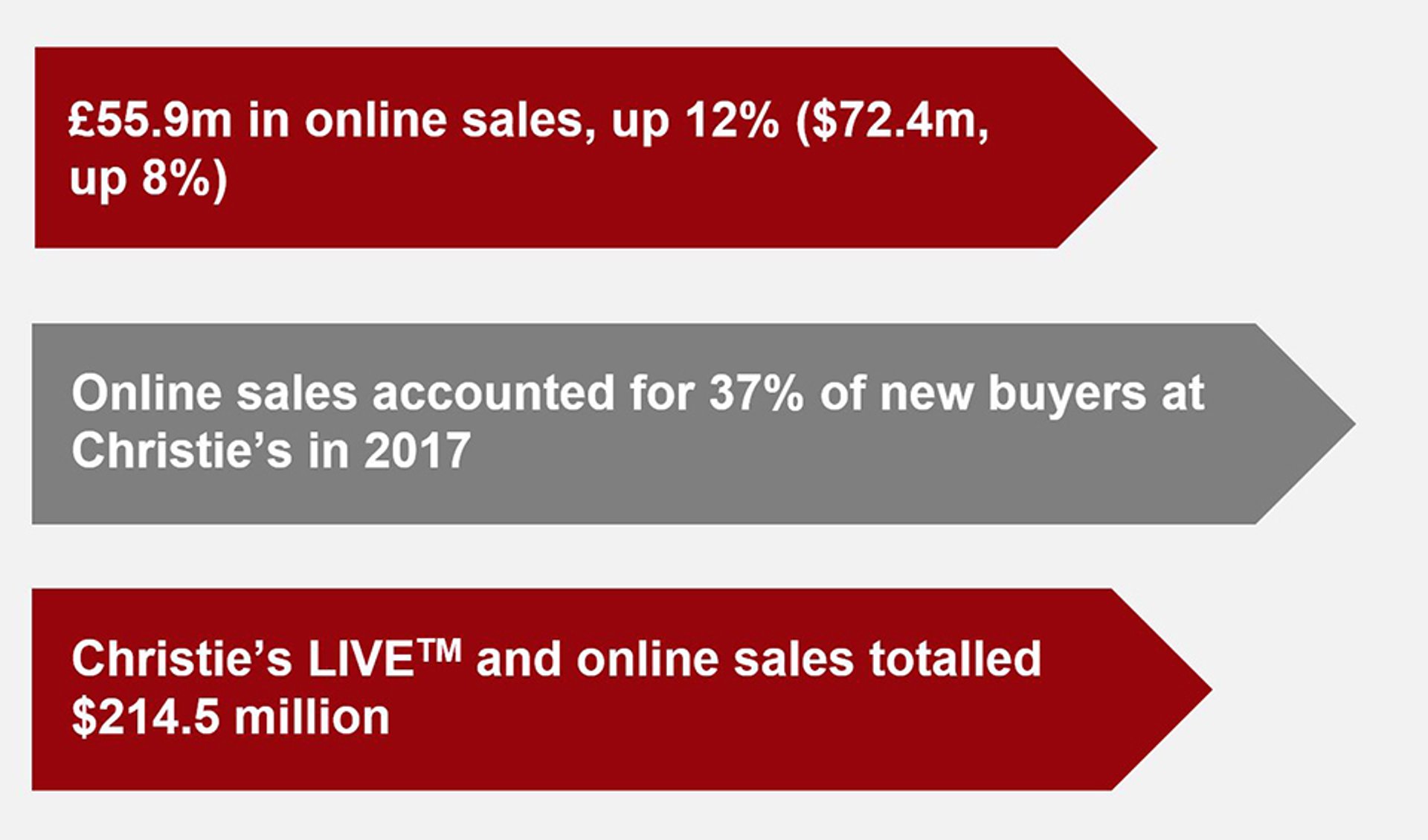

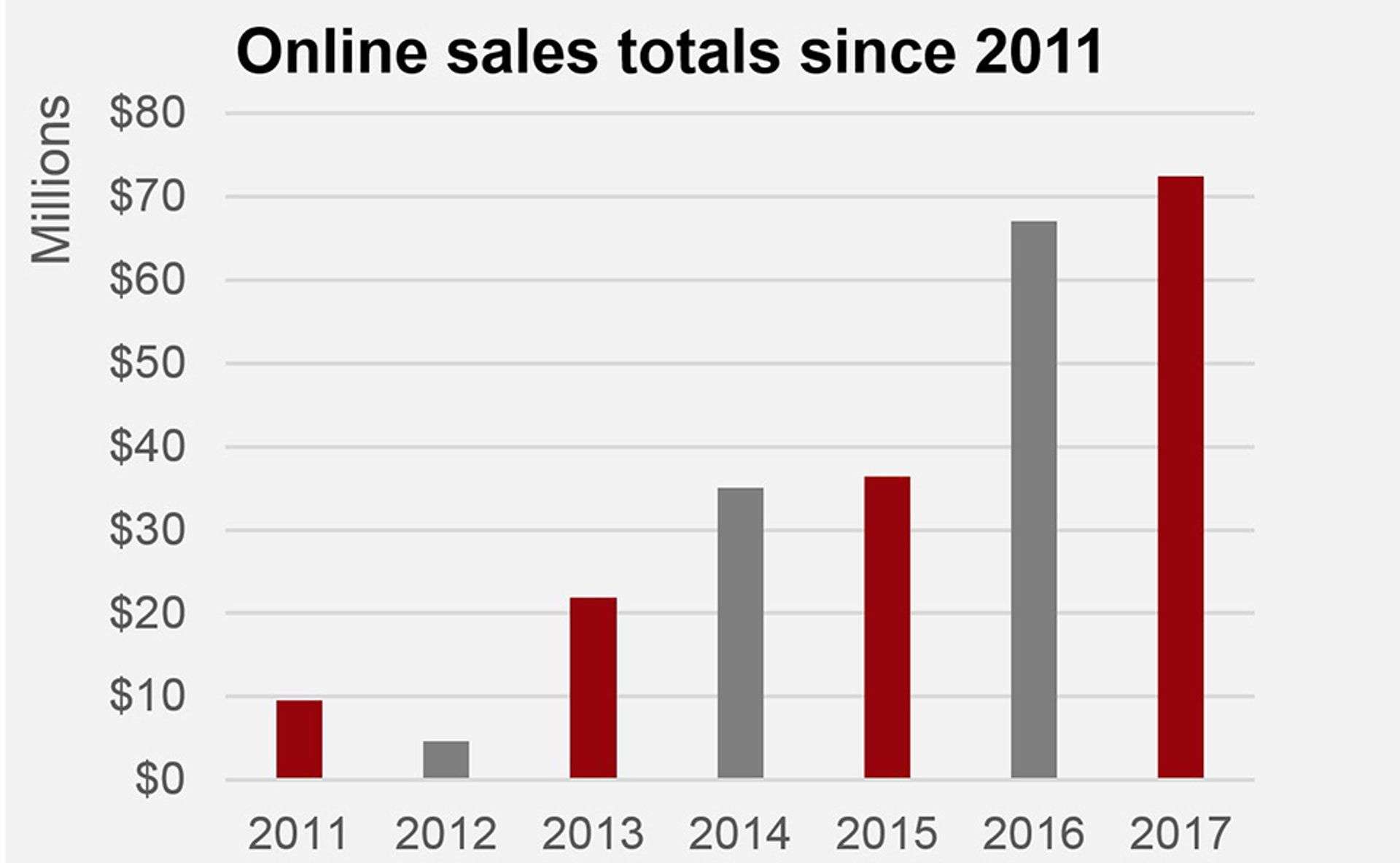

After a dip in 2016, Christie’s says its total global sales increased by 26% to £5.1bn (or $6.6bn, a 21% increase in US dollars) in 2017, helped in large part by the $450.3m Salvator Mundi by Leonardo da Vinci sold by the auction house in November. The bulk, predictably, came from auction sales, which contributed £4.6bn ($5.9bn), up 38% on 2016, with a 81% sell-through rate, while online sales added £55.9m, up 12% ($72.4m). However, private sales were down by 32%, at £472.4m ($611.8m).

Despite global economic and political uncertainty, 2017 was a strong year for the top end of the art market, with data-driven reports pegging the growth at 25% across auction houses. Jussi Pylkkänen, Christie’s global president, says the results were helped by low interest rates, which always aid the art world, but also notes: “There’s a comforting certainty in works of art: a Monet will always be a Monet, a Picasso will always be a Picasso. I’ve witnessed that consistently over the past decade.”

Christie's

Pylkkänen was surprised by the roughly even geographical split of the results: the Americas (32%), Europe and the Middle East (37%) and Asia (31%) each brought in around a third of sales. The number of Asian buyers who spent at least £1m increased by 63%, and Paris sales were up 49%. “I’ve never witnessed results so consistently good across the board, but we are not complacent”, he says. “To be honest, it is very unusual for us to have sold seven out of the ten most expensive works at auction, as happened last year.”

In all, 31% of buyers were new to Christie’s in 2017, of which the majority (37%) were brought in by online sales, an area that the firm—like its competitor Sotheby’s—sees as a key area of growth. Online sales (including both online-only sales and live bidding) reached £165.6m ($214.5m) last year, only slightly up from £161m ($217m) in 2016. Although confidence in remote buying has increased, Christie’s top prices for works sold on the internet in 2017 remain low compared with their physical salerooms—$324,500 in an online-only sale (for a Rolex Submariner 6538) and $1.57m for a lot won by an online bidder in a live auction for Alexander Calder’s Sans Titre.

Pylkkänen says: “Online totals might seem small compared to the Salvator Mundi, but that is where the future lies. The growth lies in the future scope of what we offer and the regularity of sales, not in individual prices. We have to make vendors in collectors' areas, like Picasso ceramics, confident that it’s sometimes a better way to sell than a traditional bricks-and-mortar auction.” Many such lower value, "collector" category sales would traditionally have been held at Christie’s secondary South Kensington saleroom, which the company controversially closed last summer. “We are comfortable that we made the right decision to close South Kensington”, Pylkkänen says.

Christie's

As for the 32% drop in private sales, Pylkkänen says it reflects confidence: “When you look at the sort of value top works were making at auction [in 2016]—such as the Bacon triptych and the Modigliani—I think it’s a conscious decision by vendors to go on the open market and make people compete. Only then will you get extraordinary prices.”

In 2018, Christie’s will concentrate efforts on online sales, Los Angeles (where it opened an exhibition space in April 2017) and Asia, “which remains critically important”, Pylkkänen says.

Sotheby’s will release its 2017 total sales, along with its fourth-quarter earnings, in late February.