was working independently,” says Karen Smith, a historian and curator based in China since 1992, who now is an adviser at the Shanghai Center of Photography and the executive director of the Xi’an OCAT museum.

Instead, Smith recalls, it was months into the Sars crisis “before we really knew about it, and it was great weather with no quarantine. We cooked a lot, had dinner parties. It is the opposite now… the contrast is the level of information people have”—verified or not. “Artists got together, and communities could do something; there has been a disintegration of that spirit. [In several cities] people are even locked into their apartments.”

Bouncing back

Smith also describes the enforced slowdown after a decade of relentless expansion as a silver lining for China’s art world. She says Beijing bounced back quickly from the aftermath of Sars. In the year after the crisis ended, delegations from the Tate in the UK, New York’s Museum of Modern Art and the Asia Society toured China’s recovering art scene. “By 2004, the energy was back,” she says. “People have very short memories. And things were gearing up for the [2008 Beijing] Olympics, [Guy] Ullens was getting ready to open [the Ullens Center for Contemporary Art], Hou Hanru’s Venice [Biennale] show happened, and there was lots of travel.”

It is too soon to say whether 2004’s buoyancy will be repeated in the coming years. One factor is that the Sars crisis took place in a different political climate. Media and artistic expression were much less restricted than they are under the current Chinese president Xi Jinping, who has been conspicuously absent from the public eye for most of the epidemic. The death last month from Covid-19 of Li Wenliang, the Hubei doctor who was detained and silenced after he identified the virus in December, sparked an outpouring of commemorative art and outraged grief from hundreds of millions of Chinese people. Criticism of the government’s handling of the outbreak has received intensified online censorship. Many low-level local authorities, even in areas with few Covid-19 cases, are instituting draconian controls of residents far beyond the official measures.

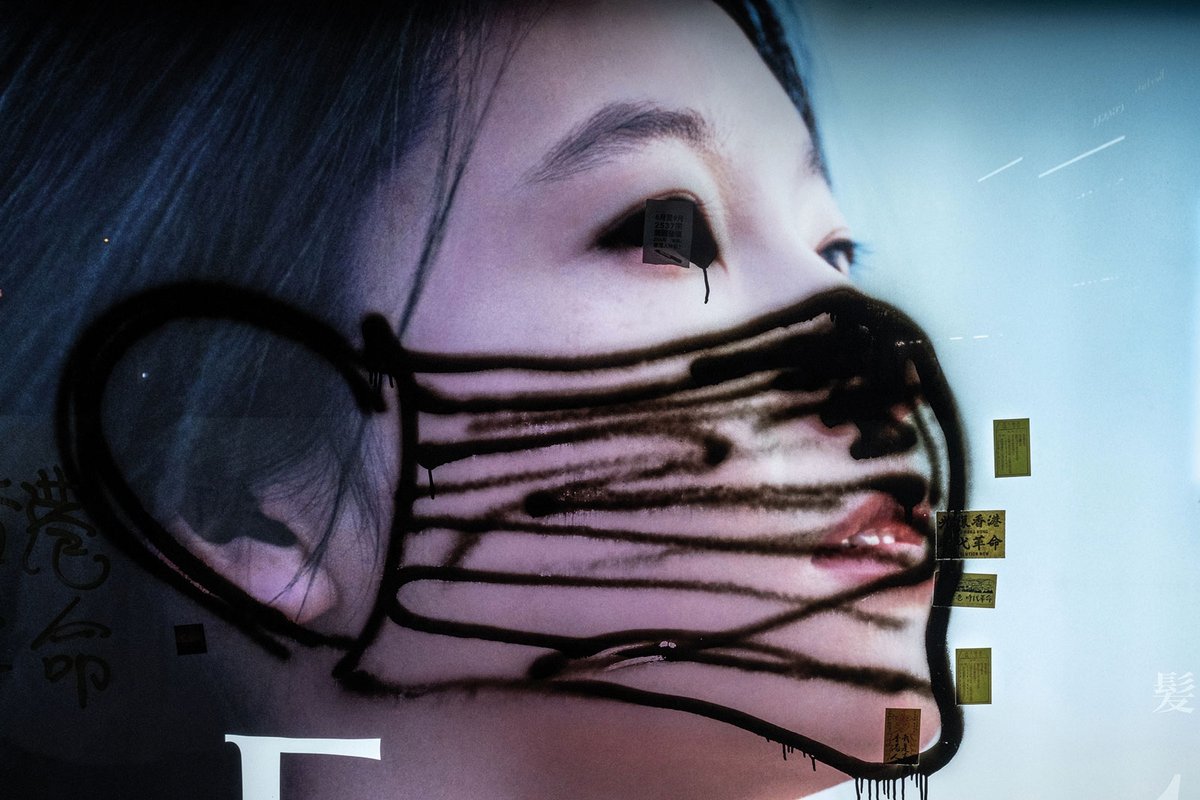

Meanwhile, fears over Covid-19 cases abroad have revived old racist scripts of Chinese people as backwards and diseased, with widespread reports of discrimination linked to the virus against ethnic East Asians. Malingue, however, doubts that will dent the global reception for Chinese and Asian art. “I believe the majority of people are sympathetic to the current situation and would hope for the best for Asia. As always, it will always get better. For those who have been aggressive against China and Hong Kong, they will just stay behind. This crisis will show who is friends with Hong Kong and China.”

• Read all of our coronavirus coverage here.